Minseki registers, 1868-1945

The nation defined as demographic territory

By William Wetherall

First posted 1 June 2021

Last updated 23 July 2021

"Minseki" population registers

From Tokugawa to Meiji

•

1895 Minseki households and populations

•

1920 National census by kokuseki and minseki

•

1930 National census by minseki and kokuseki

"Minseki" as "subnationality"

Belonging to Naichi, Taiwan, Karafuto, and Chōsen as different legal territories of Japan

Commemorating Japan's 1920 census

3-volume commemorative publication

•

Jinmu and Meiji

•

1920 shokuminchi

•

540 kikajin

1853-1876 International Statistical Congresses

•

1872 International determinations

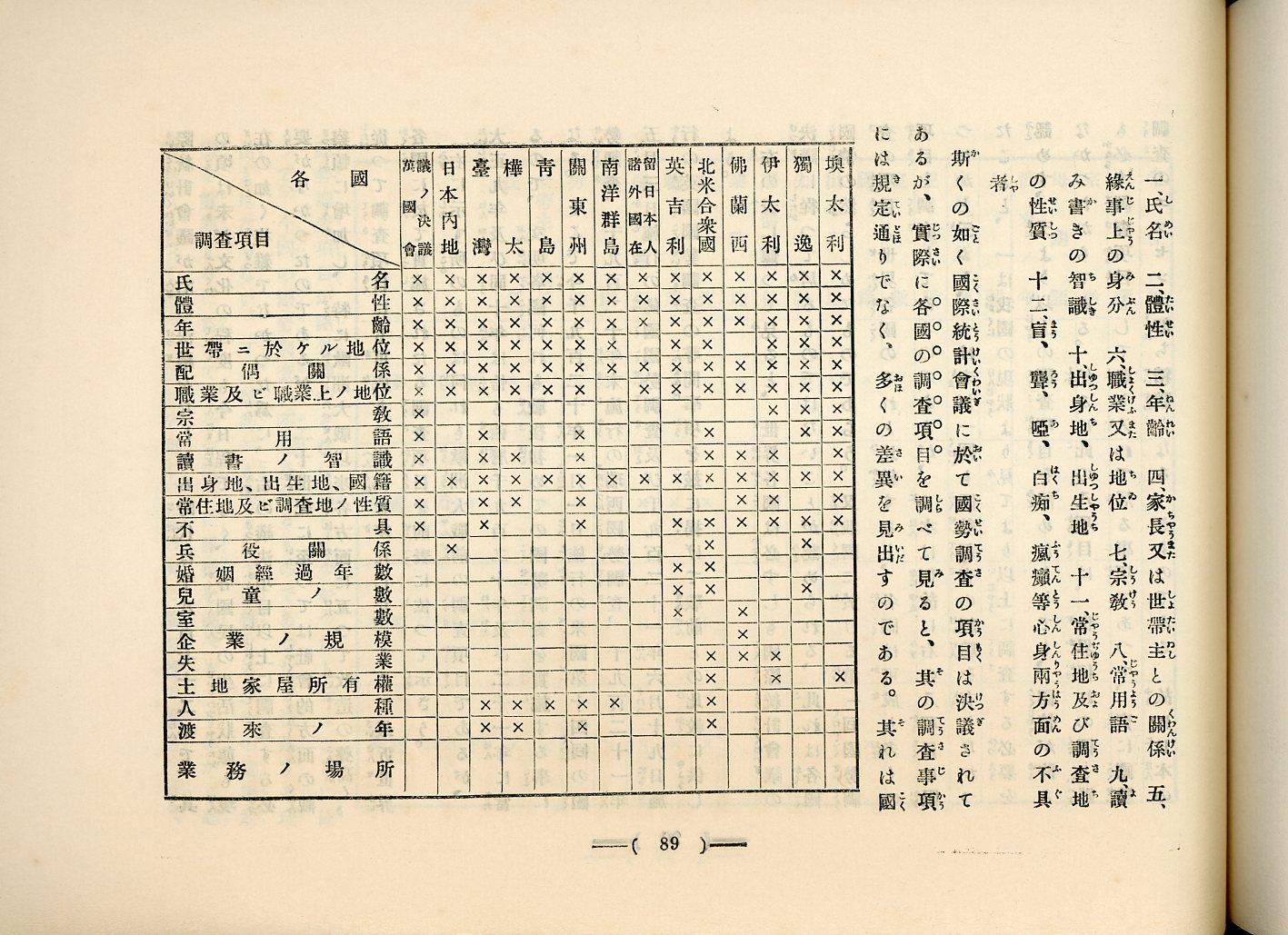

12 essential items

•

9 discretional items

1920 census enforcement order

Minseki & kokuseki on census forms

•

Commemorative postcards

•

Commemorative stamps

Sources

Related articles

1872 Family Register Law: Japan's first "law of the land"

The Interior: The legal cornerstone of the Empire of Japan

Belonging in Japan past and Present: Before and after "nationality" and "citizenship"

Affiliation and status in Korea: 1909 People's Register Law and enforcement regulations

Affiliation and status in Manchoukuo: 1940 Provisional People's Register Law and enforcement regulations

Minseki

Minseki in late Tokugawa and early Meiji"Minseki" as a term that probably means "jinmin koseki" can be found in Great Council of State records predating the promulgation of the Family Register Law in 1871.

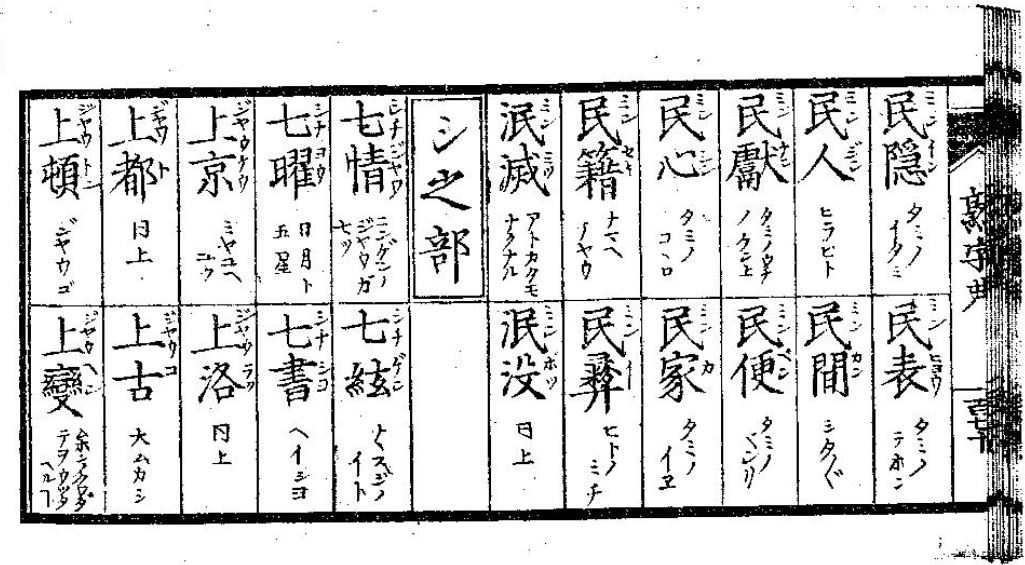

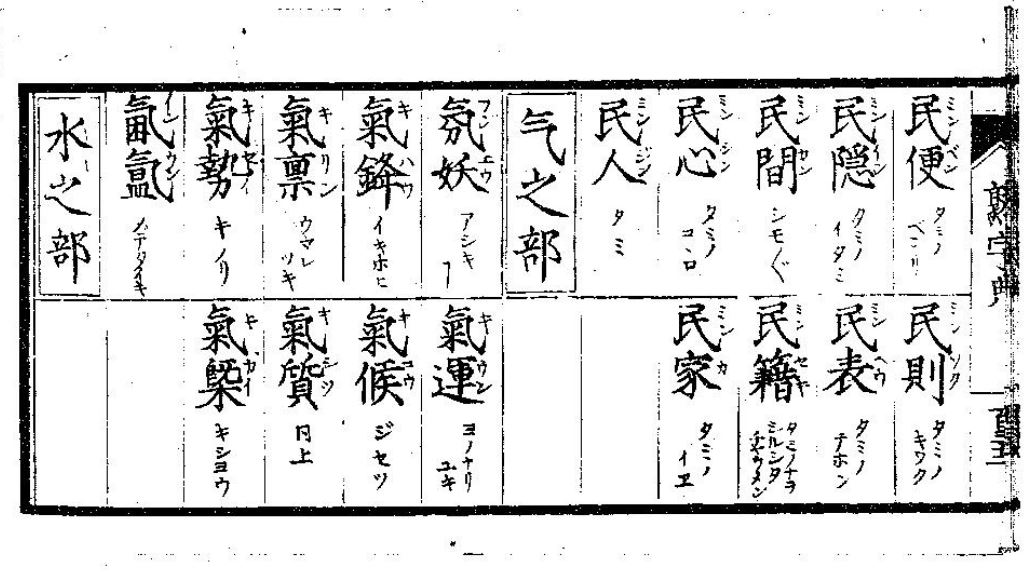

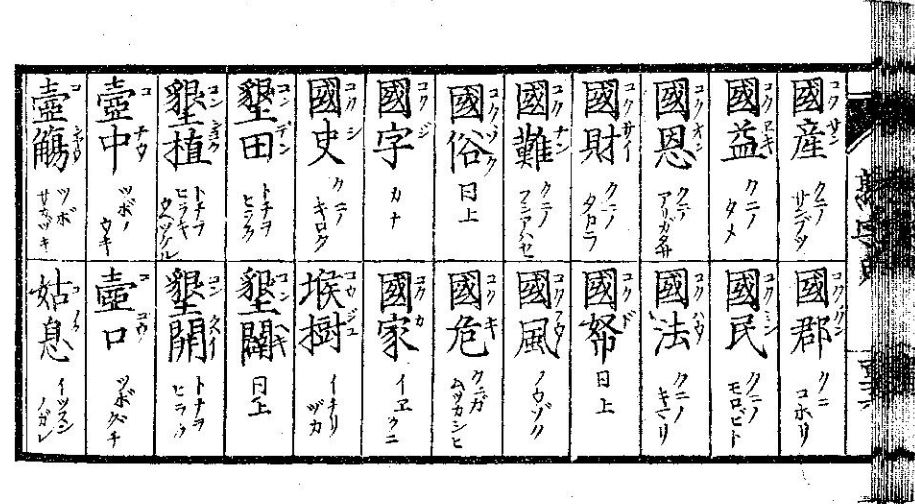

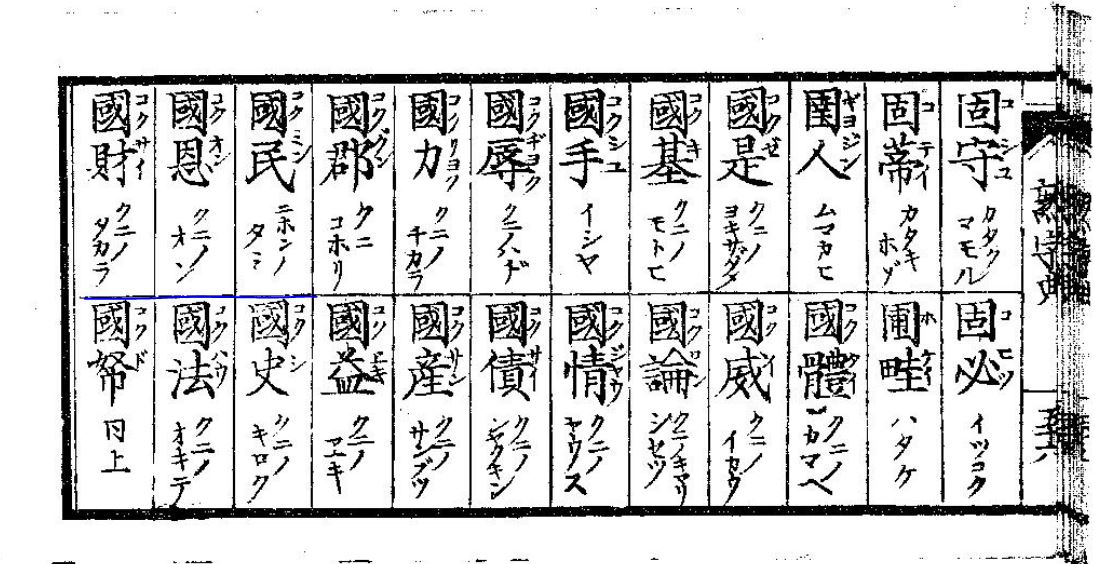

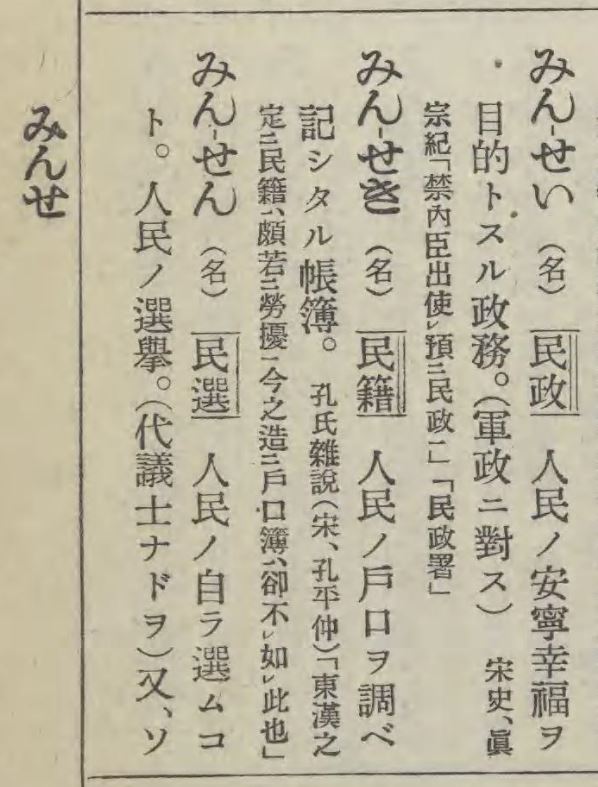

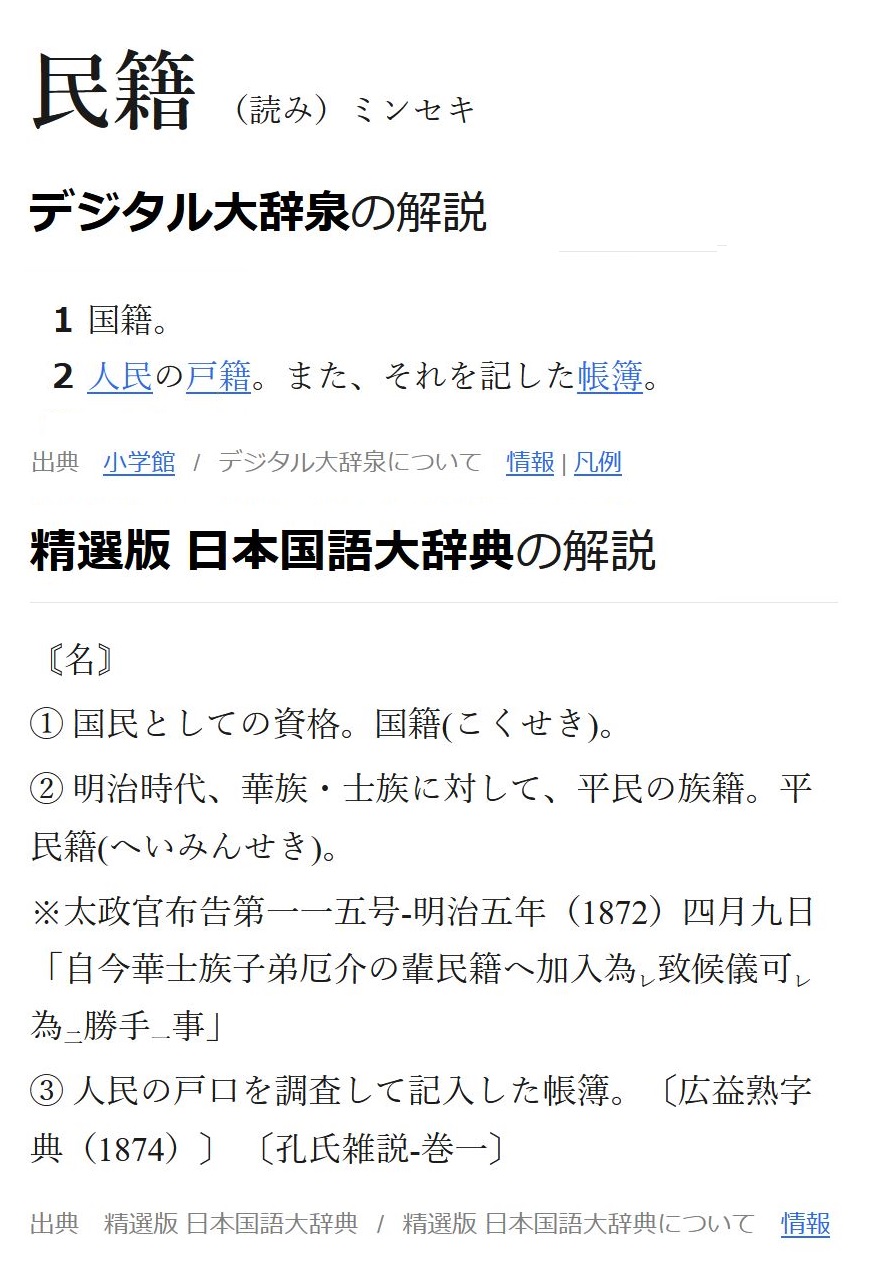

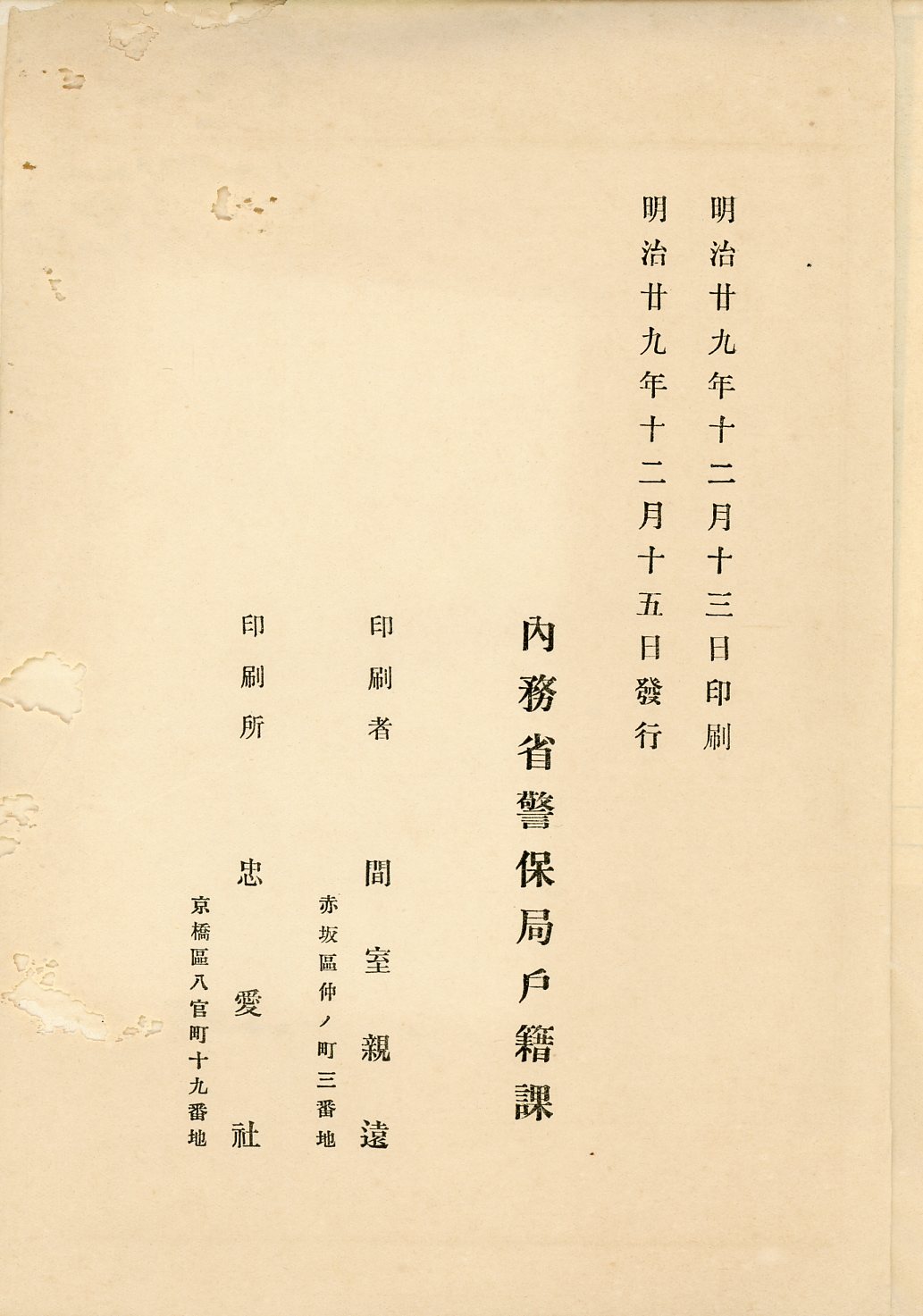

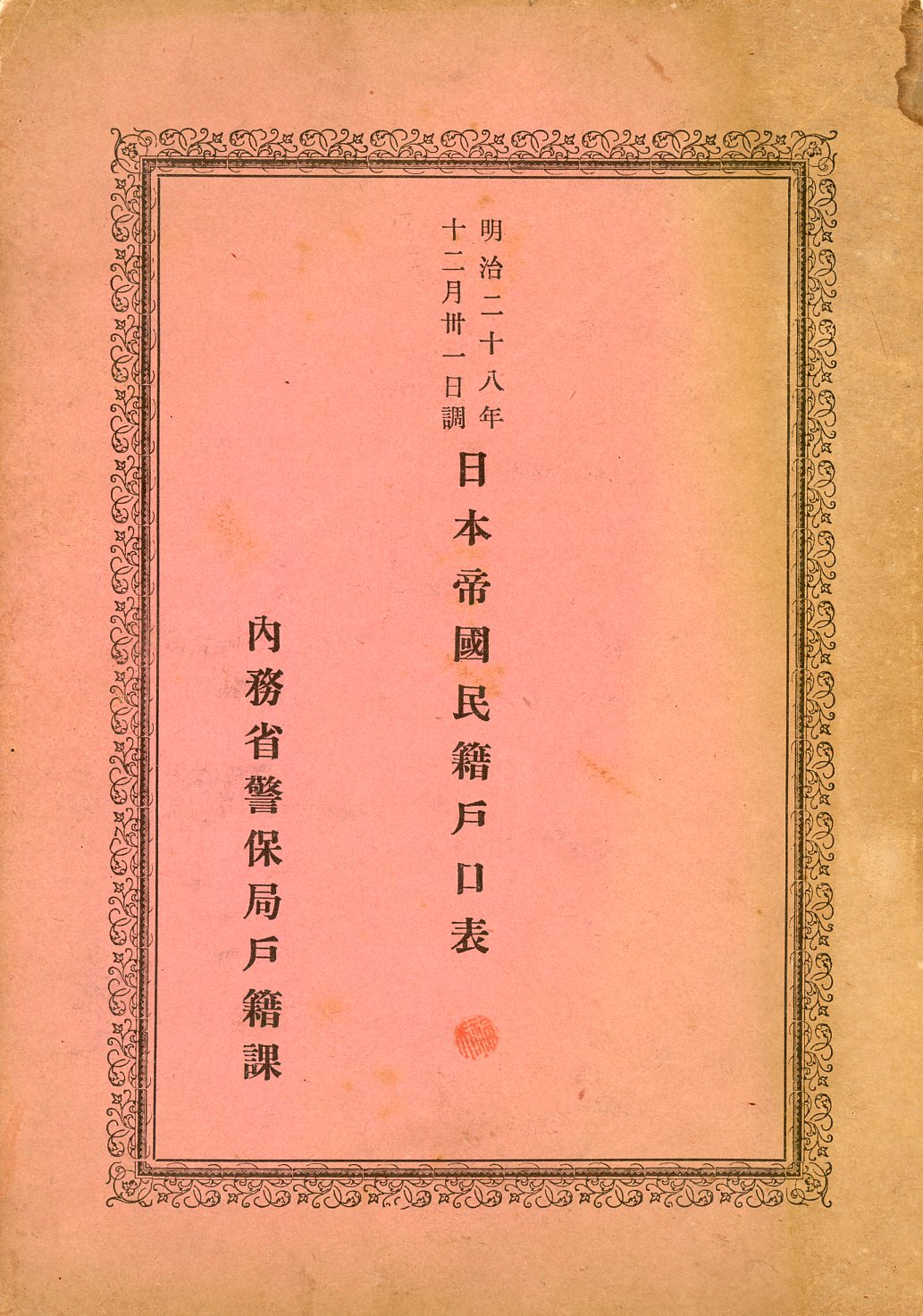

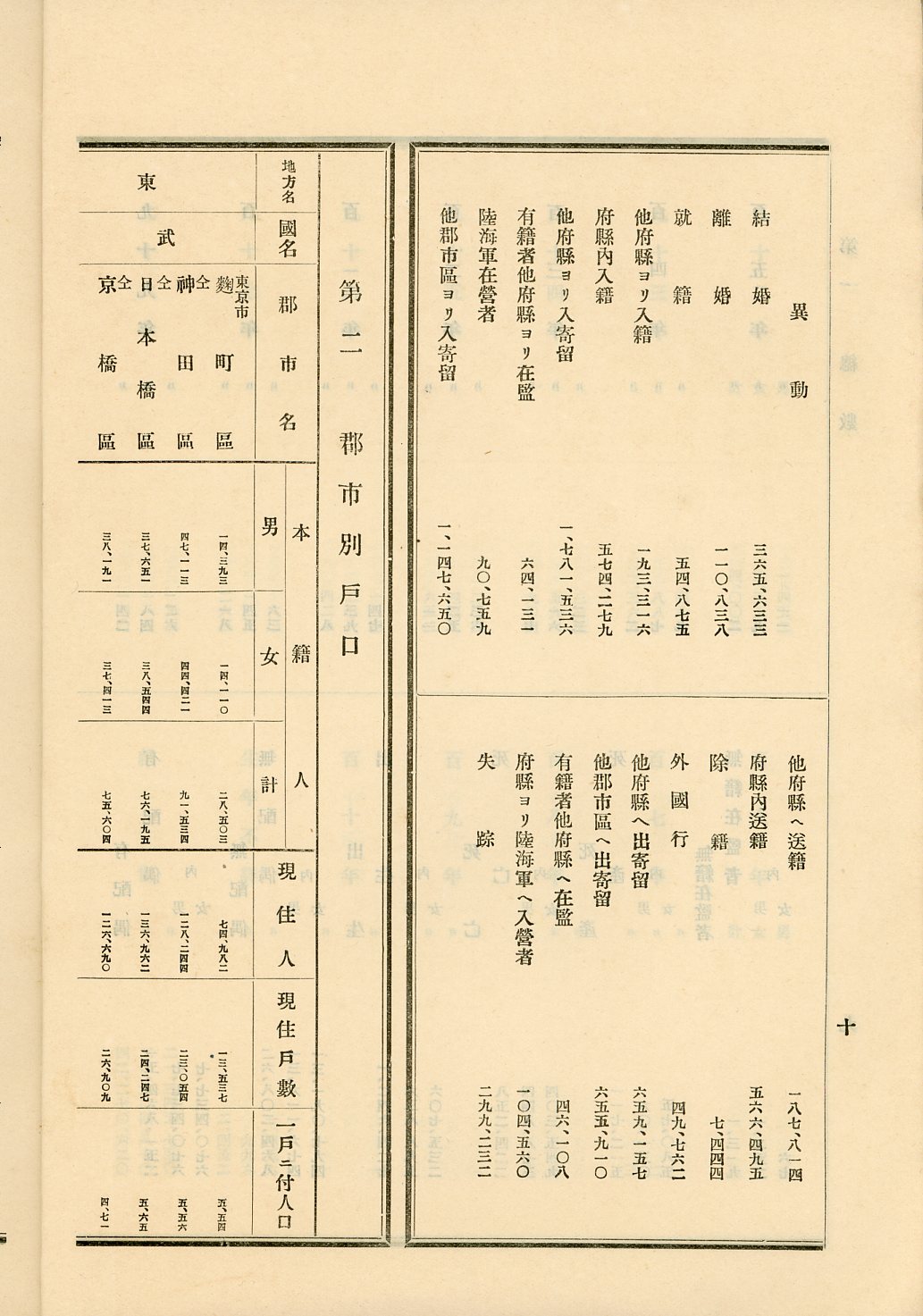

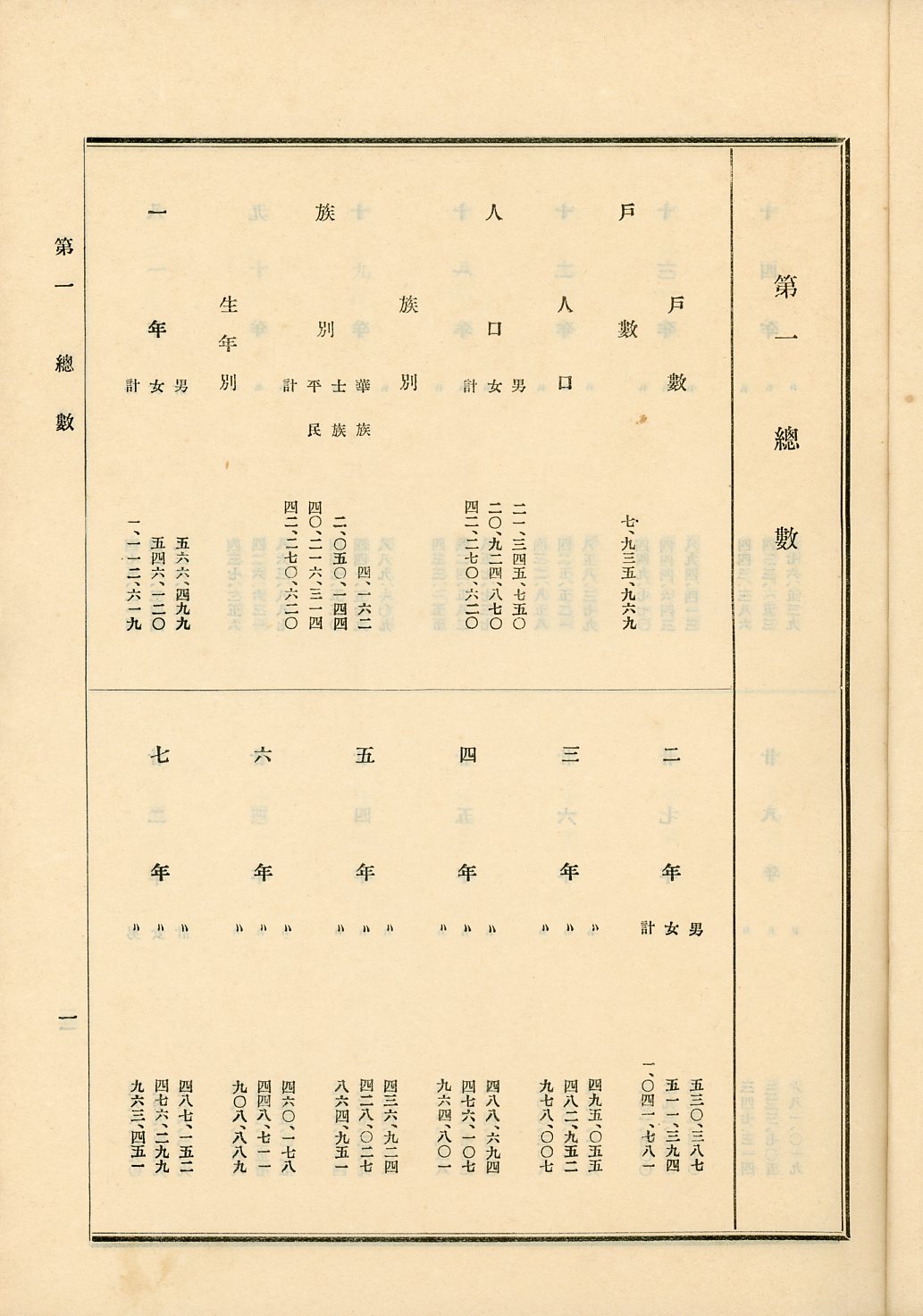

Minseki population registers"Minseki" as demographic territorial affiliationThe 1871 Family Register Law calls the registers in which people considered "jinmin" or "kokumin" or "shinmin" were to be enrolled as "koseki" (戸籍) -- meaning a "household" or "family" register. However, the term "minseki" (民籍) -- meaning an "affiliate register" -- was also used in Japan at the time to describe a population register. The term "minseki" can be seen in the notice of change of registration status that appears immediately before the text of the Family Register Law, as follows (see image above). 森岡縣士族小山田治六脱籍に付庶民に下シ民籍ニ編入 The distinction being made here is between registers for the pedigreed classes -- "nobility" (kazoku 華族) and [former samurai] "gentry" (shizoku 士族) -- and "commoners" (shomin 庶民) or "ordinary people" (heimin 平民), meaning everyone else. The term "min" means "people" in the sense of ordinary folk affiliated with an entity such as a village or country, or a vocation such as agriculture or hunting. It is clear here that "minseki" was in use before the promulgation and enforcement of the 1871 Family Register Law. In fact, it goes back to at least the 11th century in China. See Belonging in Japan past and present in the "Nationality" section for details. The term "ippan minseki" (一般民籍) -- meaning "general affiliate (peoples) register" was used in Grand Council of State Proclamation 429 of Meiji 4-8-28 (12 October 1871), which stipulated that "eta, hinin and such" -- appellations abrogated by Proclamation No. 428 of the same date -- were to be enrolled in general population registers as "commoners" (heimin 平民). Proclamation No. 115 of Meiji 4-4-9 (15 April 1872) The expression "jinmin koseki" (人民戸籍) also appears in the 1871 Family Register Law. My hunch -- which I am unable to substantiate at this time -- is that "minseki" is a reduction of "jinmin koseki" -- at least in cases when the "people" (jinmin 人民) were enrolled in registers by household (戸籍), which generally referred to a dwelling with an address. "Jinmin koseki" also appears in the title of at least one contemporary guide for people engaged in the registration business -- the equivalent of today's judicial scrivener (shihō shoshi 司法書士), who are authorized to prepare and at times file legal documents related to civil matters such as household registration, inheritance, conservatorships, naturalization, and real estate transactions and title transfers and the like. See Meiji-era household registration handbooks below for examples. The term "minseki" (民籍) generally refers a civil register (seki 籍) of affiliates (min 民) of a country or territory. To the extent that such registers embrace the entire population of a country's affilites -- and to the extent that a country's affiliates are enrolled in household registers -- "minseki" and "koseki" are synynomous with other and tantamount to "kokuseki" (kokuseki 国籍) in the sense of "nationality", though of the three terms are used differently. Otherwise, "minseki" signifies only the civil population (household) registers of a legal territory. 1874 Kōeki jukujiten definitions of "kokumin" and "minseki"The images to the right show "minseki" defined in both the graph-look-up (1874) and kana-look-up (1875) editions of Yuasa Tadayoshi's Kōeki jukujiten (廣広熟字典), a dictionary of Sino-Japanese compounds published a couple of years after the family register law came into effect in 1872. The definitions, while not rigorous, suggest that the term refers to a register of common people as "affiliates" (min 民) of an administrative territory. For a complete discription of the dictionary, and numerous examples of several other terms, see Belonging in Japan past and present in the the same "Nationality" section. "Minseki" in Japan's early population reports"Minseki" was the key word in the title of some population reports like Nihon Teikoku minseki kokō hyō (日本帝国民籍戸口表) "Japan Empire minseki household and population tables", published in 1895 (Meiji 28) by the Family Register Section (Kosekika 戸籍課) of the Police Bureau (Keihokyoku 警保局) of the Ministry of Interior Affairs (Naimushō 内務省). The bureau was established on 28 August 1872 in the Ministry of Justice ( Shihōshō 司法省), migrated to the Ministry of Interior Affairs on 9 January 1874, and operated until the Interior Ministry was dissolved by the Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces on 31 December 1947. The bureau's responsibilities included overseeing the enforcement of the Family Register Law and administration of the family (household) registration system, which are now under the oversight and control of municipal government offices. "Minseki" in Korea and Chōsen"Minseki" was used by the Korean and Japanese authors of the Empire of Korea's 1909 People's Register Law (民籍法 K. Minjŏkpŏp, J. Minsekihō). This law enabled the implementation of Korea's first comprehensive nationwide household registration system. It remained in force after Korea was annexed by Japan as Chōsen in 1910. Chōsen's houshold register system was gradually, but never entirely, Interiorized. It accommodated many features of Interior family law while retaining some elements of Chōsen family law. For example, from 1940, Chōsen's family registration system required Interior like sharing of a single family name by all members of the same family, but registers continued to record individual family clan names and their origins, which Chosenese continued to value when it came to marriage and adoption. "Minseki" in national censuses"Minseki" was used within the Empire of Japan to refer to the population register systems of the 4 legal territories that comprised its sovereign dominion -- Interior, Taiwan, Karafuto, and Chōsen. National censuses from 1920 to 1945 reported breakdowns of Japan's population by minseki and nationality (kokuseki 国籍). Japanese were broken down by minseki, and foreigners -- meaning people who do not possess Japan's nationality -- were broken down by nationality. Both breakdowns were based on a person's "honseki" (principle domicile register) status -- registration within one of Japan's territories, or within the territory of another country. Aliens were deemed (as a legal fiction) to have a honseki in another country, which made them a national of the country. People with no nationality were stateless aliens. See examples of census classifications immediate below. "Minseki" in Manchoukuo"Minseki" was used by the Manchoukuoan and Japanese authors of the Empire of Manchoukuo's 1940 Provisional People's Register Law (暫行民籍法 WG Chanhsing minchifa, PY Zanxing minjifa, SJ Zankō minsekihō). The enabled the first nationwide household population registration system in the country. |

||||||||||

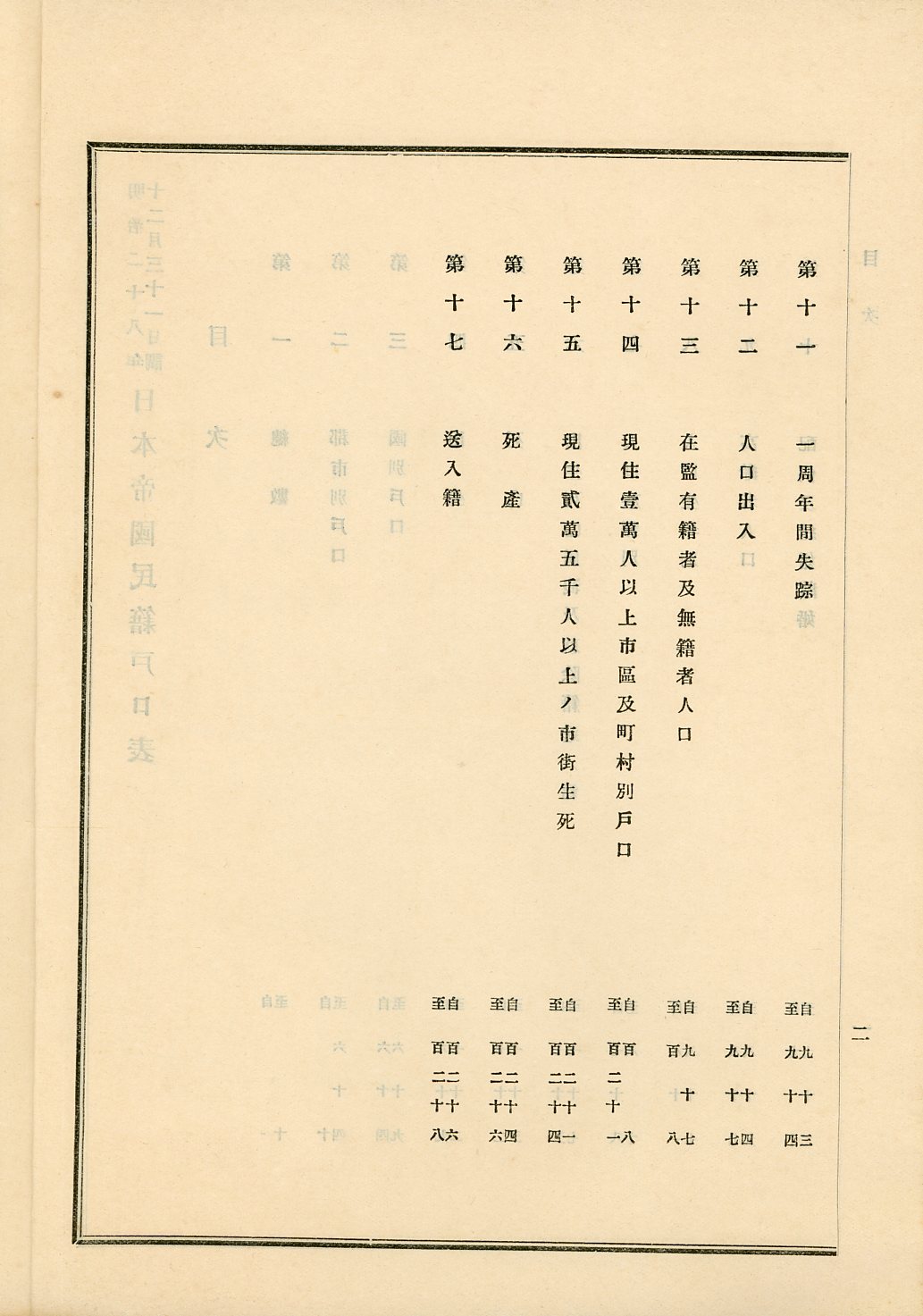

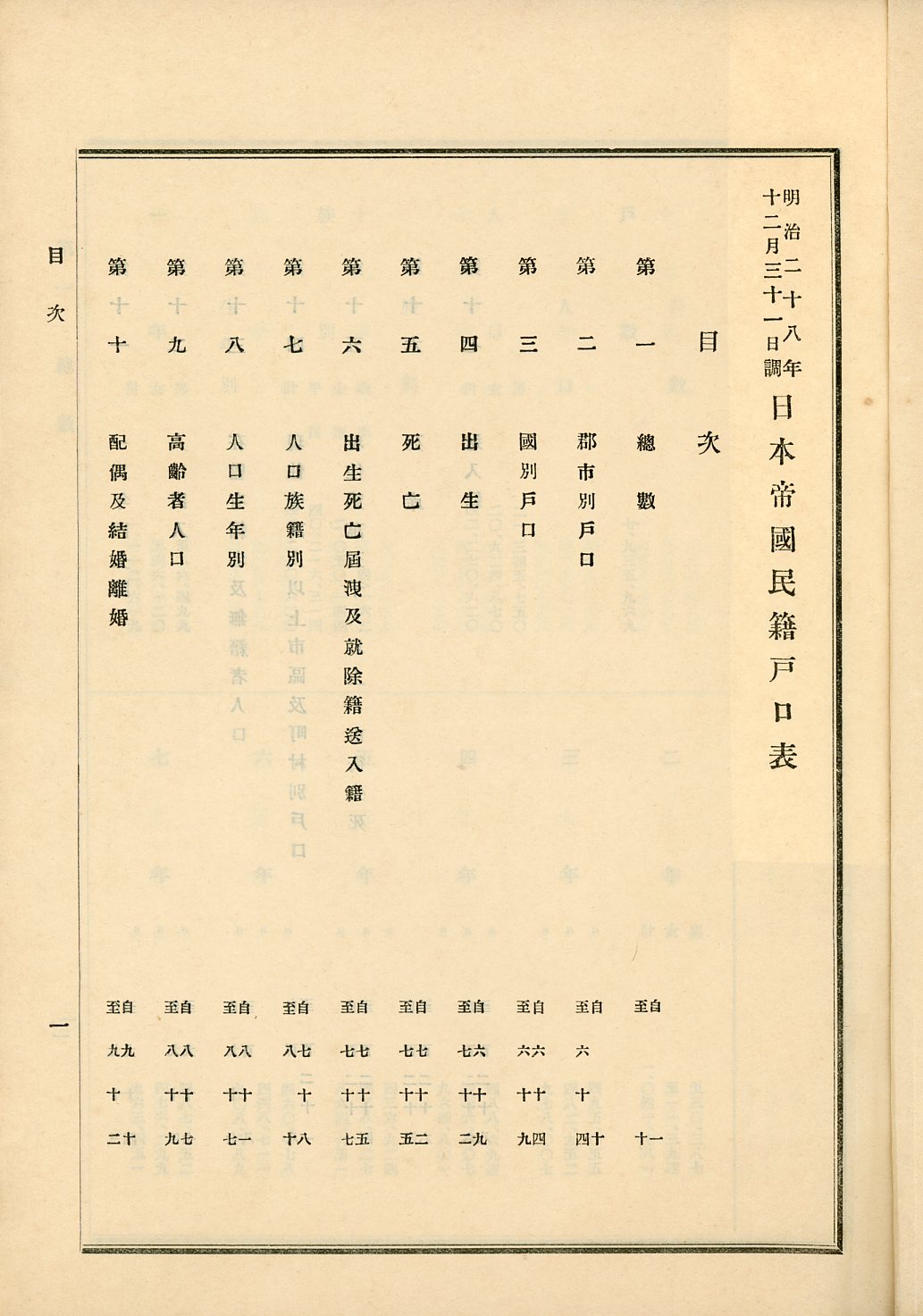

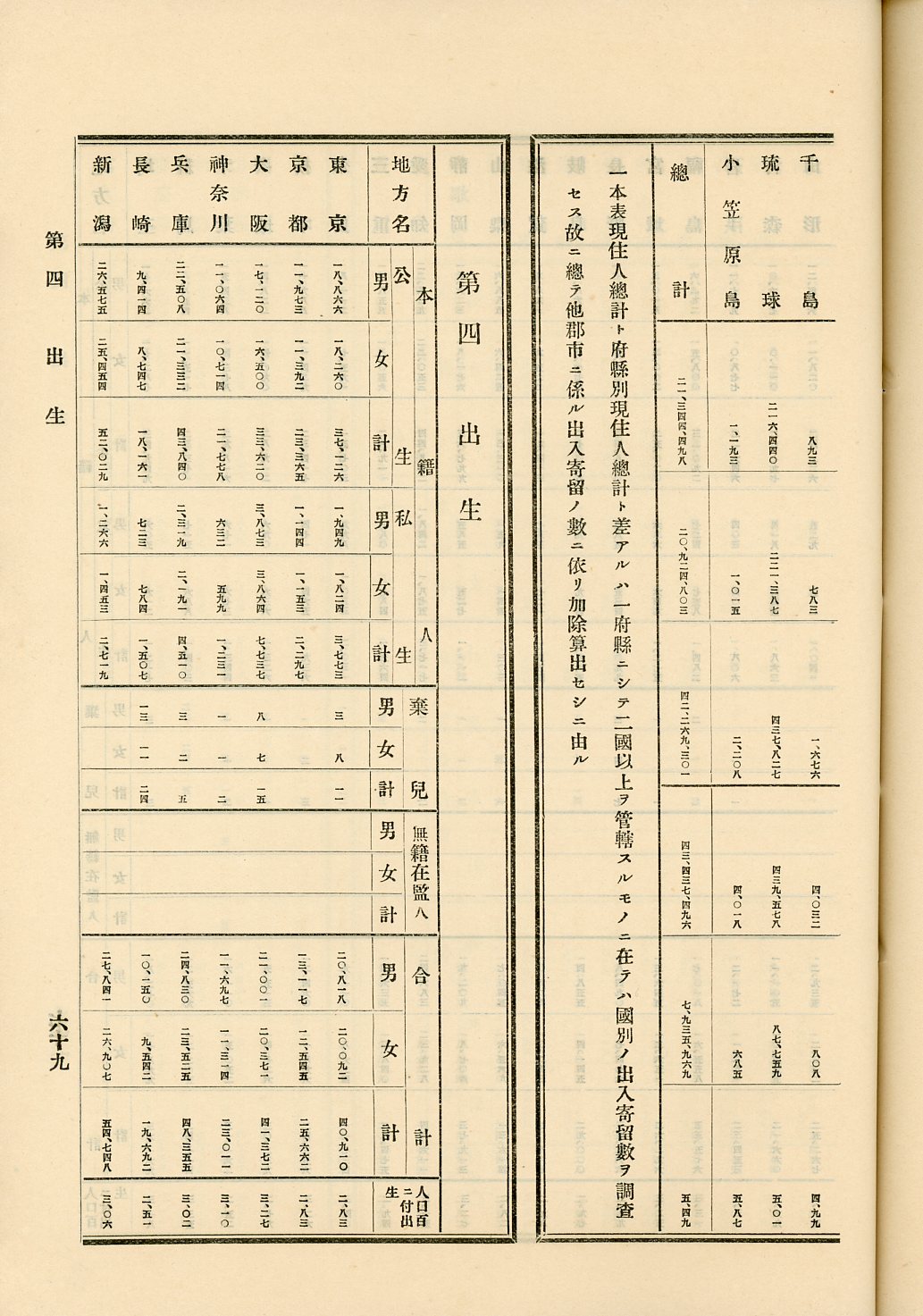

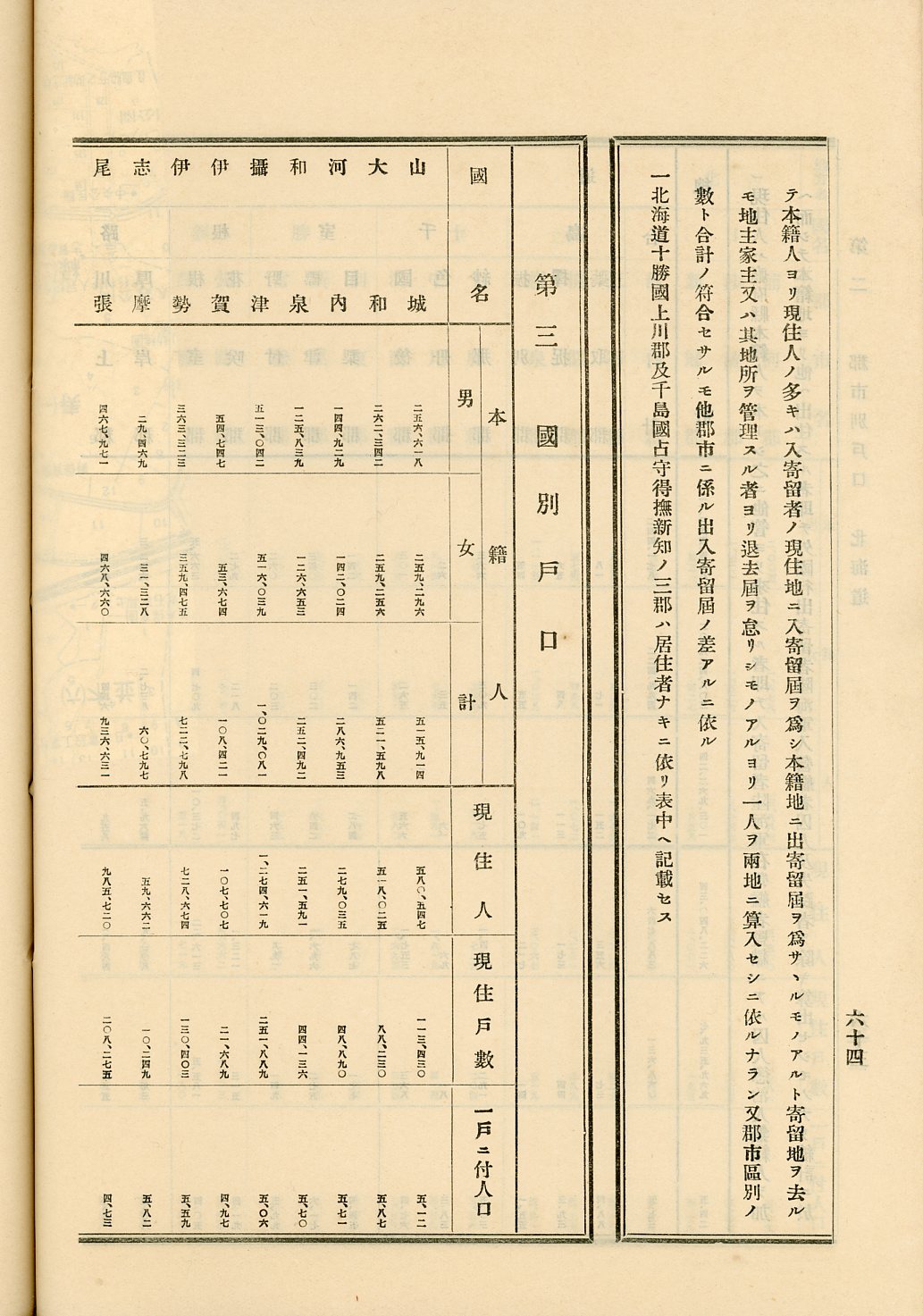

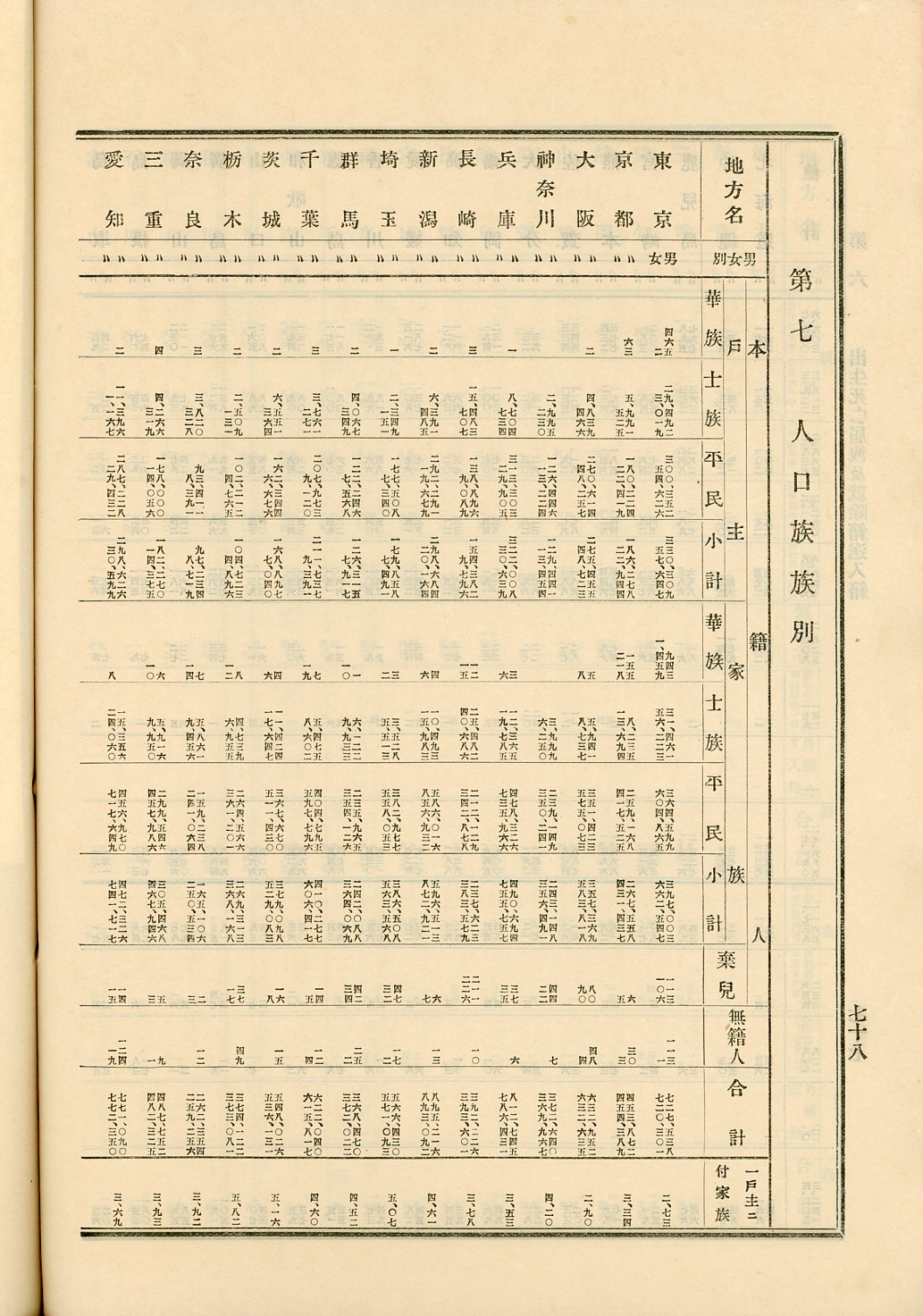

1895 Minseki households and populationsWho was born, who died, and who resided where,

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

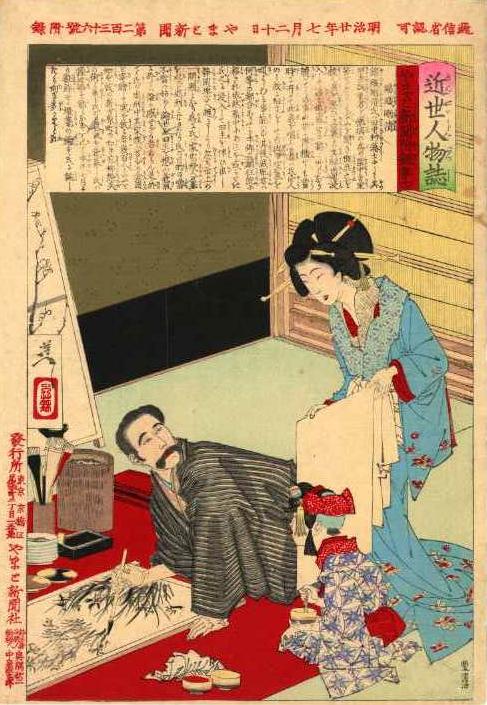

Goto Shinpei's involvement in Soma incidentFor an account of the Soma incident and Gotō's involvement in its investigation, see my article, Nishigori Takekiyo: Kinsei Jinbutsu Shi, Yamato Shinbun Furoku, No. 10, about Yoshitoshi's portrayal of Soma's former retainer Nishigori Takekiyo. The article includes an enlargeable scan of a copy of this woodblock print in Yosha Bunko. |

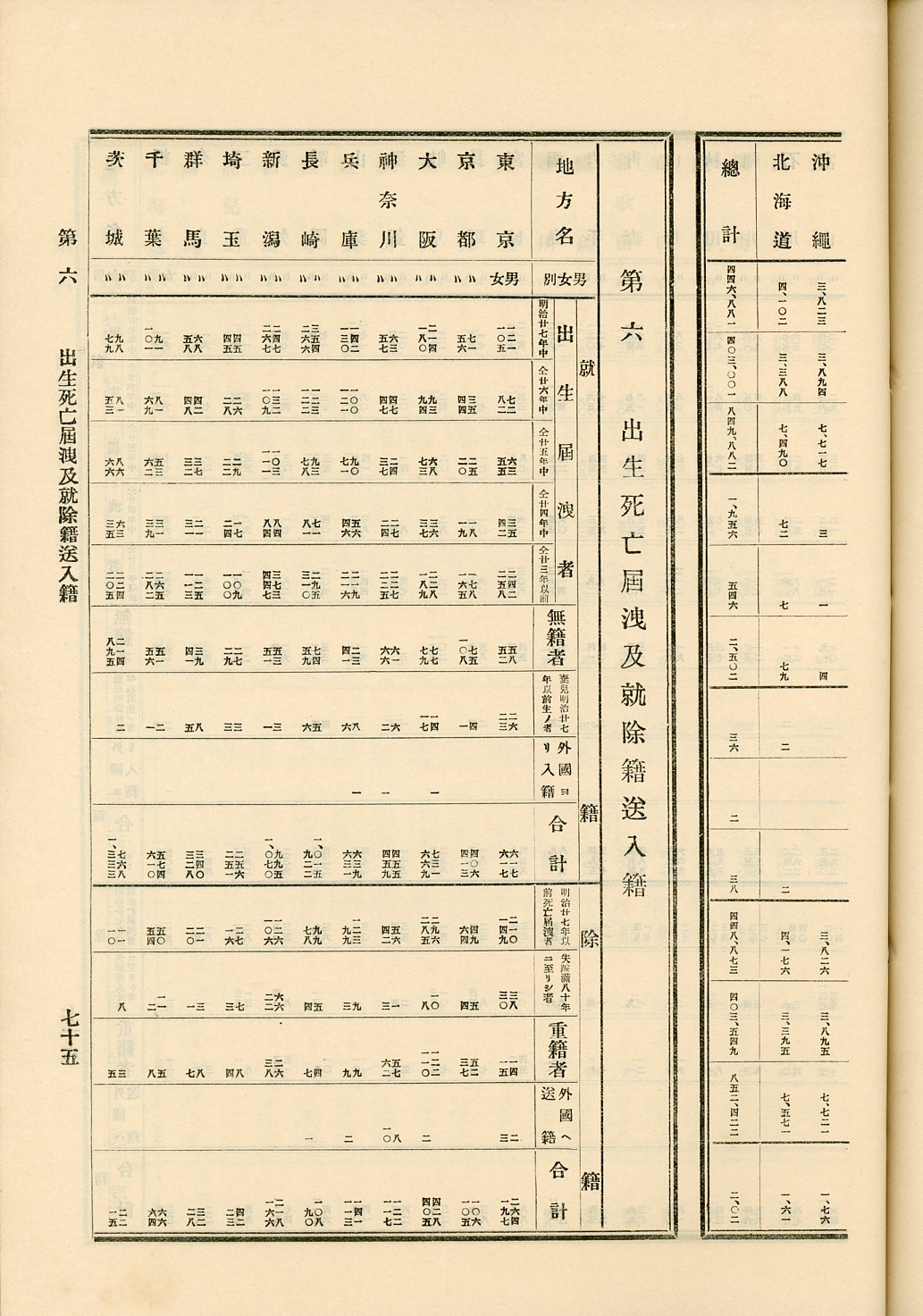

Table 6 (Page 76)

Delayed and other special status actions

Additions -- late reports of death et cetera Deletions -- late reports of death et cetera Migrations from and to foreign registersForthcoming.

Table 7 (Page 78)

Houshold populations, domicile by locality and sex, plus

occupants and households, and occupants per household, by locality

Domicile of head and family by status and sex,

abandoned children and unregistered people,

plus average persons per household

Forthcoming.

|

Table 6 in 1895 Nihon Teikoku minseki kokō hyō |

|

Terms in Table 6 title |

|

出生死亡届洩 |

birth and death notification omissions Counts of late or delayed filings of birth and death notifications. Such notifications were supposed to be made within 14 days of a birth or death. People missed filing deadlines for all manner of reasons. Late filings were generally accepted but queries might be made if there was suspicion of illegal activities. Some people have said that Japanese nationality is automatically acquired by children of Japanese parents, but this is not true in the sense that most people understand "automatically". Qualified children acquire Japanese nationality at time of birth only if a proper birth notification is filed with a municipal registrar if in Japan, or a Japanese consulate if outside Japan, in a timely manner. Late filing can result in failure to acquire nationality, as some parents have discovered. A law has effect only if applicable. Japanese nationality can be acquired by "automatic application of the law" only if the Japanese Nationality Law can be applied. And it can be applied only to births that are notified. Notification forms require information on the parents and other conditions of birth. Officials vet the information, and if they find it accurate, they apply the Nationality Law to determine whether or not, on the basis of the information, the child has Japanese nationality. Officials who vet notifications have no discretionary authority when it comes to interpreting the law. The effects of the law are automatic for children whose conditions of birth satisfy the law's criteria for acquiring Japanese nationality. |

就籍 shūseki |

establish register A new register is made -- or established or created -- for a child deemed to be Japanese through birth, or for a child or adult who later acquires Japanese nationality through adoption or marriage (old law), recognition or legitimation (old and present laws different), or naturalization old and present laws). Pursuant to a family court decision, if not appealed, a municipal registrar can also establish a register for (1) a foundling deemed to have been born in Japan (jus soli), (2) an unregistered child or adult with a known identity and past (usually jus sanguinis), and (3) an adult found wandering around, who suffers from severe amnesia, whose identity and past cannot be determined, but who exhibits speech, knowledge, and other traits that can only be understood as evidence of having been raised and probably born in Japan (jus soli) -- et cetera. |

除籍 joseki |

removal from register A person's name and related information may be removed or struck from a register for several reasons. If a register includes only the person who is to be removed, then the register itself is closed. A person in a register is removed from the register (1) when migrating to another register on account of marriage or adoption, (2) after death, (3) after renouncing or otherwise losing Japanese nationality, or (4) when the person is found in more than one register. Under pre-postwar family law, the head of a household could have a member expunged from its register -- disowned, disinherited, disenfranchised -- for behavior the head regarded as against the family's interests. Disowning is commonly called "enkiri" (縁切り) or "bond cutting". Under older family law, a head of household was empowered to cut off a son or daughter or other member of the family who, for example, took up with a woman or man the head did not accept. As overhauled in 1947, effective from 1948, Japan's family laws no longer recognize a head of household as such. The first person listed on a family register is now called the "hittōsha" (筆頭者) -- "person written at head [of register]" -- an artifact of the history of the register. Today's nominal "head" has no authority other than as an individual legal person who might also have parental, filial, spousal, or other such rights and duties derived from a status relationship as a parent, child, or spouse -- not from the artifact of being the first listed. |

送籍 sōseki |

sending register A person's family register -- meaning the person's domicile register or "honseki" -- could be "sent" or "transfered" from one municipality (local village, town, city, ward entity) to another, for various reasons. In the past, someone who was not a head of household needed permission from the head to leave the register and establish a personal or branch register, possibly at another address, possibly in another locality. Under the 1947 Constitution and subsequent revisions in the Civil Code and Family Register Law, an individual is free to change his or her honseki address, subject only to constraints imposed by the requirement that married couples and minor offspring share the same register. Whether people who share the same family register live together or separately is another matter. Japan's registration system is two-tiered. All Japanese have a "honseki" in a municipality within Japan's sovereign dominion, which establishes their affiliation with Japan, hence their possession of Japan's nationality, which is territorial. Japanese also have a legal residential address, which may be anywhere in Japan or abroad. If in Japan, they are enrolled in a "resident register" in the municipality where they actually reside. Rights and duties of municipal, prefectural, and national citizenship derive from municipal registration. The rights and duties of Japanese who legally reside outside Japan -- meaning they have filed notifications of foreign residency and therefore have no resident registration in Japan -- are derived from their honseki status in Japan, where establishes their nationality, not their residency. Most countries have multiple "local" and "state" affiliation systems, but only a few have residence registration systems as pervasive and inclusive as Japan's, which govern every aspect of civil life, from public schooling and healthcare, to suffrage and inheritance. |

入籍 nyūseki |

entering register A person in one register enters another register through marriage or adoption. Today, "nyūseki shita" is a commonly used as a synonym for marriage, especially by women, who are more likely to move to their husband's register, but even men who did not move to their wife's register may be heard to use "nyūseki" when saying they got married. Under the old Civil Code and Family Register Law, a head of household could refuse to accept the entry of someone as the spouse of a member of the family, or as an adoptee. Today, most people who marry, who had been in their parents' register, establish a new register as husband and wife -- regardless of which spouse adopts the other's family name. |

Terms related to "establish register" (shūseki 就籍) tallies |

|

出生届洩 |

birth notification omissions The figures in Table 6 show notifications filed during 1895 for births that took place during 1894, 1893, 1892, 1891, or 1890 or earlier, by sex, by prefecture. |

無籍者 musekisha |

person without register This term refers to a minor or adult who, for many possible reasons, has been growing up, or has grown up, without having been registered, and therefore has not existed in the eyes of the law. The term "mukosekisha" (無戸籍者) refers more specifically to a person who ought to have been registered in a koseki but was not -- where "musekisha" (無籍者) refers more generally to anyone who has not be registered, whether in a koseki as Japanese, or as an alien whether with or without a nationality. Reasons some people go unregistered There are many reasons that a child might not be registered. One of the most common reasons is the birth of a child to a woman has left or divorced her husband and has a child with another man. If only separated from her husband --or if, under the contested provision in the law, the child was born within 300 days of the divorce -- the child will be deemed to be that of her husband (ex-husband). In either case, the child cannot be registered as having another father, or as being its mother's out-of-wedlock child without a father on record, unless she persuades her husband (ex-husband) and he agrees to petition a family court to confirm that there is no father-child relationship. Some women end up unable to register their child because their social and/or emotional conditions are not conducive to confronting their husband (ex-husband). Other cases involve mothers who leave a hospital with their child without settling accounts with the hospital and obtaining a proper birth certificate, which is part of the birth notification form; mothers who give birth somewhere without a witness and, again, are unable to satisfy the birth certificate requirement; parents of children born through surrogacy, a reproductive alternative that is not at present (2021) recognized in Japan; parents one or both of whom may be registered, or have other reasons not to expose themselves to bureaucratic scrutiny; parents who are ignorant of the law or have religious or other ideological reasons not to become public cyphers -- ad infinitum. Abandoned children "Persons without a (family) register" do not include abandoned children (kiji 棄兒、sutego 捨児, 捨子) who have been found -- and have been duly registered as foundlings. Abandoned children -- foundlings -- exist in the eyes of law precisely because they have been found and deemed to have been abandoned. If a child's mother and/or father can be traced, then it's nationality is based on those of its mother and/or father if they are not stateless. If the child's parents remain unknown or turn out to be stateless -- and if the child is deemed to have been born in Japan -- then under place-of-birth (jus soli) provisions in Japan's Nationality Law (old and new laws), the child is regarded as Japanese, retroactive to its estimated date of birth, and is given a name and enrolled in a new family register. Such children, usually infants, will be protected in orphanages or other shelters, and will later be placed in foster homes or adopted. |

棄兒 |

kiji / Meiji 27-nen izen umare no mono |

外籍ヨリ入籍 |

gaikoku yori Nationality through marriage or adoption not naturalization Such status migrations -- acquisition or loss of Japanese nationality through marriage or adoption -- were no longer possible under the 1950 Nationality Law. Permission for a Japanese to marry or adopt a foreigner who stood to become Japanese through an alliance of marriage or adoption was obtained through an application filed by the head of the household that would gain a spouse or adoptee. The household head's permission was discretionary, as was the permission of the government officials who reviewed and approved the application. Japanese law differentiated between nationality derived through marriage or adoption, and nationality acquired through naturalization, in both nomenclature and statistics. Nationality through marriage or adoption was a family matter that began with family approval. Naturalization was a state matter that involved only the alien, who was at the mercy of the discretionary powers of only the government. Having Japanese family ties might improve an alien's chances of being allowed to naturalize, but the family had no agency in the governments decision. |

Terms related to "removal from register" (joseki 除籍) tallies |

|

明治廿七年以前 |

Meiji 27-nen izen shibō-todoke-more [no] mono |

失踪萬八十年 |

shissō man-80-nen ni itashi mono |

重籍者 jūsekisha |

multiple [double] registered person A person who qualifies for registration is allowed to be enrolled in only one register. A person might end up in two or more registers on account of a clerical error -- or because the person perceived an advantage in having two or more identities, possibly related to polygamy or another outlawed activity. A person found in two or more registers would be struck from all but the seemingly true register. |

外国へ送籍 |

gaikoku e sōseki Many Japanese forms have a "honseki" box in which Japanese write their honseki register address and foreigners write their nationality. Japanese law regards all foreigners as a having a honseki in their country of nationality that is tantamount to a honseki in Japan. This legal fiction is not stated in Japanese law but is implied by the metaphorical use of "seki" (籍) to mean a formal status of affiliation with a local, regional, or national entity, or even an affiliation with a college, established by some form of registration or enrollment. |

1930 national census reportInterior population by subnationality and nationalityInteriorites and Exteriorites

|

|||||

Minseki and kokuseki distinctions in 1930 census民籍国籍別人口 / 全国 Minseki kokuseki betsu jinko / Zenkoku [ Population by (imperial territorial) population registers or (alien) national registers / Entire country ] = prefectural Interior (Naichi) of Empire of Japan Start of Japanese "minseki" (territorial) classifications

内地人 Naichijin [Interiorites]

= Subjects of Japan in prefectural Interior registers

総数 Sosu [Total]

外地人 Gaichijin [Exteriorites]

= Subjects of Japan in Exterior (non-Interior) registers

総数 Sosu [Total]

朝鮮 Chosen (non-Interior territory)

台湾 Taiwan (non-Interior territory)

樺太 Karafuto (non-Interior territory)

Legally subject to Interior laws under 1918 Common Law

Integrated into Interior as Japan's 48th prefecture in 1943

南洋 Nan'yo [South Seas] (South Seas Islands 南洋諸島 Nanyo Shoto)

= German Pacific islands occupied by Japan in 1914

Recognized as being occupied by Japan in the 1919 Treaty of Versailles,

and administered by Japan under a League of Nations mandate until 1945

Occupied and administered by U.S. military forces until 1947

Administered by U.S. as U.N. trust territory from 1947-1994

Start of foreign "kokuseki" (nationality) classifications

外国人 Gaikokujin [Aliens]

総数 Sosu [Total]

中華民国 Chuka Minkoku [Republic of China (ROC)]

[ 省略 ] [ 36 other foreign states,

plus other foreign states,

omitted here ]

|

English reports

See 1936 Japan Year Book for examples of how Japan's territorial census figures were differently reported in Japanese and English.

Subnationality

I regard "minseki" in the context of Japan during its imperial years, when the term was used to differentite territorial registers within Japan's sovereign dominion, as "subnationality" -- i.e., a territorial legal status within an overarching "nationality" (kokuseki 国籍) status. The 1920, 1930, and 1940 censuses, for example classified Japanese according to the "minseki" of their "honseki" (本籍) -- the territoriality of their principle domicile register -- whether it was affiliated with the prefectural Interior (Naichi 内地), Chōsen (朝鮮), Taiwan (台湾), or Karafuto (樺太).

The need to differentiate Japanese by territoriality -- i.e., subnationality -- was anticipated by the 1918 Common Law. As a domestic law of laws, the Common Law determined which territory's laws applied in interterritorial civil matters, such as alliances marriage or adoption, and dissolutions of such alliances, between Japanese affiliated with different territories

Say, for example, that a Chosenese man and an Interiorite woman marry. This is a private matter, governed by the laws of Chōsen and the Interior. She might migrate to his Chōsen register and become Chosenese. Or he might migrate to her Naichi register as an "incoming [adopted] husband" and become an Interiorite.

Both would continue to be Japanese, since both territories were part of Japan's sovereign dominion, and Japan's nationality is an artifact of territorial affiliation. Both statuses -- nationality and subnationality (territoriality) -- were strictly civil status. Race or ethnicity have not been matters of law in Japan, much less of registration or change of registration.

"Minseki" as "subnationality"Territorial affiliation not ethnicity"Minseki" (民籍) is an older term for registers (seki 籍) of people (min 民) residing in, and belonging to, a locality under the control and jurisdiction of a lord or other authority with reason to want to know who lives where -- typically for purposes of levying taxes or conscripting people for military service or labor. "Min" as word for "people" typically implies politica affiliation with a demographic entity, whether a village or a state, in the sense of being subject to the entity's laws or other forms of authority, and owing the entity and or its overlords one's allegience. The term "minseki" was used in Japan in the middle of the 19th century, during the late Tokugawa and early Meiji periods, to mean the registers of commoners. The title of a 1895 population report, of enumerations of people in Japan by age, sex, and other categories in household registers, uses "minseki" or "peoples (civil) registers" as a synonym for "koseki" (戸籍) or "household (family) registers". Membership in a koseki in Japan -- possession of a "honseki" (本籍) in Japan -- was tantamount to having the "standing of being Japanese" (日本人タルノ分限) until the adoption of the term "kokuseki" (国籍) to mean "nationality" shortly before the promulgation and enforcement of Japan's 1st operational Nationality Law (Kokusekihō 国籍法) in 1899. The 1899 Nationality Law, which originated as an Interior (Naichi 内地) law, was extended to Taiwan the same year. Taiwan, when ceded to Japan by China in 1895, became part of Japan's sovereign dominion. It came, however, with its own legal system, including population registers and regulations for their administration. Japan's nationality is territorial, in the sense that it is an artifact of membership in a household register under the control and jurisdiction of a municipality (village, town, city, or ward) within Japan's sovereign dominion. Hence people in Taiwan who remained affiliated with Taiwan register, through membership in a Taiwan register, rather than declare an affiliation with a foreign state, had already become Japanese when the Nationality Law was extended to Taiwan. Japan's Nationality Law does not declare who is Japanese, but determines who becomes Japanese or ceases to be Japanese when applied to individuals and their personal circumstances. Because the law also began to operate in Taiwan, it's provisions for naturalization through permission, as well as for acquisition of Japanese nationality through marriage or adoption into a Japanese household, and loss of Japanese nationality through marriage or naturalization, meant that (1) aliens could naturalize in Taiwan, or become Japanese through marriage or adoption into a Taiwan register, while Taiwanese could lose Japan's nationality through marriage to an alien or naturalization in another country. The Empire of Korea's 1909 Minsekihō or "People's register law", established with the insistence and assistance of Japanese advisors in Korea, then a dependency of Japan, doubled as a national register (nationality) law, much like Interior and Taiwan household registers were also registers of Japanese nationality. In other words, enrollment in a household register under Korea's minseki system implied possession of Korea's nationality. When Japan annexed Korea as Chōsen in 1910, Chōsen -- like Taiwan -- came with its own legal system, including minseki population registers. Korea's Minsekihō continued to operate in Chōsen as a territorial rather than national register law. And because Chōsen was part of Japan's sovereign dominion, membership in a Chōsen minseki was deemed to mean possession of Japanese nationality. In other words, people in Taiwan and Chosen household registers, as registers under Japan's sovereign control and jurisdiction, were Taiwanese and Chosenese by regional territorial status within Japan, but were subjects and nationals of Japan, hence Japanese both nationally and internationally. Japan's earliest national censuses, which enumerated people living throughout the Empire of Japan, including territories within its sovereign dominion (Interior, Taiwan, Karafuto, and Chōsen), but also territories outside its dominion but under its legal control and jurisdiction (such as Kwangtung Province and the South Sea Islands), broke down people by "kokuseki minseki" in 1920 and "minseki kokuseki" in 1930. Both breakdowns amounted to classifying people affiliated with Japan by their regional "minseki" status, and aliens by their country of nationality. Since 1918, Japan had a domestic Common law, a domestic law of laws that determined which regional law within the Empire of Japan would apply in private matters between legal persons of different regionality within the empire -- Naichi, Taiwan, Karafuto, Chōn, and so forth. Because "regionality" or "territoriality" is a sub-category of "nationality", I have called minseki statuses in Japan "sub-nationality". Legally, it compares with considering someone who legally resides in, say, California a "Californian" as a matter of state affiliation, within the broader category of "American" as a matter of nationality. Before becoming Japanese, I resided in Japan as an alien. The question arose as to how my assests in Japan would be treated should I die in Japan. Inheritance laws in Japan's Code Code did not automatically apply to me. Under Japan's Laws of laws, which govern determinations of applicable laws in private international matters, my assets would be subject to "home country laws" (hongokuhō 本国法) -- i.e., the laws of my country of nationality. Since I was an American, most people would think that my "home country" was the United States. It would have been in a criminal matter involving extradiction or deportation. But in private matters such as disposition of personal assets in case of death, my "home country law" was California law. The United States is a federation of states which have their own constitutions and civil and penal codes, among other laws that make them all but sovereign states like Japan. As it turns out, because I was legally domiciled in Japan California law deferred to Japanese law. So my children would be able to inhert whatever I leave through the application of Japan's Civil Code. I became Japanese, so my former status as an American affiliated with California -- a American of California regionality or territoriality, or California sub-nationality if you will -- is moot. "Honseki" as a legal fiction"Honseki" (本籍) -- a keyword in both population register and census reports -- means "principal (primary, permanent, home) register". It refers to the locality where one "belongs" as a matter of civil record -- an address within a municipality or province or other administrative region within a country. Japanese nationality is territorial in that anyone who possesses a "honseki" within Japan's sovereign domininion is regarded as possessing Japan's nationality. Aliens -- people who don't possess Japan's nationality -- are deemed to have a "honseki" in their country of nationality. And on Japanese administrative forms, in the "honseki" (本籍) or "honsekichi" (本籍地) box where Japanese write their "honseki" address, aliens write their country of nationality -- or "stateless" (mukokuseki 無国籍) if they have no nationality. When I was an American, I wrote 米国 (Beikoku) -- meaning "USA" -- in honseki boxes on Japanese forms. My honseki address is the first part of my postal address down to but not including my house number. It begins with a prefecture, followed by either a county and then a village or town, or a city, then a the name of a neighborhood or other district of the municipality, and by at least 1, but usually 2, and less commonly 3 numbers representing parcels within parcels within parcels of land. A a full postal address will include the number of the lot or building thereon and possibly a unit or room number therein. Practically all people in Japan have distinct mailing addresses. I share my honseki address with several neighbors within the same larger block. Our postal addresses include a number which is specific for each lot. My daughter, on the other side of town, lives in a home that was built at the same time as several others when a parcel was subdivided. All homes share the same street and house address down to the final number. Only the names of the addresses are different. Without a name, or just "Resident", delivery people don't know where to go. This is not common but neither is it that rare. My residential address happens to be my honseki address address, because I was living at my present home when I naturalized. I could have chosen any other address, in principle, including the address of the Imperial Palace or the Prime Minister's residence, though of course local registrars would have discouraged me from doing so. My daughter and her husband and children are legal residents of the city having jurisdiction over their home, but their honseki address is in a differen municipality in a different prefecture. Their Japanese nationality, like mine, is linked to their honseki address, not their legal residence. They can move anywhere in the world, and their legal residence will change, but their honseki address will remain the same -- unless they change it. So long as they change their honseki address to another address within Japan's sovereign dominion, they will remain Japanese. Naturalizing in another country is deemed as a change in their honseki address to an address outside Japan's sovereign dominion, hence they stand to lose Japan's nationality. Having a "honseki" is a legal reality for Japanese, for whom it represents an actual physical record -- in the form of a "koseki" or "family register" linked by its nominal address with a locality -- a named and numbered parcel of Japan's sovereign dominion. For most Japanese, their "honseki address" (honsekichi 本籍地) is a "place" or "locality" (chi 地) where a living parent or grandparent may still reside. They themselves may have been raised there, and they may visit during holidays when families commonly get together. Even if their parents or grandparents die, their honseki address may remain the same -- even if new owners acquire the home on the lot, or the home is torn down and rebuilt, or the lot is renamed or renumbered. Even if they change their honseki address to another locality, they may visit family graves in the "home town" or "home country" locality. Some Japanese refer to their present or childhood "honseki" as their "kuni" (国), their "home province" or "home town" -- or as their "shusshinchi" (出身地), their "place of origin" or "native place" or "birthplace". Historically, migrants and refugees from other places, who arrived in a territory reached by the authority of the Yamato court, were settled in a locality within the dominion, and enrolled in its registers, in return for submitting to the emperor's authority in what amounted to a change of allegiance. The term for this process was "kika" -- which more than a millennium later was used to in Japan's 1899 Nationality Law to mean "naturalization". In other words, membership in the population that owed allegiance to the court -- to the reigning tennō (emperor, empress) -- became a matter of settlement and registration in a locality within the court's realm. The "identity" established by local registration was primarily local, as the locality -- while part of the imperial realm -- was also part of the province within the domain of a local authority who was allegiant to the Yamato court. The province was a "kuni" (國), and provincial people were "kokumin" (國民), which signified that they were "affiliates" (min 民) of province. As late as the 1895 population report, some statistics are reported by "kuni" (國) -- corresponding roughly to "provinces" or "countries" within the "domains" (han 藩) that had been nationalized as prefectures. "Japanese territory" as perceived by JapanNote that the territorial equivalency of honseki with nationality is based on honseki affiliation with Japan's national territory as defined by Japan -- including territories that Japan claims but either does not or cannot actually occupy for the purpose of control and jurisdiction. Japan claims that Takeshima (竹島) is part of Shimane prefecture and that the Southern Chishima (南千島) islands ("Northern Territory" Hoppō Ryōdo 北方領土) are part of Hokkaidō prefecture. But the Republic of Korea (ROK) claims, occupies, and controls Takeshima as Dokdo, and Russia claims, occupies, and controls the Southern Chishima Islands as part of the Kurils. Japan has formally claimed the Sentaku Islands (Sentaku Shotō 尖閣諸島) since 1895 and had regarded them as part of Yaeyama county (Yaeyama-gun 八重山郡) in Okinawa prefecture since 1 April 1896. In 1971, after the United States confirmed that it would return Okinawa "including the Sentaku Islands" to Japan in 1972, first the Republic of China (ROC), and then the People's Republic of China (PRC), insisted that the Tiaoyutai (ROC) aka Diaoyu (PRC) islands belong to them. PRC, which claims that ROC belongs to it, as of now (2021) patrols and sometimes crosses the perimeter of Japan's economic zone around the islands and insists that it will not allow Japan to actually possess the islands. The Senkaku Islands are now part of Ishigaki city on Yaeyama. No one lives there today. There was a fish processing plant on the main island during the early 20th century, but the islands became uninhabited shortly before the start of the Pacific War. A lighthouse was built on the main island and couple of goats were grazed there by an activist group, but the activists left and the goats stayed. Some research groups have conducted geological, zoological, and botanical surveys on the islands. Today, however, no one sets foot on the islands. There are, of course, no Japanese municipal government offices on any of these disputed territories. Records were probably kept of the fish plant employees and others who lived on the Senkaku Islands, but my guess is that their registers were not affiliated with the islands. Takeshima, a much smaller group, was sometimes visited but does not seem to have occupied -- until recently by some Koreans. When the Soviet Union invaded Karafuto and the Chishima islands in the closing days of the Pacific War, Japan evacuated Karafuto and Chishima residents, and their household registers and other records, to Hokkaido, where most residents resettled with new register addresses. Today however -- because Japanese are free to affiliate their "honseki" with any part of Japan's sovereign domain as defined my Japan -- about 300 Japanese have established honseki addresses in these contested territories. The 26 January 2011 issue of Sapio magazine reported that, between 2008 and 2010, honseki increased from 118 to 132 in the Northern Territory, and from 39 to 50 in Takeshima. The same article estimated that about 20 Japanese had established honseki in Sentaku. It also said that some 210 people had honseki addresses for Okinotorishima Tō (沖ノ鳥島), a coral surrounding a few rock outcroppings reinforced with ferro-concrete tetrapods and concrete encasings, that are part of the Ogasawara Islands that define Ogasawara village. ROC, PRC, and ROK claim that the shoal does not qualify as a territory that warrants Japan's claim to a 200 nautical mile economic zone around the shoal -- the southermost part of Japan, in the Philippine Sea, below the Tropic of Cancer. "honseki" and "genkyo" or "jcrucial to both the the population report and the census reports. Closely associated with "honseki" is "koseki" -- Underpinning the Lurking behind thereportsand the 1930 title speaks of d "honseki", the 1920 and 1930 census reports speak of "Few writers about Japan in English pay close attention to the meanings of Japanese terms like "kokuseki" and "minseki", or "honseki" and "koseki", on their own terms. The order of familiarity among Japanese speakers is "koseki" and "honseki", which are closely related but not quite synonymous -- followed by "kokuseki", which is an artifact of "honseki". "honseki" is the most important term, as -- and most Japanese speakers will not be familiar with "minseki""Kokuseki" and "koseki" are the most readily translated by widely shared translation tags like "nationality" and "family register". "Minseki" and "honseki" will cause translators more trouble because they lack widely shared tags. likely to be translated readily translated, while "minseki" and "honseki" is the least encountered term even in Japanese, and "honseki" the most important Of these two terms, "kokuseki" is the most universally understandable because every state in the world has a word that corresponds to it -- and in English, including American English, that word is "nationality" (not "citizenship"). In all countries, "nationality" is a raceless, non-ethnic legal status as a member of a state'sthat word is "nationality" easily understood "Minseki" is the least encountered term and lacks a widely shared translation. "Honseki" is the most important term but also lacks a widely shared translation. arethough understanding their meanings is is translated "nationality" or -- less accurately -- "citizenship". So long as "" (not accurate)less accurate) or (more likely, and less accurately) s of distinctions made in Japanese terminology, in their own terms. Rather than examine how |

||||||

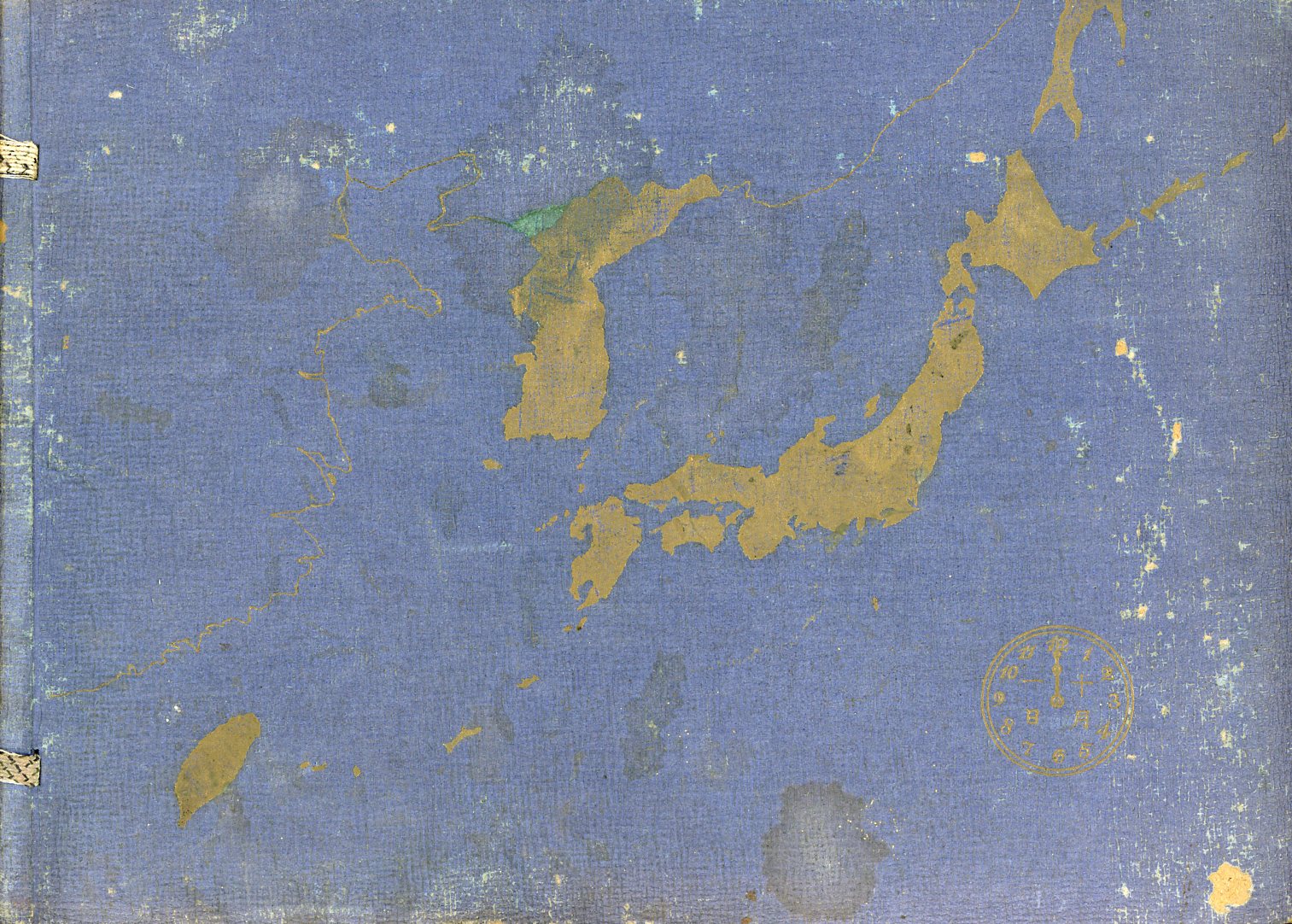

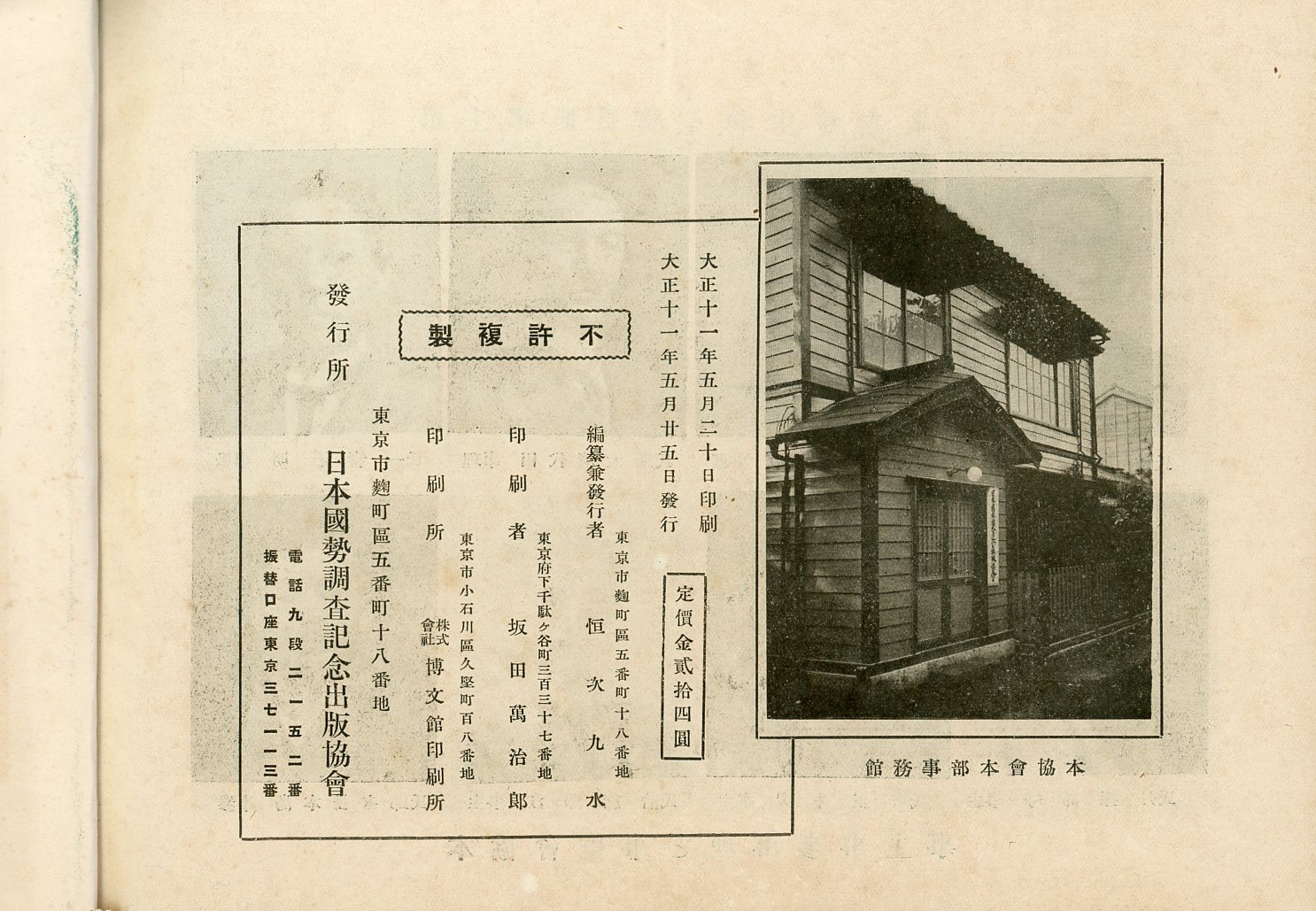

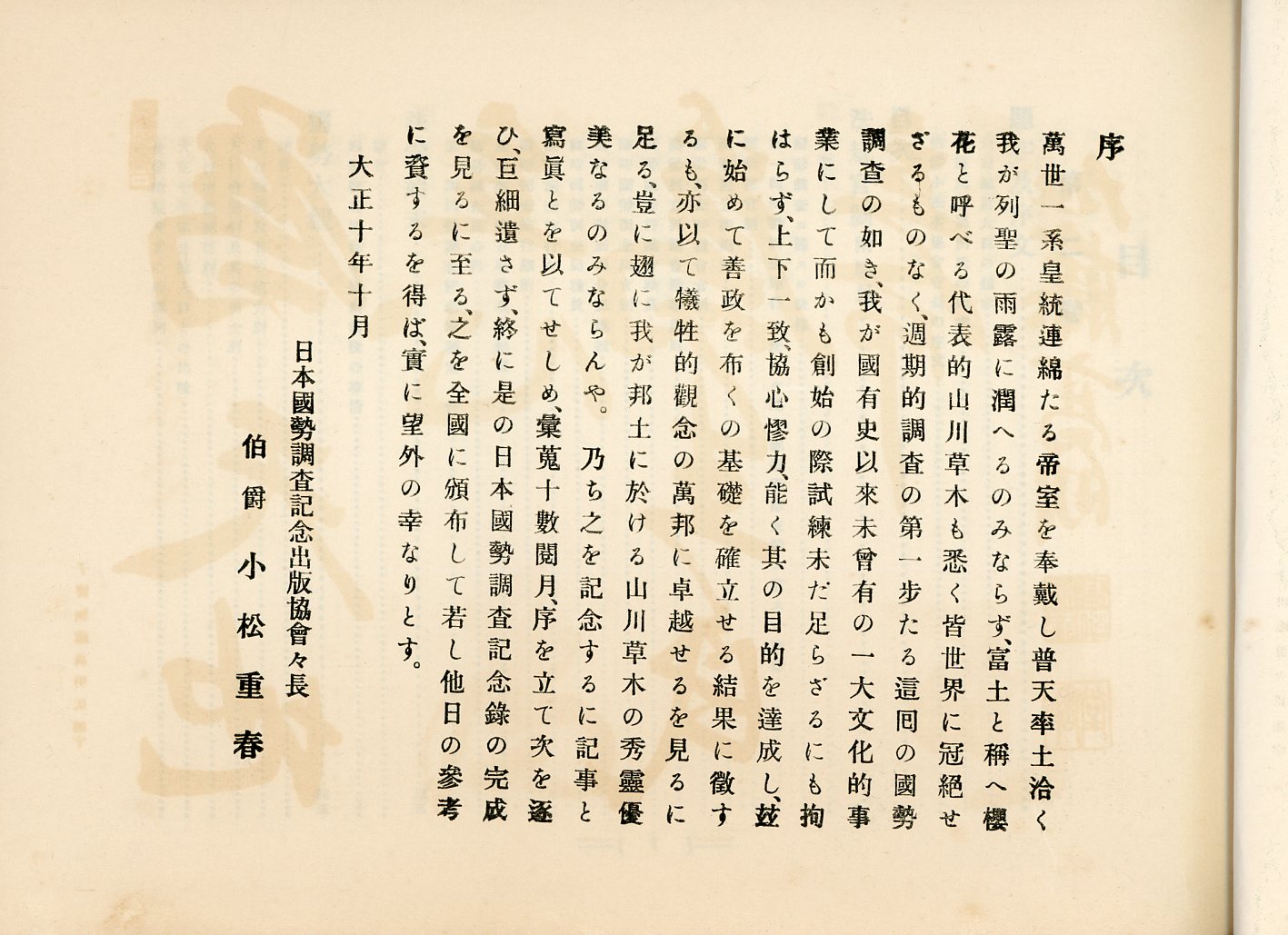

1920 Japan national census commemoration"Investigate without omitting anyone""Report [matters] as they are"恒次九水 (編輯兼發行) Tsuneji Kyūsui (compiler-cum-publisher) Attributed and dated materials in front matter of Volume 1 are as follows. 25 May 1922 Gosatasho 御沙汰書 "Imperial sanction" Tūchō "Notice" 15 January 1921 (Kunji "Directions") November 1920 (Jo "Preface") 1 October 1921 (Hanrei "Explanatory notes") 大正九年十二月二十八日 (御沙汰書) 大正十年一月十三日 (通牒) 大正十年一月十五日 (訓示) 大正九年十一月 (序) 大正十年十月一日 (凡例) The volumes shown to the right the Aichi prefecture edition of the 3-volume set of publications commemorating the complete and the success of Japan's 1st "Kokusei chōsei" or "National census" in what was foreseen as the start of a mission to evaluate the country's population every 5 years. Volumes 1 and 2 are the same for all prefectures. Volume 3 introduces the taking of the census in a specific prefecture, and consists mostly of photographs and information on each census official and census taker in the prefecture. members of the local teams of census takersThe first document in Volume one is a facsimile of a handwritten request dated 25 May 1922, from the Imperial House Minister Viscount Makino Nobuaki (牧野伸顕 1861-1949) to Baron Komatsu Shigeharu (小松重春 1886-1925), conveying that Tsuneji Kyūsui, compiler and publisher of Japan national census commemorative book, in 3 parts, be presented to the emperor and empress [Yoshihito (Taishō) Sadako (Teimei)] and the crown prince [Hirohito (Shōwa)]. The 3 volumes in the Yosha Bunko copy the set for Aichi prefecture have brown covers and the wrapper is blue. Another copy of only Volume 1 in Yosha Bunko, from an unknown set, has a black cover. Other volumes sold by antiquarian book deals have either brown or black covers. Each volume is bound with strings between two board covers measuring 26.2 cm wide and 19.0 cm tall. The 3-volume set was distributed in a box cover closed with what is called a "shitsu" (執SSSS. There appears to have been a set for each prefecture, and some of the volumes went through multiple printings. An antiquarian dealer offered a set from Shiga prefecture in which the 1st and 2nd volumes were 6th printings and the 3rd volume was a first printing. 一・二巻:6版 三巻:初版 The pages, all glossy, are A binding error resulted in three copies of the "Imperial sanction" (gosatasho 御沙汰所) transmitted by Grand Chamberlain Baron Oogimachi Sanemasa (正親町実正 1855-1923) to Cabinet Prime Minister Hara Takashi (原敬 1856-1921).Kei (年the "Gosatasho" The contents include numerous photographs beginning with portraits of the highest ranking members of the imperial family other than the emperor and his immediate family, followed by and explanations of the purpose of the census, how it was conducted, and how various figures were compiled from survey sheets, and examples of the sheets. There are also overviews of censuses in other countries. 大正9年10月1日国勢調査の理由や実行の記録を写真で纏めたものです。 Pages 64-65 国勢調査の目的 日本国勢調査記念録 [147] The census-taker slogans on the cover read "Investigate without omitting anyone" (Hitori mo morenaku chōsa suru koto (一人も漏なく調査すること) and "Report [matters] as they are" (Ari no mama shinkoku suru koto 有りのまま申告すること). The preface by Navy Vice Admiral Baron Nashiha Tokioki (1850-1928) reiterate that the census takers are to "carry out the investigation accurately, without omitting anyone". The "Introduction" s the slogans on Two terms caught my eye when purusing Volume 1 of The 1920 census commemoration book. Beginning in 1920, Japan began conducting empire-wide censuses based on door-to-door canvassing. The censuses sought to count everyone living in the territories that defined Japan's sovereign dominion, and in the territories under Japan's legal control and jurisdiction outside its dominion. Some tallies were based on place of birth, others on residence, yet others on locality of primary domicile or "honseki". As Japanese nationality was territorial, people in family registers affiliated with the territories that made up Japan's sovereign dominion -- the prefectural Interior (Naichi), Chōsen, Taiwan, and Karafuto -- were subjects and nationals of Japan, hence were Japanese by nationality and Interiorites (Naichijin). Chōsen and Taiwan came with their own legal systems, including household registers and the family laws that governed them. Karafuto had been under Japan's control and jurisdiction for quite a while before it was traded to Russia in 1875 for the northern Chishima islands, and when Russia ceded the territory to Japan after the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905), Japan quickly "Interiorized" Karafuto to the point that, under the 1918 Common Law, a domestic rules of laws, Karafutoans was treated under Interior laws in cases of private matters like marriage and adoption between Karafutoans and other Japanese -- Interiorites, Chosenese, and Taiwanese. Pursuant to a League of Nations mandate, the South Seas Islands (Nan'yō Shotō 南洋群島) were consigned to Japan's administration for the purpose of control and jurisdiction but not sovereignty. The islands, formerly been under German control and jurisdiction, had had occupied by Japan in 1914 at the start of the what became World War I, during which Japan was a member of the Allied Powers. The territory was formally called "I'nin-Tōchi-ryō Nan'yō Shotō (日本委任統治領南洋群島), which means "Japan mandate-governed territory South Sea Islands", and it was governed by the "Nan'yō-chō" (南洋廳). The term "chō (庁), commonly used today in the sense of "agency" or "headquarters", signified a imperial government organ that served as the "government" of the territory. People affiliated with the islands were called "Nan'yōjin" (南洋人) or "South Sea Islanders" -- a short form of "Nan'yō Shotō jin" (南洋諸島人). Japan lost most of the islands during the last year or so of the Pacific War and surrendered the others after the war. The mandate began on 7 November 1919 pursuant to the Treaty of Versailles, and ended with the establishment on 18 July 1947 of the "Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands" (Taiheiyō Shotō Shintaku Tōchi Ryō 太平洋諸島信託統治領). Chosenese (Chōsenjin), Taiwanese (Taiwanjin), and Karafutoans (Karafutojin) were Japanese by Japanese, but their domicile registers were affiliated with territories outside the Interior. Legally, South Sea Islanders had no nationality, but as they were affiliated with a territory under Japan's legal control and jurisdiction, they had territorial identities within the Empire of Japan. They were duly registered in local family registers, and the few South Sea Islanders that traveled or resided elsewhere in the empire carried transit permits that identified them as South Sea Islanders. Hence they enumerated as "South Sea Islanders" in national censuses. The 1920 census, taken less than year after the start of the mandate, counted a total of 3 South Sea Islanders in the prefectural Interior -- all in Tokyo prefecture. Nomenclature in 1920 censusThe 1920 census was taken barely 10 years after Japan annexed Korea as Chōsen. The empire was still reeling from the 1 March 1919 independence uprisings in Chōsen and elsewhere. Chosenese became Japanese through the artifact of Chōsen's incorporation into Japan's sovereign dominion, but the Nationality Law was never formally applied to the peninsula. Customary law provided for ordinary nationality acquisition through birth but not for naturalization (which began with the 1899 Nationality Law) or renunciation (which became possible through a 1916 revision in the 1899 law). Taiwan, by 1920, had settled into a fairly peaceful colony after 25 years under Japanese rule, which at first met considerable resistance from some Taiwanese. Taiwan was not a contested territory during the Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895), but Japan had been involved with Taiwan for many years and demanded that China cede it the islands as part of the settlement under the Simonoseki Treaty. The treaty provided Japanese nationality to people in Taiwan who did not formally declare and confirm their status as subjects of another country. And Japan extended its 1899 Nationality Law to Taiwan, which thus became on a par with the Interior as far as nationality was concerned. Karafuto -- the southern half of Sakhalin -- had essentially been under Japan's control and juristiction in 1875 when Japan traded its interests in Karafuto for Russia's northern Kurils, which Japan calls the northern Chishima islands. Karafuto became part of Japan's sovereign dominion in 1905 when Russia ceded the territory to Japan as partial settlement following the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905). The Portsmouth Treaty provided that people in Karafuto who did not chose to remain Russian would be nationals of Japan. Customary law determined nationality matters until 1924, when Japan extended the operation of the Nationality Law to Karafuto. Some Karafuto Ainu had relocated to Hokkaidō rather than remain in Karafuto and become Russians in1 1875. By 1905, Karafuto Ainu, significantly Russified, became Japanese, as did other indigenous people in the territory. Hokkaidō Ainu became essentially Japanese when the largest part of "Ezo" (蝦夷) or "Ezochi" (蝦夷地) was nationalized and incorporated into Japan's sovereign dominion in 1869 as the territory of Hokkaidō. In 1882, the territory became 3 prefectures, which were merged as Hokkaidō prefecture in 1886. In 1920, Hokkaidō Ainu were still enrolled in the distinct (segregated) registers which had been established in Ainu villages before the formation of the prefectures -- to somewhat simply a more complex historical reality. Though still in their own registers, Ainu were nonetheless affiliated with the prefectural Interior and hence were enumerated as "Interiorites" (Naichijin 内地人). The 1920 shows 55,884,992 Interiorites (males 27,980,989, females 27,904,003) -- including [15,575] Ainu (males 7,304, females 8,271). In 1924, Ainu registers were merged with general registers, as they are today, with no distinction, ending the tabulation of "Ainu" on national government population figures. Ainu populations today are estimted by various interest groups. A special "Ainu living conditions survey" (Ainu seikatsu jittai chōsa アイヌ生活実態調査) carried out in 66 municipalities (cities, towns, and villages) in Hokkaidō in 2013 sized up the lives of 16,786 people who identified as Ainu. The membership of Hokkaido Ainu Association (Hokkaidō Ainu Kyōkai 北海道アイヌ協会), an all-Ainu organization founded in 1930 -- Hokkaido Utari Association (Hokkaidō Utari Kōkai 北海道ウタリ協会) from 1961-2009 -- was about 3,200 as of this writing (2021). "Colonies" and "colonials"In 1920, Japan's policies regarding the governing of its non-Interior territories -- how far to make them more like the Interior, and whether to someday integrate them into the Interior -- were still very fluid. The point here is that the 1920 census report, as published by the Cabinet Statistics Bureau, collectively called Japan's non-Interior territories "colonies" (shokuminchi 植民地) and their register-affiliated inhabitants "colonials" (shokuminchi-jin 植民地人). At the same time, the 1920 report digested here uses "Zenkoku" (全國) -- meaning "entire country/nation" -- to refer to the prefectural Interior -- which makes sense if the other territories of the empire were regarded as "colonies". "nationality by subnationality"Notice also the order of the expression "kokuseki minseki" (國籍民籍) signifying "national register" (kokuseki) or "nationality" -- "people's register" (minseki) or what I call "territoriality" or "subnationality". This turns out to be odd, because the first breakdowns in all the tables are by "minseki" (Interiorites, Chosenese, Taiwanese, Karafutoans, South Sea Islanders) within Japanese nationality (except South Sea Islanders, who had no nationality) -- followed by foreigners (gaikokujin 外國人) broken down by nationality. Later censuses reversed the order in the table titles to "minseki kokuseki" (see 1930 census below). Volume 2Volume 2 includes the 1920 National census enforcement order (pages 13-17). The first 2 articles are as follows (pages 13-14, my transcriptions and translations).

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||