Affiliation and status in Manchoukuo

1940 Provisional People's Register Law and enforcement regulations

By William Wetherall

First posted 7 March 2021

Last updated 14 March 2021

Manchoukuo

The brief life of a state forged with strings attached

Population control

Affiliation and status

•

1940 Provisional People's Register Law

•

Prov Pop Reg Law Enforcement Regulations

•

Census

•

Sources

Manchoukuo's national languages

Multiple tongues for a multi-ethnonational state

Manchoukuo's Imperial Succession Law (1937)

Male descendants in the male line of Emperor Kangte

Related articles

Korea's 1909 People's Register Law and enforcement regulations

1872 Family Register Law: Japan's first "law of the land

Manchuria reports: Building a model railroad

Manchoukuo (Manchukuo)

The brief life of a state forged with strings attached

In the fall of 1931 -- after several decades of political football between China, Russia, and Japan over Manchuria and Korea, during which Japan acquired Russia's leasehold from China of Port Arthur and surrounding territories and Russia's South Manchuria railway operations, and annexed Korea as Chōsen -- Japan was so economically and militarily entrenched in Manchuria that the Kwantung Army was able to quickly take complete control over the territory after an incident it reportedly contrived as an excuse to take control. Some historians dub it the "Manchurian Incident", or the "Mukden Incident" after the place it occurred on 18 September 1931.

By 1 March 1932, Japan had formed a coalition of regional supporters who, on this date, issued a "Proclamation of establishment of state" (建國宣言) of Manchoukuo (滿洲國、満洲国), also written "Manchukuo" and known in Japanese as "Manshūkoku". The date was officially recorded as the 1st day of the 3rd month of Tatung (大同元年三月一日).

From 1 March 1934, the new state became "Manchoutikuo" (滿洲帝國、満州帝国) -- "Manshū Teikoku" in Japanese, and "The Empire of Manchoukuo" or "The Manchou Empire" in English. The reign name Tatung (大同 J. Daidō) was replaced by Kangde (康徳 J. Kōtoku), after which all Manchoukuo dates were reckoned from "Kangde 1-3-1" (康徳一年三月一日) -- 1st day of the 3rd month of the 1st year of Kangde, a solar calendar date corresponding to 1 March 1934 on the Gregorian calendar.

Japan's actions in Manchuria immediately incurred the wrath and displeasure of China and its many allies, including the United States and other powerful members of the League of Nations. The league censured Japan to the point that, in 1933, Japan formally left the league. Japan continued, however, to discharge its obligations under the mandate the it had received from the league to administer the South Pacific islands it had taken from Germany during World War I as a member of the Allied Powers.

Recognition politics

As commonly happens when a new state is formed through military force, established states had to decide whether to formally recognize and establish diplomatic relations with the new state. As it happened, very few states recognized Manchoukuo, and many of those that did were allied with what later became known as the Axis countries -- Japan, Germany, and Italy -- and the states Germany and Japan invaded and turned into allies.

The Soviet Union engaged with Manchoukuo short of formally recognizing it until 1940, when it signed a non-aggression pact with Japan. Some Soviet allies also, at this point, recognized Manchoukuo.

The few countries that allied themselves with Japan during the Pacific War, and those Japan "liberated" and turned into allied republics, also joined the recognition list. So, too, did the Wang Ching-wei (Wang Jingwei) regime in China that replaced, in Japan's eyes, the regime of Chiang Kai-shek, which has taken refuge in Chungking (WG Ch'ung-ch'ing, PY Chongqing). The "Provisional Government of Free India" also joined the East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere" in 1943 and recognized Manchoukuo, a fellow member.

States that recognized Manchoukuo Japan 1932-09-15 El Salvador 1934-03-03 Dominican Republic 1934 Costa Rica 1934-09-23 Soviet Union 1935-03-23 de facto Italy 1937-11-29 Spain 1937-12-02 Germany 1938-05-12 Poland 1938-10-19 Hungary 1939-01-09 Slovakia 1940-06-01 Vichy France 1940-07-12 China (Wang Jingwei) 1940-11-30 Mengkiang (Mongolia) Romania 1940-12-01 Soviet Union 1941-04-13 de jure Bulgaria 1941-05-10 Finland 1941-07-17 Denmark 1941-08 Croatia 1941-08-02 Thailand 1941-08-05 Free India The Philippines 1943 Burma

Manchoukuo today

Would Manchoukuo exist today, in 2021, if Japan had not been defeated in the Pacific War? Who can say? Any number of scenarios are possible in the fictional world of alternative history. Revolutionary Chinese communist forces might never have grown to the point of being able gain control of China, much less aid and abet the toppling of other Asian states and territories, such as the Southeast Asian countries along China's southern borders, British Hong Kong and Portuguese Macao, and Japanese Chōsen and Taiwan.

The stage for the "domino effect" that actually happened was set during the weeks straddling Japan's acceptance of the Potsdam Declaration on 14 August 1945 and its formal surrender to the Allied Powers on 2 September 1945. During the final weeks of the war, the Soviet Union broke its non-aggression pact agreement with Japan and openly sided with its European Theatre Allies, in the Pacific Theatre, and invaded and occupied Manchuria. And during the first few weeks after the surrender, the USSR -- with the blessings of the other major Allied Powers in the the Pacific Theater, inclduing the United States, United Kingdom, and the Republic of China -- occupied the northern part of Japanese Chōsen, which became the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK).

The USSR transferred control over former Manchoukuo to the Republic of China in 1946. But the region quickly became part of the staging area for the communist Chinese armies that in 1949 drove ROC's nationalist forces off the continent to the province of Taiwan, and established the People's Republic of China in Beijing.

Again, "recognition politics" raised its quarrelsome head. The world's states were immediately divided over the question of which China to recognize -- ROC, a founding member of the United Nations -- or PRC, which controlled and exercised jurisdiction over all of the China claimed by ROC except Taiwain and few islands that were parts of a coastal province. Over the next several decades, down to this writing in 2021, PRC has gradually won the recognition battle. Today, only a literal handful of the world's nearly 200 states recognize ROC. To PRC's chagrin, however, many major states, including the United States and Japan, which switched their China recognition from ROC to PRC in the 1970s, nonetheless insist that ROC has the right to political self-determination, even if that means it never formally joins PRC's political fold.

"Puppet state"

While fashionable in present-day "critical history" to write off Manchoukuo as a "puppet state" emblematic of Imperial Japan's wrongest doings, historical truth requires recognition of the fact that Japan brought a semblance of order to the region that most of the world had come to know as "Manchuria" -- a term China eschews. The region had been neglected by China, which suffered from chronic infighting between regional war lords, and pretty much left its northern borderlands to fend for themselves against Russia and Japan.

Population control

The first order of the first government of a new country, especially one born out of strife, is public order followed by nationalization. Public order -- a semblance of peace and cooperation among the people, who government or no government will go about the daily work of survival -- comes through the enforcement of laws that already exist, or are quickly proclaimed in the interest of stabilizing society. Then comes the usually long the country and stabilizing the lives of the people. , through policing. Then comes the longer process through policpolicing, which . After security comes fiscal Japan provided the muscle and organizing skills in the creation of the state of Manchoukuo on 1 March 1932. Called a puppet state by some then and by more now, Manchoukuo was nonetheless a political entity that conducted itself like a state, both with countries that formally recognized it as such, and with countries that didn't recognize it but had reason to conduct business in the country.

The government of Manchoukuo, dominated by Japanese military officers and bureaucrats, faced the problem of how to register and enumerate the population, which represented not only the so-called "five races" that comprised the new nation, but all manner of people who, in counted, might require other classifications.

This is a problem in all countries that set out to nationalize their affiliated populations in order to govern them -- protect, serve, and control them. Japan faced the same problem at the start of the Meiji period, and solved it by promulgating a national family register law in 1871, effective from 1872. Japan, partly overseeing the administration of the Empire of Korea following the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905, was instrumental in the drafting and implementation of Korea's 1909 People's Register Law (民籍法 K. Minjŏkpŏp, J. Minsekihō), which sought to achieve in Korea the same degree of demographic and political understanding and control of its affiliated population that the Family Register Law had realized in Japan.

In 1939, 7 years after its renaming -- partly fueled by the majic of the year 1940 -- a census year in the Empire of Japan and many other major countries in the world -- the year in which Japan would celebrate the 2,600 year of the founding of its imperial succession according to historical tradition -- and the year in which Tokyo would host the Summer Olympics -- Manchoukuo promulgated a Provisional People's Register Law

Aims of control

Populations are controlled in many ways for a variety of reasons. Local and national authorities are motivated to organize and oversee land distribution and usage, roads and waterways, water and fuel supplies, sewage and waste, irrigation, food production, animal breeding, markets and trade, taxes, and labor and military conscription.

The list of government concerns continues with education, all matter of health and welfare matters, elections, legislation, law enforcement, public safety and national defense, natural disaster relief, sometimes also religious and cultural affairs, and relations with other entities and governments.

The list could on and on, and would differ for every country, at every period in the country's political and social history.

Importance of control

As Japan entered the 20th century, it had unquestioned faith in its achievements. In the span of barely three decades, it had built a state that had proven capable of competing with the Euroamerican powers with which, until 1899, it had been leashed by extraterritorial treaties. Still leashed, it was victorious over China in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895. Unleashed, it defeated Russia in the Russo-Japanese war of 1904-1905. Both wars began in, and were essentially about, Korea and who would have the most say in its affairs.

All annual reports published by Japan's Residency-General of Korea during its tenure from 1907-1910 when Korea was a protectorate of Japan, and all early reports of the Government-General of Chosen that replaced it when Japan annexed Korea as Chosen in 1910, go into great detail about the failure of registration practices on the Korean peninsula, especially their susceptibility to abuse and corruption.

The governments of Chosŏ (Yi dynasty) and its successor, the Empire of Korea, attempted to improve registration practices. But attitudes of officials and others toward registration served the vested interests of fusty clans and powerful classes, rather than the proper functions of a state that aimed to develop and protect its nation of people.

Korean household registers

Korea had its own population registers and standards for keeping track of who was related to whom, and for knowing who resided where, and what land they owned, and what taxes they owed. However, practices were not uniform. Generally, registers were kept by heads of households and were mostly concerned with documenting male lineage. Wives were not necessarily included, and not everyone had a surname.

Korea's household registration system at the end of the 19th century may have been less developed, as a tool for social organization and control, than the parish registration system Japan replaced in 1871 with a comprehensive, nationwide system under local government control. By the time had become a protectorate of Japan, during and immediately after the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905, Japan had mastered the use of population registers as a tool of social control in its nationalization of older and newer territories.

Japan as protector of Korea

As a result of agreements a 1904 defense agreement and a 1905 diplomacy agreement, the Empire of Korea became a protectorate of the Empire of Japan with respect to its national defense and foreign affairs. In 1907, the Korea and Japan also signed an agreement which gave the Residency-General of Korea, Japan's protectorate government on the peninsula, the authority to oversee some of Korea's domestic administrative affairs and reforms.

The scope of the 1907 agreement gave Japan the authority to approve laws, ordinances, and administrative measures, recommend Japanese for appointments to posts within the Korean government, and approve retainments of foreigners, among other powers that amounted to significant control of Korea's domestic affairs.

Under the direction of the Residency-General, the Empire of Korea promulgated and enforced a population registration law and issued enforcement regulations. The purpose of these measures was to improving the quality of demographic information for the purpose of collecting taxes and administering other laws and policies concerning individuals and families.

This law, initiated and shaped by the Residency-General of Korea, which was overseeing many of Korea's affairs, sought to increase the precision of demographic information for the purpose of collecting taxes and introducing other administrative reforms of the kind Japan had implemented during the early years of Meiji Period.

1909 People's Register Law

On 4 March 1909, a year and a half before before its annexation to Japan, the Empire of Korea adopted, under Japanese guidance, the People's Register Law (民籍法 민적법 Minjŏkpŏp J. Minsekihō). The law, which into effect from 1 April 1909, was administered under enforcement regulations issued on 22 March 1909 by Korea's Interior [Affairs] Department. Provincial police departments, sub-provincial precincts, and local police stations with precincts were responsible for registration matters.

The 1909 People's Register Law was essentially a list of personal and family status matters that were to be reported to local registrars for recording in local population registers, and provisions for who was responsible declaring declarations, where and how declarations were to be made, and punishments for failing to report and for making fraudulent reports. Enforcement regulations stipulated which authorities had jurisdiction and responsibility for registration matters, and procedures.

Police as registrars

Police in Korea were under Korea's Interior Department, just as police in Japan were under Japan's Interior Affairs Ministry. Their involvement in population registration was not inconsistent with the scope of police duties, which embraced a number of functions that are not related to "law enforcement" in the narrower sense of preventing and solving crimes.

All manner of journalistic woodblock prints depicting and narrating true incidents in Japan during the 1870s, for example, show police protecting protecting people not only from others who might harm them or their property, but also from self-harm, as in suicide prevention (see the News Nishikie website for several examples.

Karel van Wolferen, in his chapter on Japan's police in The Enigma of Japanese Power, called them the "nurses of the people" -- by which he meant they were "nannies, monitors and missionaries" -- and he characterized imperial Japan as a "friendly neighbourhood police state" -- (van Wolferen 1992, Chapter 7, pages 181-201, Chapter 7).

Effects of new law

Shortly after the new law came into effect, the police advisory board corrected a 1907 count of households and inhabitants with information current as of 15 June 1909 (see figures below).

Between July 1909 and April 1910, again before the annexation of Korea as Chosen, Korean police, assisted by Japanese gendarmes, established uniform registers throughout the country in accordance with the new law. The new registers included wives, and everyone had a surname. The registers still reflected patriarchal and primogenitural family standards but now, in principle, also recorded the existence and status of all individuals in a household.

Perceptions of family registers

In 1909, when Japan pressured Korea to adopt Japan's highly disciplined approach to building a foundation of government on population registration, Japan was already surpassed most of its rival Euroamerican status in their ability to compile social statistics in order to facilitate their governmental missions. In the United States, which was just then completing its sea-to-shining sea continental Union, and stretching its muscles into Pacific territories like Hawaii and the Philippines, record keeping varied considerably from state to state, and territory to territory, as each was a jurisdiction unto itself, and there were few national standards.

Japan was territorially much smaller and legally less complex than the United States, and arguably it was much more easily managed as a single nation. Only a few European states, such as Sweden and France, were capable of compiling the volumes of nationwide population and other social statistics that were, by second decade of the 20th century, taken for granted in Japan.

There is a tendency, among especially Americans and others not familiar with family register practices in Japan, but also among some Japanese, to associate Japan's registration practices with Draconian social control by the state. Such criticism rarely considers the advantages of family-based registers.

In the United States, say, records of birth, death, marriage, divorce, property transactions, and all manner of other matters are mandatory under state and territorial laws and county ordinances. With its legal jurisdictions and lack of interstate standards (though such standards have been evolving), dealing with matters of inheritance, in which family heirs are scattered across the nation, can be a true challenge for an attorney who has to handle a probate or estate.

But still, in the United States, one needs to register locally in order to vote in federal, state, district, or municipal elections. And one needs a Social Security Number to do this. Historically, Social Security registration was mandated by laws related to employment, taxation, and military service. Today, though, parents are supposed to obtain a SSN for their children when born. And SSNs are increasingly used as master ID keys on all manner of public and private records. The numbers are not usually shown on official documents, but they will be recorded for database and other purposes.

For many decades in the last half of the 20th century, Japanese critics viewed US-style Social Security Numbers as a tool for the state to invade privacy, including privacy in financial affairs. Japanese balked at the adoption of a similar system for Japan.

Today in Japan, local family registers are tied together in a nationwide database. A number of local polities at first refused to participate, but now all holdouts have permitted their registers to be included.

Many national programs, facilitated through municipal or regional offices, including national health and pension insurance schemes, require linking with registers as primary records of legal existence and status. The lack of a common ID number has greatly encumbered the ability of administrative organizations to rationalize their operations, both to save operating costs, but to eliminate problems such as the inability to collate records of individuals who have migrated to another register or change their jobs or name. The National Tax Agency, which also facilitates the collection of local taxes, would also like a common ID number to improve its efficient, and to reduce tax evasion and manipulation of bank accounts and other financial matters involving the use of aliases or forms of false identity.

In other words, there is in Japan today -- as there is in many other countries -- an increasing appreciation of the value of nationwide standards in basic civil records, and the need, in the computer age, for a personal ID number that facilitates not only a host of government services -- but also protection from identity theft.

In Japan, all manner of services -- including public school enrollment, voting, national health and pension, public assistance and other forms of welfare, national and local taxes, passports and driver licences, and a host of other matters that are essential to organized life -- are facilitated by municipal registration -- family and resident registration for Japanese, and alien registration for non-Japanese residents.

Affiliation and status

Legal existence is a matter of being known in accordance with provisions of law. In Japan, one exists as an artifact of registration. Birth constitutes an event that does not exist until a birth certificate is filed and duly accepted by entry on a birth roll.

A newborn child acquires status as either a Japanese or alien. Children qualified for Japanese nationality will be entered in a Japanese family register. Those not qualified for Japanese nationality will be entered in an alien register.

Under Japanese law, such statuses have always been based on family law, which includes right-of-blood rules involving paternal or maternal lineage, as well as on right-of-relationship rules in which status is derived through marriage or adoption, but also place-of-birth or place-of-discovery rules rules that apply when finding an abandoned child of unknown parentage or nativity.

The same was essentially true for determinations of legal existence in the Empire of Korea at the time Japan annexed Korea as Chosen. There were no provisions for considerations of "race" or "ethnicity" in determining who qualified for entry in a population register. As legal statuses, being Korean and then Chosenese were civil, not racioethnic or ethnonational.

On 17 August 1899, a few months after Japan adopted its first Nationality Law, the Empire of Korea promulgated the "System of Great Korea" (大韓國制 대한국제 Tae Hanguk je). The fourth of the nine articles in this constitution of sorts outlined the duties of "Great Korea subjects" (大韓國臣民 대한국 신민 Tae Hanguk sinmin). But none of the articles defined the Korea's subjects or touched upon the topic of nationality.

Nor did Japan, when it annexed Korea on 22 August 1910, formally extend its nationality law to the peninsula. Since Korean nationality had been customarily defined, and because there were no stipulations about nationality in the annexation treaty, Japan assumed that the people who came with the territory of Korea would be subjects of Japan. In the renaming of Korea as Chosen, Koreans became Chosenese. And as Chosen was part of Japan, Chosenese naturally became Japanese subjects and nationals.

Registers as definitions of nationality

Neither Chosŏ under the Yi dynasty, nor the Empire of Korea, had a nationality law. In earlier treaties in Chinese, and in later treaties in Sino-Korean, Sinific expressions meaning "affiliation" (属) were translated into English as "nationality". Persons considered "affiliated" with Chosŏ or the Empire of Korea were "subjects" of these entities.

In customary practice, then, "nationality" was simply a matter of affiliation, and affiliation was a matter of being considered an inhabitant of the peninsula. Inhabitants were those with family ties to the native population. And as more and more, and finally most if not all inhabitants came to be formally enrolled in local population registers, enrollment in a register -- as someone with a "principle register" (本籍) in a peninsular jurisdiction -- came to be proof of being an affiliated inhabitant, hence subject, hence a national, hence a possessor of nationality.

Nationality in Japan

This was also true in Japan, which did not have a formal nationality law until 1899. China, under the Ching (Qing) dynasty, did not have formal nationality rules until 1909 -- and their main affiliation principles were based on Japan's 1899 law. China even adopted the term coined in Japan to mean "nationality" (國籍).

Not having a nationality law before 1899 did not prevent Japan from determining who was a subject. Subjects were people in Japan's affiliated household registers. And qualifications for entering and removal from such registers were governed by family law.

In fact, Japan had issued passports -- transit permits authorizing travel outside Japan, which served as identification documents when entering a foreign country -- as early as 1866, two years before the transition from the Tokugawa to Meiji governments. By 1878, the imperial government of Japan was issuing formal passport that complied with passport standards in a number of other countries.

In other words, a state does not need formal nationality laws to determine who it wishes to recognize as an affiliate of its demographic nation -- subject, national, or citizen. Japan's 1899 Nationality Law did not, in any event, declare who was considered to already be Japanese. Japanese were already Japanese. Similarly, Taiwanese and Karafutoans were already Japanese when Japan applied its nationality law to these two territories in respectively 1899 and 1924.

Japan's Nationality Law merely codified rules which, for decades and even centuries, had determined who qualified for entry in a family register affiliated with a locality in Japan's jurisdiction. What was new about the law was its provisions for naturalization, and other auxiliary rules for gaining, losing, and recovering status as Japanese other than at time of birth -- and rules which restricted naturalized persons from holding higher political and military posts.

The 1909 People's Register Law continued to operate, in conjunction with statue and customary family law, to determine who qualified for status in a Chosen "principle register" (honseki). And status in such a register continued to determine who was "Chosenese". Since Chosen was part of Japan's sovereign dominion, it stood to reason that Chosenese were subjects of Japan, and as subjects of they Japan they were obviously its nationals, and as its nationals they were obviously Japan. I say "obviously" because that is how such status matters would be customary regarded -- without the need for a specific law to spell out the "obvious" consequences of Korea having become Chosen.

Like registers in the prefectures of the Interior, and in Taiwan and Karafuto, registers in Chosen defined the population that constituted the subnational territory of Chosen within the greater Japanese nation. Anyone in a Chosen register was Japanese by nationality and Chosenese by subnationality.

"Minseki" in Japanese usage

The term "minseki" (民籍) was an older Chinese term for population (affiliate) registration. The term had also been used in Japan long before it was pressed into service in the 1909 Korean law.

"Minseki" (民籍) was used to refer to registers at the time the first national Family Register Law as promulgated in 1871. Moreover, the expression "jinmin koseki" (人民戸籍) appears in the 1871 law. My hunch -- which I am unable to substantiate at this time -- is that "minseki" is a reduction of "jinmin koseki" -- at least in cases when the "people" (jinmin 人民) were enrolled in registers by household (戸籍), which generally referred to a dwelling with an address.

See Minseki in the article on the 1872 Family Register Law under "Nationality".

During the 1930s, Japan published national census figures in terms of "minseki kokuseki betsu jinkō" (民籍国籍別人口) meaning "Population by minseki/kokuseki" -- in which the terms "minseki" (民籍) and "kokuseki" (国籍) were conflated. "Minseki" embraced Interiorites (内地人 Naichijin) and Exteriorites (外地人 Gaichijin), and Exteriorites were broken down by Chōsen (朝鮮), Taiwan (台湾), and Karafuto (樺太 (Karafuto). Then came "aliens" (外国人 gaikokujin), broken down by, for example, Republic of China (中華民国 Chūka Minkoku), followed by many other countries.

For an example of territorial population statistics by "minseki" in the Empire of Japan, see Minseki in the article on the 1872 Family Register Law under "Nationality".

Interiorization of Chosen register laws

From 29 August 1910, when Korea was incorporated into Japan as Chosen, the Residency-General of Korea became the Government-General of Chosen. Over the next three decades, GGC introduced Interior registration rules in order to make Chosen's family registers more those the prefectures.

Family law was at the heart of civil status in Japan, and family registers were the principle instruments by which the state and local polities enforced national and local laws and ordinances to carry out their governmental missions. Registers played the name role in the nationalization of Korea as Chosen in 1910 as they had in all territories Japan had previously incorporated into its sovereign empire -- from Ezo (Hokkaido) in 1869, Ryukyu (Okinawa) in 1872, Ogasawara in 1875, the Kuriles (and some extent natives of Karafuto) in 1875, Formosa (Taiwan) in 1895, and Karafuto in 1905.

First Korean nationality Law

The Republic of Korea, founded on 15 August 1948, was the next to last East Asian state to formally adopt a principle of ambilineality in its nationality law. Not until 1998 did ROK revise its 1948 Nationality Act to enable a child to acquire ROK's nationality at time of birth if either of its parents was a national. Until then, the Nationality Act had been, like many of ROK's laws, a bastion of patriarchy. The Republic of China did not adopt ambilineality until 2000.

ROK was not exceptional in its adoption of a patrilineal right-of-blood principle in 1948. The principle had been, and was then still, the most common nationality standard in the world. Only during the second half of the 20th century did most states, having ratified the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), begin to adopt ambiliniality.

By the time ROK was founded in 1948, its provisional government had already reversed many of the changes the Government-General of Chosen had imposed on Korean family law, in particular provisions for use of the same family name in a register as opposed to different surnames, and Japan's more permissive rules about marriage and adoption. However, ROK adopted a Family Register Law that continued to essentially enforce the same concept of population registration as a tool for bureaucratic control.

After considerable pressure for more liberal rules concerning marriage and other family matters, ROK has more recently revised its laws to permit, for example, marriages between people with surnames of the same clan -- though Korean individuals and families are free to follow customary practices of avoiding same-clan surname marriages.

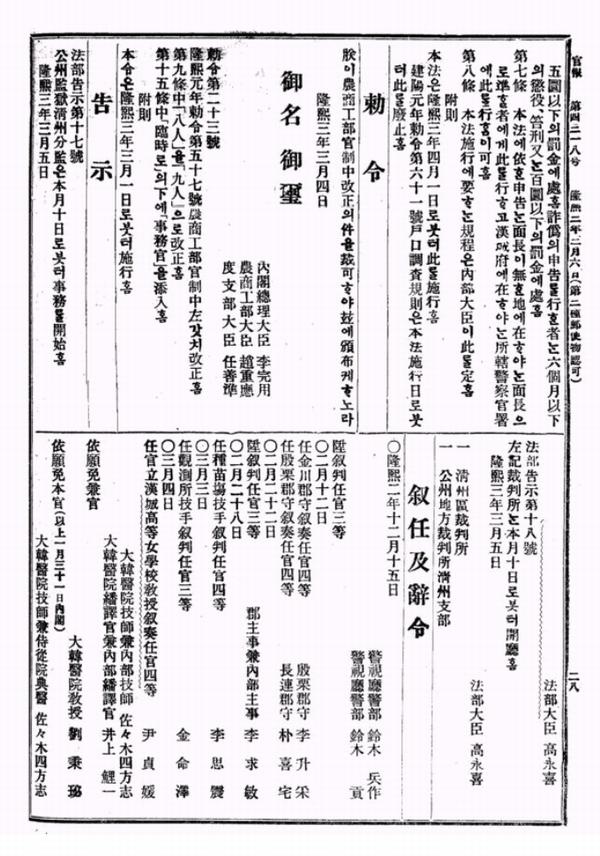

1909 People's Register LawAs early as February 1909, the government of the Empire of Korea, and the Residency-General of Korea representing the government of Japan in Korea, were initiating the the imperial sanctioning and promulgation of the People's Register Law. The law was sanctioned and promulgated by the Emperor of Korea on 4 March 1909 and signed by Korea's Prime Minister of the Cabinet, Minister of Interior, and Minister of Justice. The new law was published in Korea's Official Gazette (官報 Kwanbo) on 6 March 1909 (Kwanbo, Number 4318, pages 17-18, see images to the right). A supplementary provision stipulated that the law would come into effect from 1 April 1909. Another supplementary provision stipulated the Interior [Home] Department would determine enforcement rules. The Interior Department issued People's Register Law Enforcement Regulations in a directive dated 22 March 1909. The Korean and Japanese texts of both the law and regulations are shown below, with my structural translations and commentary. |

||||

|

1909 People's Register Law With commentary on terminology |

|||

Korean textThe Korean text is my adaptation from an electronic version posted on the website of the Kyujanggak Institute For Korean Studies at Seoul National University. I converted standard hangul and non-JIS hanja into Unicode. Seven non-standard hangul I was unable to encode are highlighted here as H1 to H7, numbered in the order of their appearance. I have vetted the Korean text against the text of the law as published in the Kwanbo or Official Gazette" of the Empire of Korea, using images found on a blog, which also shows a Japanese version (see next). Japanese textThe Japanese text is something I created by editing the Korean text into the Japanese versions as represented in Japanese materials I obtained from the Japan Center for Asian Historical Records (JACAR) (アジア歴史資料センター Ajia Rekishi Shiryō Sentaa) [Asia history materials center] at the National Archives of Japan (NAJ) (国立公文書館 Kokuritsu Kōbunsho Kan) [National public document repository]. I have added a comma or two that seems to have been intended but dropped, and noted a couple of inconsistencies in kana usage, in red highlighting. English translationThe structural English translation is mine. I have chosen to translate the Japanese rather than the Korean version because I am unable to represent the older hangul and am not familiar with historical hangul orthography (though at the phrasal level the Korean expressions are clear). See more about the linguistic and graphic characteristics of the two versions under "Note on linguistic characteristics" in the "Sources" section below. CommentaryI have highlighted in green the terms on which I have glossed in boxed commentary following my translations. SourcesSee Sources below for full particulars on the Japanese materials used to confirm both the Korean and Japanese texts of the 1909 population law and enforcement regulations, and for comments on Korean texts were treated in Japanese materials. |

|||

|

民籍法 (민적법) People's Register Law |

|||

|

官報 第四千三百十八號 隆熙三年三月六日 土曜 內閣法制局官報課 法律 朕이民籍法을裁可H1야玆에頒布케H1노라 朕帝国議会ノ協賛ヲ経タル国籍法ヲ裁可シ茲ニ之ヲ公布セシム隆熙三年三月四日 御名御璽 內閣總理大臣 李完用 法律第八號 民籍法 |

Official Gazette Number 4318 6 March 1909 (Yunghŭi 3-3-6) Saturday Cabinet Legislative Bureau Statute I [the emperor] sanction the People's Register Law and herein distribute [promulgate] it. 4 March 1909 (Yunghŭi 3-3-4) Imperial seal Prime Minister of the Cabinet Yi Wan Yong Law Number 8 People's Register Law |

||

PersonaYi Wang Yong (李完用 1958-1926) advocated that Korea be developed like Japan and this led him, as the Education Minister, to promote and sign the 1905 treaty under which Korea became a diplomatic protectorship of Japan. Yi became Korea's Prime Minister in 1906, and as such he also signed both the 1907 treaty which allowed Japan to play a direct role in Korea's domestic legal reforms, and the 1910 treaty that joined (annexed) Korea to Japan. He heads the list of "collaborators" compiled by the government of the Republic of Korea under a 2005 law which allows the state to return to its ownership property of "pro-Japan anti-[racioethnic]-nation actors" (친일반민족행위자 ch'inil panminjok haengwija 親日反民族行為者). Pak Che Sun (朴齊純 1858-1916 Park Che Soon) signed the 1905 diplomatic protectorship treaty as Foreign Affairs Minister, and he too is on ROK's collaborator list. Ko Yŏng Hŭi (高永喜 1849-1916 Ko Young Hee) was also one of the several young Korean officials who, after the Japan-Chosen amity treaty of 1876, was sent to Japan to observe its development, and he advocated a similar path for Korea. Over the next three decades Ko spent more time in Japan, including a stint in 1903 as Korea's minister extraordinary and plenipotentiary to Japan. He, too, is officially regarded as a traitor and collaborator in ROK. After Korea joined Japan as Chosen, all three of the above officials, among many others, received titles as nobility under the Chosen Nobility Order (朝鮮貴族令 Chōsen kizoku rei), established in 1910 pursuant to Article 5 in the annexation treaty. |

|||

|

第一條 左記各號의一에該當H2境遇에在H1야H3其事實發生日로븟터十日以內에本籍地所轄面長에게申告H4이可H4但事實의發生을知H1기不能H2時H3事實을知H2日로붓터起算홈

前項의事實로二面長以上의所轄에涉H1H3時H3申告書各本을作H1야申告義務者의所在地所轄面長에게此H5申告H4이可홈 |

第一條 左記各號ノ一ニ該當スル場合ニ於テハ其事實發生ノ日ヨリ十日以內ニ本籍地所轄面長ニ申告スヘシ但シ事實ノ發生ヲ知ルコト能ハサルトキハ事實ヲ知リタル日ヨリ起算ス

前項ノ事實ニシテ二面長以上ノ所轄ニ涉ルトキハ申告書各通ヲ作リ申告義務者ノ所在地所轄面長ニ之ヲ申告スヘシ |

||

|

Article 1 In cases corresponding to any one of the items to the left [the following items], within ten days from the day of the occurrence of the matter, [the matter] should [must] be declared [reported] to the head of the town with jurisdiction [over] the principle register place [locality, address]. However, when it has not been possible to know the occurrence of the matter, calculation will be from the day the matter was known.

When a matter in the preceding paragraph involves two or more town jurisdictions, [the declarant / reporter] should make copies of the declaration [report document] for each [jurisdiction], and declare [the matter] to the head of the town with jurisdiction over the place [locality] in which the person with the duty to declare is [exists, lives, resides].

|

|||

|

第二條 第一條의申告義務者H3左와如홈

前項境遇에在H1야戶主가申告H6行H4이能치못H2時H3戶主H6代H7主宰者.主宰者가無H2時H3家族又H3親族.家族又H3親族이無H2時H3事實發生H2處所又H3建物等을管理H1H3者或은隣家에셔申告H6行H4이可홈 |

第二條 第一條ノ申告義務者ハ左ノ如シ

前項ノ場合ニ於テ戶主カ申告ヲ行フコト能ハサルトキハ戶主ニ代ハルヘキ主宰者、主宰者ナキトキハ家族又ハ親族、家族又ハ親族ナキトキハ事實發生ノ場所又ハ建物等ヲ管理スル者若ハ隣家ヨリ之ヲ爲ス可シ [> スヘシ] |

||

|

Article 2 Persons with duty of declaration under Article 1 are as to the left [as follows].

In the cases of the preceding paragraph, when the head of household is unable to carry out the declaration, the person who ought to be the presider in lieu of the head of household; when there is no presider, a family member or relative; when there is no family member or relative, the person who manages the place or building et cetera [where] the matter occurs; or a neighboring family, should effect this [declaration]. |

|||

|

第三條 婚姻.離婚.養子及罷養의申告H3實家戶主의連署로써行H4이可H4但連署H6得H1기能치못H2時H3申告書에其旨H6附記H4이可홈 |

第三條 婚姻、離婚、養子及罷養ノ申告ハ實家ノ戶主ノ連署ヲ以テ之ヲ爲スヘシ但シ連署ヲ得ルコト能ハサルトキハ申告書ニ其旨ヲ附記スヘシ |

||

|

Article 3 Declarations of marriage, divorce, adoption and ending adoption should be effected with the joint signatures of the actual families. However when it is not possible to obtain joint signatures the reason should be noted on the declaration. |

|||

|

第四條 第二條의申告義務者가本籍地以外에居住H1 H3境遇에在H1야H3其居住地所轄面長에게申告H4을得홈 |

第四條 第二條ノ申告義務者ハ本籍地以外ニ居住スル場合ニ於テハ其居住地所轄面長ニ申告スルコトヲ得 |

||

|

Article 4 In cases [when] the person with the duty of declaration under Article 2 resides in [a locality] other than the principle register locality, [the person] can declare to the village head with jurisdiction over the residence locality. |

|||

|

第五條 民籍에關H2申告H3書面으로써行H4이可H4但現今間은口頭로써行H4을得홈 |

第五條 民籍ニ關スル申告ハ書面ヲ以テ之ヲ爲スヘシ但シ當分ノ內口頭ヲ以テスルヲ得 |

||

|

Article 5 Declarations concerning population registers are to be effected in writing. However, for the present they may be made orally. |

|||

|

第六條 第一條의申告H6懈怠히H2者H3五十以下의笞刑又H3 五圜以下의罰金에處홈詐僞의申告H6行H2者H3六個月以下의懲役笞刑又H3百圜以下의罰金에處홈 |

第六條 第一條ノ申告ヲ怠ル者ハ五十以下ノ笞刑又ハ五圜以下ノ罰金ニ處ス詐欺ノ申告ヲ爲シタル者ハ六ヶ月以下ノ懲役笞刑若ハ百圜以下ノ罰金ニ處ス |

||

|

Article 6 A person who neglects [fails] [to make] the declaration of Article 1 will be punished with lashing of up to 50 [lashes] or a fine of up to 5 hwan [J. yen]. However, a person who effects a fraudulent declaration will be punished penal servitude of up to six months and lashing or a fine of up to 100 hwan.

|

|||

|

第七條 本法에依H2申告H3面長이無H2地에在H1야H3面長으로準H7者에게此H6行H1고漢城府에在H1야H3所轄警察官署에此H6行H4이可홈 |

第七條 本法ニ依ル申告ハ面長ナキ地ニ於テハ面長ニ準スヘキ者ニ之ヲ爲シ漢城府ニ於テハ所轄警察官署ニ之ヲ爲スヘシ |

||

|

Article 7 Notifications pursuant to this law, in localities without a village head, should be made to a person who is equivalent to a village head, and in Hansŏng province should be made to the police headquarters with jurisdiction.

|

|||

|

第八條 本法施行에要H1 H3規程은內部大臣이此H6定홈 |

第八條 本法施行ニ要スル規程ハ內部大臣之ヲ定ム |

||

|

Article 8 Rules required for enforcement of this law shall be determined by the Minister of the Interior [Home] Department. |

|||

|

附則 本法은隆熙三年四月一日로붓터此H6施行홈 建陽元年勅令第六十一號戶口調査規則은本法施行日로붓터此H6廢止홈 |

附則 本法ハ隆熙三年四月一日ヨリ之ヲ施行ス 建陽元年勅令第六十一號戶口調査規則ハ本法施行ノ日ヨリ之ヲ廢止ス |

||

|

Supplementary provisions This law shall be enforced from the 1st day of the 4th month of the 3rd year of Yunghŭi [1 April 1909]. The Population [door-mouth] Survey Regulations, Imperial Ordinance No. 61 of the 1st year of Kŏn'yang [1896 -- ], shall be abolished [abrogated] from the day of enforcement of this law.

|

|||

|

1909 Pop Reg Law Enforcement Regulations Local police to oversee population registration |

||

Korean textForthcoming. Japanese textThe Japanese text reflects a transcription in present-day graphs with katakana and punctuation, which I cut and pasted from the "dreamtale" blog (see note above), then slightly reformatted and corrected. English translation, Commentary, SourcesSee People's Register Law (above). |

||

|

民籍法執行心得 (민적법 집행 심득) People's Register Law Enforcement Regulations |

||

|

第1条 |

第1条 民籍に関する事項を記載する為め、警察署、警察分署及巡査駐在所に民籍簿を備ふ。 民籍法第1条各号の事実発生に依り民籍簿より除きたるものは、面別に編綴して除籍簿とす。 |

|

|

Article 1 For the purpose of recording particulars concerning population registers, [provincial] police departments, police branch departments [precincts within provincial departments], and constable-resident-places [local substations within precincts, at which a police officer resided] shall keep [maintain] population register records. As for what [the family records] [officials] have removed [struck] from population register records due [pursuant] to the occurrence of a matter in each item [the items] of Article 1 of the People's Register Law, the town (面 myŏ) shall separately compile and bound [them] [and] regard [them] as removed [struck] registration records. |

||

|

第2条 |

第2条 民籍には、地名及戸番号を付すべし。 |

|

|

Article 2 On population registers, [registrars] are to put the name of the lot and the number of the household. |

||

|

第3条 |

第3条 民籍記載の順位は左の如し。

妾は妻に準ず。 |

|

|

Article 3 The order of population registration recordings shall be as to the left [as follows].

A mistress shall be equivalent to [be recorded in the same manner as] a wife. |

||

|

第4条 |

第4条 棄兒発見の場合には、一家創立として取扱ふ可し。但し、養子として収養せんとする者あるときは、一家創立の上養子の取扱を為し、又扶養者あるときは其附籍として取扱ふべし。 |

|

|

Article 4 In the case of finding an abandoned child, [the registration] should be treated as the establishment of [by establishing] a [new] family. However, when there is someone who would adopt [accept and foster] [the child] as an adopted [fostered] child, [police] are to effect treatment [as that] of an adopted child on top of [in addition to] establishing a [new] family; or when there is a supporter [someone who will assist and foster (the child)] [then] [the child's register] is to be treated as an attached register [register attached to the supporter's register].

|

||

|

第5条 |

第5条 一家絶滅したる場合は、其旨を記載して除籍すべし。 |

|

|

Article 5 In a case in which a family has ceased to exist, it shall be removed from the registry recording the reasons [for its extinction]. |

||

|

第6条 |

第6条 附籍者の民籍は、一家族毎に別紙を以て編成し、附籍主民籍の末尾に編綴すべし。 附籍者の民籍には、附籍主の姓名及其附籍なる旨を欄外に記載し置くべし。 |

|

|

Article 6 The population register of an attached-registrant should be compiled as a separate sheet for each family clan and be bound at the end of the population register of the head of the attached-register. To the population register of the attached-registrant should be recorded in the margin the name [surname and personal name] of the head of the attached-register and the purport [purpose] of the attached-register. |

||

|

第7条 |

第7条 面長は常に部内の民籍異動に注意し、申告を怠る者あるときは之が催告を為すべし。 |

|

|

Article 7 The village head should always be alert to population register changes within [his] department [jurisdiction], and when there is a person who neglects [fails] [to make] a declaration [he] should make a notification [warning] [to do so]. |

||

|

第8条 |

第8条 面長は民籍法第1条の申告書を取纏め、其月分を翌月15日迄に所轄警察官署に送致すべし。 |

|

|

Article 8 The village head should collect the declarations of Article 1 of the People's Register Law, and by the 15th day of the month following the month [in which the declarations are made] [he] should send [them] to the police headquarters with jurisdiction. |

||

|

第9条 |

第9条 警察官署に於て受けたる申告書中、他管に係るものは、所轄警察官署に送致すべし。 |

|

|

Article 9 Among declarations that have been received by a police headquarters, those related to other administrations [jurisdictions] should be sent to the headquarters with jurisdiction. |

||

|

第10条 |

第10条 民籍簿は甲号様式、口頭申告書は乙号様式に依り調製すべし。 |

|

|

Article 10 [Police headquarters] should prepare population register records in accordance with Form A, and Oral Declarations in accordance with Form B. |

||

First census under People's Register Law

Within three months after the new registration law came into force, a 1907 estimate of Korea's population was revised using information from a mid-June 1909 survey. The first census conducted under the new law was completed by May 1910.

15 June 1909 estimates

Shortly after the People's Register Law was enforced, the Police Advisory Board augmented 1907 household and head counts with records compiled as of 15 June 1909.

Source

The population figures introduced here are from the following source, scans of which are available on the Japan Center for Asian Historical Records (JACAR) (アジア歴史資料センター Ajia Rekishi Shiryō Sentaa) [Asia history materials center] at the National Archives of Japan (NAJ) (国立公文書館 Kokuritsu Kōbunsho Kan) [National public document repository].

元警務顧問部調査

韓国戸口表

四十三年六月十五日記録一部受Former Police Advisory Department survey

Korea Household and Population tables

Partially subject to 15 June 1910 recordsJACAR Reference code B03041515500

Reel No. 1-0464

The above publication is represented as having come by way of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Images include a cover with the titling as shown. Inside the cover is a brief undated preface. The main body of the report consists of 28 numbered pages of tables showing population breakdowns by police stations within police precincts within provincial police department jurisdictions. There is a blank back cover but no colophon.

Preface

According to the preface, the figures in the tables were based on households (戸口) surveyed in 1907 (Kwangmu 11) by the Former Police Advisory Department [Board], corrected with data compiled as of 15 June 1909 by police at stations in precincts in the jurisdiction of the Metropolitan Police Agency (警視庁) [headquarters department] and in the jurisdictions and 23 provincial (道) police departments. The 1909 survey was conducted by police pursuant to the People's Register Law enforced from 1 April 1909.

Statistics

The figures are broken down by number of households (戸数) [number of doors] and people (人口) [people's mouths] by three statuses -- Korean (韓人 Kanjin), Japanese (日本人 Nihonjin), and Other aliens (其他外国人 Sono hoka no gaikokujin).

The use of "Korean" and "Japanese" reflects the fact that at the time (1907 and 1909), Korea had not joined (been annexed to) Japan as Chosen, and Koreans had not yet become Japanese of Chosenese "minseki" (population register) status. Japanese are therefore "aliens" in Korea -- though of somewhat different status than "Other aliens" since the Empire of Korea had formally become a protectorship of the Empire of Japan in 1905.

Population of the Empire of Korea

15 June 1909 adjustments of 1907 census

Households and inhabitants by nationality

Koreans, and Japanese and other aliensHouseholds People People / [doors] [mouths] Household Koreans 2,330,358 10,222,829 4.39 [Kanjin] Japanese 43,983 145,219 3.30 [Nihonjin] Other aliens 2,310 10,312 4.46 [Sonota no gaikokujin] Total 2,376,651 10,378,360 4.37The figures for Households and People for

the three nationality statuses are as published in

Kankoku kokōhō (see above).

The People/Household ratios and Totals are my mine.

10 May 1910 census

It took the Empire of Korea a few months longer than expected to conduct the first census under the new registration law. The survey planned for completion by the end of 1909 could not be finished until May 1910. The tally of aliens in Korea, however, appears to have been completed on schedule.

There are full accounts of the two surveys in Japanese and Korean versions of the annual reports begun by the Residency-General of Korea and continued by the Government-General of Chosen. Here I have cited the full description of the 1909-1910 census as reported in the English version.

The Third Annual Report on Reforms and Progress in Korea (1909-10)

Compiled by Government-General of Chosen

Seoul, December 1910

xiii, 194 pages, plates and maps

Elibron Classics facsimile, 2005, softcoverSee Korea, Chosen, and Tyosen reports for details on this series of reports.

The census of the "Native Population" as of 10 May 1910, and the count of aliens as of the end of 1909, are described as follows (pages 15-17, [bracketed clarifications] and underscoring mine).

|

5. New Census of Population As alluded to in the last Annual Report, the work of taking the census, heretofore conducted by the Urban Prefects and District Magistracies, was, in February of 1908, transferred to a Census Section under the control of the Police Affairs Bureau of the Home [Interior] Department, and the local police authorities were charged with this matter. In March of 1909, new regulations [People's Register Law and enforcement regulations] were promulgated, by which the methods of investigating and taking the census were indicated, said regulations going into force on and after the first of April. But the taking of the new census was commenced at different times according to the judgment of the provincial Chief Police Inspectors, having regard to the local conditions of their respective provinces. Thus some provinces commenced in July or August and others in September; while the completion of the new census was hoped for by the end of December. [Japanese] Gendarmes also participated in taking the census in districts covering one-third of the whole country. The police authorities and gendarmes in some districts, however, being compelled to engage in putting down insurgents and in stamping out cholera, could not complete the taking of the new census until May of the next year. The return of the new census shows native population and dwelling houses according to provinces as seen in the following table:--

On May 10th, 1910

No. of Native Population

Province dwellings Male Female Totals

_________________________________________________________

[ Provincial data omitted here ]

_________________________________________________________

Grand totals 2,742,263 8,862,650 6,072,832 12,934,282

Thus the total population of Korea, according to the new census taken in May, 1910, amounts to 12,934,282 and the total of dwelling houses to 2,742,263. Compared with the census taken in 1907 by the "Advisory Police Board," there is an increase of 3,178,309 in population and of 408,351 in dwellings. Such a difference is due chiefly to the fact that the census taken in 1907 did not include the whole of the population and dwellings in the extreme interior of the northern provinces and also in small islands where the police authorities had little opportunity to investigate. In the taking of the new census, 49,888 yen was spent in 1909 and 3,000 yen in 1910, thus making a total of 52,888 yen. After the completion of the new census, each police station was provided with registration books for population and dwellings in its jurisdictional district. Inhabitants are required to report to their Village Head-man as to their occupation, status, movements and change of residence, verbally or in writing (in the case of the city of Seoul the inhabitants are required to report direct to Police Stations); and the Headmen are required to transmit within fifteen days all such reports for each month to the Police Station concerned. Based on the reports submitted, the police authorities review the census registers every five years. The number of Japanese and foreign nationals residing in Korea at the end of December 1909 is shown in the following table:--

(At the end December, 1909.)

Number of Population

Nationalities Male Female Total

___________________________________________________

Japanese 79,947 66,200 146,147

Chinese 9,163 405 9,568

American 271 222 493

English 86 73 159

[ Other nationalities omitted here ]

[ Fewer than 100 -- French, German, Russian,

Greek, Canadian ]

[ Fewer than 10 -- Norwegian, Italian, Australian,

Portuguese, Belgian ]

___________________________________________________

Totals 89,619 66,955 156,574

1908 80,186 56,709 136,895

|

Because the above report was published after the annexation, it was issued as a compilation of Government-General of Chosen. However, the report concerns mostly matters before the annexation, and hence makes attempts to make clear terminological distinctions between pre- and post- annexation usage.

The Japanese population appears to be sexually fairly well balanced. However, a note in the Japanese edition of this report, published in March 1911, states in an overview of "Korea's population registration affairs [administration]" (韓国の民籍事務 Kankoku no minseki jimu), that "Japanese military personnel stationed in Korea are not included in the numbers of Japanese" (pages 22-23).

The Chinese population is predominantly male. The American, British, and German populations have nearly as many females as males. The French population is largely male, there are more Australian and Canadian women than men.

Nomenclature

The above statistics, concerning population surveys taken before 29 August 1910, when Korea was annexed to Japan as Chosen, reflect the following terms in Japanese reports (romanizations and translations mine).

韓人 Kanjin > Korean

日本人 Nihonjin > Japanese

其他外国人 Sonota no gaikokujin > Other aliens

Statistics published after the annexation reflect the fact that Korea had become Chosen and Koreans had become Chosenese. Since Chosenese were now Japanese, "Japanese" formally embraced all people in population registers affiliated with parts of Japan's sovereign dominion -- Interiorites (prefectural affiliates), Taiwanese (Taiwan affiliates), Karafutoans (Karafuto affiliates), and Chosenese (Chosen affiliates).

内地人 Naichijin > Interiorites

朝鮮人 Chōsenjin > Chosenese

外国人 Gaikokujin > Aliens

Interiorites were generally listed first in demographic and vital statistics related to Chosen.

There is considerable variation in usage in official English reports, some of which speak of "Koreans" and "Japanese" long after Japanese reports were consistently speaking only of "Chosenese" and "Interiorites". In other ways, too, the "Empire of Japan" is apt to be seen differently through English than in Japanese.

Today, many Japanese writers, while referring to affiliates of Chosen as "Chosenese" (朝鮮人 Chōsenjin), refer to affiliates of the Interior as "Japanese" (日本人 Nihonjin). Many Korean writers, especially in the Republic of Korea, prefer "Koreans" (韓国人 Kankokujin) to "Chosenese".

For more about how statistics were reported by the Residency-General of Korea (RGK) and the Government-General of Chosen (GGC) before and after the annexation, in Japanese, see the "Korea and Chosen publications" section of Chosen: The legal integration of Korea.

For more about how statistics were reported in English versions of RGK and GGC reports, and in other English publicity materials, see "Korea, Chosen, and Tyosen reports" in The Empire in English feature of this website.

People's Register Law sources

The following sources provide insights into how and how not to understand Manchoukuo's 1940 Provisional People's Register Law and its enforcement.

Edwin G. Beal represents a wartime effort to monitor Manchoukuo's effort to classify and enumerate its population according to nationality and other statuses.

Mariko Tamanoi provides a lot of information but leans toward a racialist understanding of nationality and territoriality not supported by legal facts.

Endō Masataka (遠藤正敬 b1972) has made more sense of Imperial Japan's nationality and household register laws than most other writers. His understanding of their essential territoriality is reflected in his analyses of the purposes and workings of Manchoukuo's People's Register Law.

Beal 1945

Edwin G. Beal, Jr.

The 1940 Census of Manchuria

The Far Eastern Quarterly (Association for Asian Studies)

Vol. 4, No. 3 (May 1945)

Pages 243-262 (20 pages)

Readable through www.jstor.org.

This article is especially interesting as an example of the ability of interested parties in the United States to monitor developments within Manchoukuo during the Pacific War. Copies of many official publications of enemy states continued to find they way into the hands of intelligence officers and academics.

Manchoukuo, as an ally of Japan, formally declared war on the United States on 8 December 1941. Thailand joined Japan's aggressions against the United States and Great Britain on 25 January 1942. Wang Ching-wei's National Government of China formally declared war on the US and GB on 9 January 1943, as did Burma and the Philippines on respectively 1 August 1943 and 23 September 1944.

Tamanoi 2000

Mariko Asano Tamanoi

Knowledge, Power, and Racial Classification:

The "Japanese" in "Manchuria"

The Journal of Asian Studies (Association for Asian Studies)

Vol. 59, No. 2 (May 2000)

Pages 248-276 (29 pages)

Readable through www.jstor.org.

Abstract

Mariko Asano Tamanoi explores the fixity and fluidity of racial and national categories that emerged in the process of Japanese colonization of Manchuria in the 1930s and 1940s. She concentrates in particular on the "officializing" practices and procedures that the "Japanese" agents of colonization pursued in classifying the different "races" and peoples inhabiting this northeast region of China. The author argues that Japanese colonial racism defined in the Japanese empire -- and continues to define in contemporary Japan -- "Japanese" and "Japaneseness" in complex and even contradictory ways.

Mariko Tamanoi, a research professor of anthropology at the University of California in Los Angeles, describes herself as a " historical-anthropologist who is interested in the fates of ordinary people in wars", and as a "sociocultural "(2021-03-18). Her interests sociocultural anthropology, historical anthropology, and the "history of the present" meaning "history as a complex interaction between the past and the present".

This article is every bit as misleading as the abstract.

Tamanoi 2005

Mariko Asano Tamanoi (editor)

Crossed Histories: Manchuria in the Age of Empire

Association for Asian Studies

University of Hawaii Press, 2005

216 pages, hard cover, dust jacket

Japanese edition published in 2008 (below).

Endō 2007

遠藤正敬

満洲国草創期における国籍創設問題:

複合民族国家における「国民」の選定と帰化制度

早稻田政治經濟學誌

No. 369,2007年10月

ページ143-161

Endō Masataka (b1972)

Manshū sōsō-ki ni okeru kokuseki sōsetsu mondai

(Fukugō minzoku kokka ni okeru "Kokumin" no sentei to kika seido)

[ Nationality foundation problem in Manchoukuo early period ]

[ (Determination of "nationals" and naturalization system in composite [racioethnic] nation Manchoukuo) ]

Waseda seiji-keizai-gaku shi

[ Waseda Journal of Political Science and Economics ]

No. 369,October 2007

Pages 143-161

A pdf edition of this article can be downloaded through Waseda University Repository (早稲田大学リポジトリ).

The author's profile states that he left his studies at Waseda University [Graduate] School of Political Science upon the completion (expiration) of the term of [his] doctoral program in the school.

Tamanoi 2008

玉野井麻利子(編)

山本武利 (監訳)

満洲:交錯する歴史

東京:藤原書店

2008年2月1日

350ページ、単行本

Tamanoi Mariko (editor)

Yamamoto Taketoshi (supervising translator)

Manshū: Kōshaku suru rekishi

[ Manchoukuo: Histories that cross and mix ]

Tokyo: Fujiwara Shoten

1 February 2008

350 pages, hardcover, jacket, obi

Japanese edition of Tamanoi 2005 (above).

Endo 2010

遠藤正敬

満洲国における身分証明と「日本臣民」:

戸籍法、民籍法、寄留法の連繋体制

アジア研究

2010年、56巻、3号

ページ1-11

Endō Masataka (b1972)

Manshūkoku ni okeru mibun shōmei to "Nihon shinmin"

(Kosekihō, Minsekihō Kiryūhō no renkei taisei)

[ Status certification and "Japan subjects" in Manchoukuo ]

[ (The linkage system of the Family Register Law, People's Register Law, and Residence Law) ]

Ajia kenkyū

[ Asia studies ]

2010, Volume 56, Number 3

Pages 1-11

A pdf edition of this article can be downloaded through J-Stage (JST) [Japan Science and Technology Agency).

Manchoukuo's national languages

Multiple tongues for a multi-ethnonational state<

Manchoukuo's Imperial Succession Law (1937)

Male descendants in the male line of Emperor Kangte

Having become a new state predicated on the notion of an ethnonational coalition of 5 major ethnonational peoples (zoku 族) in 1932, and having been organized as a constitutional monarchy in 1934 under the presumptive successor of the Manchu dynasty dethroned upon the founding of the Republic of China in 1912, Manchoukuo needed a law that established clear rules for determining who would follow in what was foreseen as an eternal succession of Manchu imperial family descendants.

The problem was that, as in Japan until the reign of the contemporary Emperior of Japan Hirohito, who had only a wife and no consorts, Emperor Kangte -- better known as Puyi -- had a succession of wives and consorts, who were secondary wives -- there being one principle wife.

In 1937, when the succession law was pomulgated, Puyi married his 3rd wife, a Manchu woman, who like his first 2 wives, were decorative, but she died in 1942. He had married his first 2 wives -- a principle wife and a consort -- in 1922. He appears to have not gotten along with them, nor they with each other. And it seems that he himself was not especially interested in cultivating a real empress.

Before marrying his 3rd wife in 1937, there was talk about him marrying a Japanese woman. That same year, his youngest brother Pujie (溥傑 1907-1994), had married Saga Hiro (嵯峨浩 1914-1987), the daughter of a noble Japanese family. See 1937 Fuketsu and Hiro on the "Couples 1" page in the "People" section of the "Konketsuji" website for details.

Puyi married his 4th wife, a Han woman, in 1943, who understook her education in Manchoukuo.

Japan invaded China the year of Puyi's 3rd marriage in 1937, and within a year Japanese forces controlled large parts of northern China south of Manchoukuo, and much of eastern China along the coast. In 1937, the nationalist government of the Republic of China, which had been at Nanking (Nanjing), fled to Chungking (Chongqing), from which its leader, Chiang Kai-shek, with assistance from the United States, attempted to orchestrate a war of resistance against Japan. In 1940, however, Japan entered into an alliance with the national government organized by Wang Jin-wei, who at times had been Chiang's ally but was now his rival. The day after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor and declared war on the United States, ROC joined America's declaration of war against Japan. Wang's nationalist government declared war on the United States in 1943, the year Japan celebrated the creation of the united front of Asiatic states . Neither Japan nor Wang's nationalist Want Jin-wei's nationalist government formerly declared war against the United States. Chiang fled Japan's forces while moving his nationalist government from Nanking (Nanjing) to Chungking (Chongqing), which Chiang considered the wartime captial of ROC. Chiang's government-in-exile attempted to orchestrate a war of resistance against Japan, but his efforts contributed little if anything to the ultimate defeat of Japan in the Pacific War. More importantly, Chiang's government had essentially lost control and jurisdiciton in most of China. By the time the war was over, Chiang's communist rivals had gained put themselves in a position to take advantage of Japan's surrender in the northern parts of China nearest Manchoukuo, and communist forces benefited from the support of Japanese stragglers who helped train and even fight alongside communist units that turned turned their attention back to their prewar revolution to overthrow Chiang's nationalist government. After Japan's surrender to the Allied Powers in 1945, Chiang's government returned to Nanking and ROC received Japan's surrender in the eastern parts of China that Japan had occupied, and in Taiwan, which the Allied Powers had agreed would be returned to China. But by 1949, communist forces had pushed Chiang's ROC government into exile on Taiwan and established the People's Republic of China in Peiping, RESUME +renamed Pei-ching (Beiping, renamed the Cairo Declaration, embedded in the Potsdam Declaration, had earmarked for return to China.slated to be returned to China.was part of Japan, , and there which remained under the collaborative 1940 gov. Chung King. a nationalist Chinese government that formed to replace the nationalist government that was in exhile JapanThey were reunited in 1955, a decade after the demise Manchoukuo in 1945 and Puyi's arrest by Chinese communists, but divorced in 1955, and he married his 5th and last wife in 1967.

The 1937 Manchoukuo Imperial Succession Law was never applied, obviously because the empire ceased to exist after 1945 -- but less obviosuly because he produced no children with any of his wives.

|

Empire of Manchou 1937 Imperial Succession Law Order of succession to Imperial Throne of the Empire of Manchou by male descendants in the male line of the Emperor Kangte |

||

Japanese textThe following Japanese text began as a copy-and-paste from a Wikisource copy attributed to the following work. 『政府公報』號外及び『滿洲國法令輯覧』 The text is that of the law at the time it was promulgated on 1 March 1937. The text is shown as received in its original form, without punctuation marks. English translationThe received English translation is my transcription from the following source. Sixth Report on Progress in Manchuria to 1939 The source describes the English version as an "Unofficial Translation". Such disclaimers are common, even on English versions of laws provided by government offices responsible for overseeing the law, because -- in principle -- only versions of the law as promulgated, in official languagaes, are recognized by courts of law. However, the Japanese version of the Manchoukuo law is an official version, because the "national languages" (国語) of Manchoukuo included Japanese.

The partial structural translations and comments are mine. |

||

| 帝位繼承法 | Position-of-the-Emperor (Imperial) succession law |

Law Governing Succession to the Imperial Throne Promulgated March 1, 1937 |

| Japanese | Structural | Received |

| 第一條 滿洲帝國帝位ハ康徳皇帝ノ男系子孫タル男子永世之ヲ繼承ス | Article 1 Regarding the position of the Emperor of the Manchou Empire, eternal generations of sons, who are male-line descendants of Emperor Kangte (康徳 SJ Kōtoku, PY Kangde), are to succeed it. | Article I The Imperial Throne of the Empire of Manchou shall be succeeded to by male descendants in the male line of the Emperor Kangte for ages eternal. | 第二條 帝位ハ帝長子ニ傳フ | Article 2 Regarding the position of Emperor, [it] shall convey (go, pass) to the Emperor's (imperial) eldest son. | Article II The Imperial Throne shall be succeeded to by the Imperial eldest son. | 第三條 帝長子在ラザルトキハ帝長孫ニ傳フ帝長子及其ノ子孫皆在ラザルトキハ帝次子及其ノ子孫ニ傳フ以下皆之ニ例ス | As for when there is no imperial eldest son, [the position of Emperor] shall convey to the eldest imperial grandson. As for when there is no eldest imperial son or any male descendants thereof, [it] shall convey to the next imperial son or descendants thereof. All [cases] subsequent to [these cases] are take (follow) these [cases] as examples. | Article 3Article III When there is no Imperial eldest son, the Imperial Throne shall be succeeded to by the Imperial eldest grandson. When there is neither Imperial eldest son nor any male descendant of his, it shall be succeeded to by the Imperial son next in age and by his descendants, and so on in every successive case. | 第四條 帝子孫ノ帝位ヲ繼承スルハ嫡出ヲ先ニス帝庶子孫ノ帝位ヲ繼承スルハ帝嫡子孫皆在ラザルトキニ限ル | Article 4 Regarding the succeeding of an imperial descendant to the position of Emperor, the [Emperor's] wife's sons are to be put first (come first, given priority). The succeeding of a concubine's son to the position of the Emperor is to be limited to when there are no imperial wife descendants. | Article IX For succession to the Imperial Throne by an Imperial descendant, the one of full blood shall have precedence over descendants of half blood. The succession to the Imperial Throne by the latter shall be limited to those cases only, when there is no Imperial descendant of full blood. | 第五條 帝子孫皆在ラザルトキハ帝兄弟及其ノ子孫ニ傳フ | Article 5 | Article V When there is no Imperial descendant, the Imperial Throne shall be succeeded to by an Imperial brother and by his descendants. | 第六條 帝兄弟及其ノ子孫皆在ラザルトキハ帝伯叔父及其ノ子孫ニ傳フ | Article 6 | Article VI When there is no such Imperial brother nor descendant of his, the Imperial Throne shall be succeeded to by an Imperial uncle and by his descendants. | 第七條 帝伯叔父及其ノ子孫皆在ラザルトキハ最近親ノ者及其ノ子孫ニ傳フ | Article 7 | Article VII When there is neither such Imperial uncle nor descendant of his, the Imperial Throne shall be succeeded to by next nearest member among the rest of the Imperial Family and by his descendants. | 第八條 帝兄弟以上ハ同等内ニ於テ嫡ヲ先ニシ庶ヲ後ニシ長ヲ先ニシ幼ヲ後ニス | Article 8 | Article VIII Among the Imperial brothers and the remoter Imperial relations, precedence shall be given, in the same degree, to the descendants of full blood over those of half blood, and to the elder over the younger. | 第九條 帝嗣精神若ハ身體ノ不治ノ重患アリ又ハ重大ノ事故アルトキハ参議府ニ諮詢シ前數條ニ依リ繼承ノ順序ヲ換フルコトヲ得 | Article 9 | Article IX When the Imperial heir is suffering from an incurable disease of mind or body, or when any other weighty cause exists, the order of succession may be changed in accordance with the foregoing provisions with the advice of the Privy Council. | 第十條 帝位繼承ノ順位ハ總テ實系ニ依ル | Article 10 | Article X The order of succession to the Imperial Throne shall in every case relate to absolute lineage. | 附則 本法ハ公布ノ日ヨリ之ヲ施行ス | Article 1 As for this law enforce it from the day of promulgation. | Supplementary The present Law shall come into force on the day of promulgation. |