Words do matter

When criticism distorts the truth

By William Wetherall

First posted 15 August 2025

Last updated 5 January 2026

Densho's critical lexicography

Roger Daniels' "Words Do Matter" (2005)

•

Densho's discussion of "Words Do Matter" (2009)

•

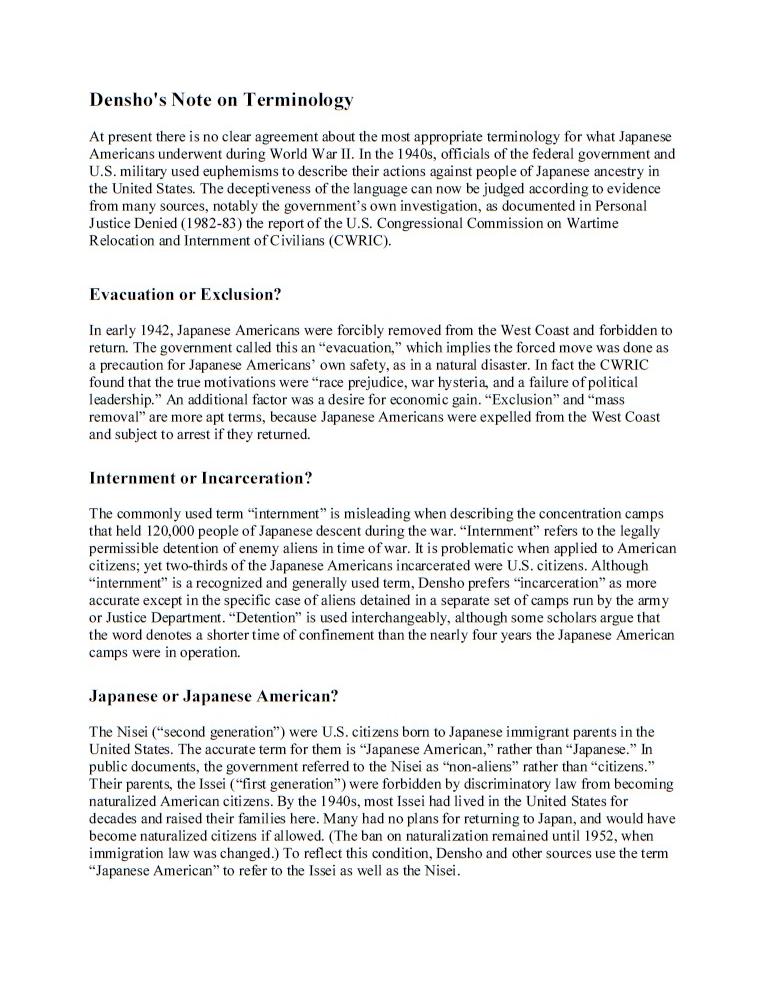

Densho's note on terminology (2016)

False metaphors vs. officialese

Forced Removal vs. Evacuation

•

Incarceration vs. Internment

•

Japanese Americans vs. Japanese

•

Concentration Camps vs. Relocation Centers

Related articles

The Heymans and Yasuis of Grass Valley and Hood River: Different roots, common struggles, shared dreams

Henry Mittwer (1918-2012): Finding himself in a story not of his making

DeWitt's Final Report, 1942: The mixed standards of exemption from internment

The banality of evil: The relocation of Japanese Americans

Densho's critical lexicographyOver 80 years have passed since the exclusion of "all persons of Japanese ancestry" from their west coast homes in military exclusion zones, to inland relocation camps from which they could be resettled in communities east of the exclusion zones. The experiences of the 110,000 to 125,000 or so "persons of Japanese ancestry" who were subjected to government exclusion orders -- American citizens racialized as Japanese, and Japanese subjects and nationals among other aliens racialized as Japanese -- have been the topic of hundreds of books and thousands of articles. In recent years, more writers, when describing the exclusion, have chosen to replace contemporary officialese with terminology recommended by "critical" scholars, who regard the contemporary officialese as "euphemisms" intended to put a deceptive gloss on the racist injustices that the U.S. government committed in the name of national security. Criticism of the exclusion as something other than "evacuation" and "relocation" goes back to the period that the government's exclusion orders were court enforced, from 1942 to 1944. But the movement to reject the officialese was given its most significant impetus by Roger Daniels (1927-2022) in his 2005 article Words Do Matter: A Note on Inappropriate Terminology and the Incarceration of the Japanese Americans (see below). Densho -- an organization engaged in "Preserving stories of the past for the generations of tomorrow" -- twirled publicized Daniels' "Words Do Matter" article and came up with its own guidelines for "appropriate" usage in lieu of the historical officialese and related usage, which Daniels and argued were deceptive when not simply incorrect. "Densho" (伝書、傳書) in Japanese are "books" or "writings" (sho 書) that convey (den 伝、傳) information -- such as esoterica, trade secrets, family history -- to successors or descendants. Densho's website is dedicated to keeping stories about the wartime exclusion alive. Yes, but . . .I take a somewhat different position. I use the official terms, not to excuse the exclusion or the manner in which it unfolded, but because -- while they smack of the banality that characterizes a lot of bureaucratese -- they come far closer to the truth than the critical metaphors -- which either gloss over ideologically inconvenient facts, or are simply false. I use the official terms, or related terms, to (1) make distinctions between the kinds of exclusion actions and their intent, and (2) dramatize the disconnects between the official terms and the actions taken in their name without reducing the descriptive terminology to badly applied ideological make-up. In fact, the official terms are not "euphemisms" but made necessary distinctions. The "wartime relocation centers" or "internment camps" -- never mind their barbed wire fences and guard towers -- were not "prisons" or "jails". Internees were not "incarcerated" or "imprisoned" in the camps, but held there until they could be cleared for release to locations outside the areas from which they had been excluded. While the assembly and relocation centers could be called "concentration camps" in the broadest sense of this term -- as a place where people are brought together and detained for whatever reason, most likely against their will and without due process -- "concentration" focuses on the condition or state of having been removed and confined -- not the intent or purpose. Whereas "evacuation", "assembly", and "relocation" clearly allude to the before, during, and after. The exclusion orders should never have been issued, and contemporary lawmakers and courts should have immediately over turned and voided them. But this only makes the evacuation and internment of "all people of Japanese ancestry" a grave injustice, not an atrocity. The assembly and relocation centers were unwarranted. If segregation was legal for enemy aliens, it was not legal for non-alien citizen descendants of enemy aliens. The racialist paranoia was expected, but using it as a pretext for exclusion was immoral if not illegal. Those subjected to the exclusion orders could not help but feel that the exclusion orders were wrongful. They could not but feel helpless against the threat of physical enforcement should they choose not to comply. And of course they had reason to compare the conditions, in fenced and patrolled facilities, from which they needed permission to leave, to those of a jail or prison. But were the camps either jails or prisons? No. Was confinement punitive? No. Historians, as critics, are not wrong to condemn the exclusion of "all persons of Japanese ancestry" from west coast military zones as gross and racist violations of constitutional rights -- need to understand WRA's policies and their implementations for what they actually were. And and they bear no resemblance to the maltreatment, violence, and genocide perpetuated in numerous concentration and POW camps in the European and Pacific theaters of World War II and other wars. I cite the undisguised racism articulated in the wartime orders issued by General DeWitt under the authority of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. But I also describe the manner in which "all persons of Japanese Ancestry" on the west coast -- practically to a person -- voluntarily and peacefully submitted to military orders in good faith, as they were herded like cattle into assembly centers, and then sent to relocation centers with guard towers and barbed wire fences patrolled by armed guards. In doing so, I use the official terms, trusting that readers will feel the enormity of the federal government's actions -- not only against long-settled law-abiding aliens who happened to qualify as enemy aliens the day after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor -- but also against American citizens who happened to be of enemy-alien descent, whose loyalties should never have been doubted, and who as citizens should never have been denied their freedom without due process of law on an individual basis, to be presumed beyond suspicion of posing a threat to military security without incontrovertible evidence of having been engaged in traitorous activities. I am a believer in dramatizing -- showing, not telling -- stories. Good history, like good fiction, is portraying realities in such a way that readers participate in the story, rather than narrate the story using "critical" terms intended to lead to reader to conclusions not supported by the facts. I trust that readers -- presented with the facts, all the facts, and nothing but the facts -- are capable of coming to their own conclusions, without being told how to think. The banal officialese actually underscores the government's disregard for the rights of American citizens, if not also the rights of law-abiding legal aliens, racialized as "Japanese" and thought for that reason alone to constitute a threat to national security following Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor. "Evacuation" suggests there were indisputable grounds for evacuation -- but there were none. "Relocation" suggests that there were indisputable grounds for resettling evacuees elsewhere -- but there were none. The exclusion orders mandated evacuation as the first step toward relocation. Relocation meant resettlement outside the exclusion zones. Relocation Centers were facilities for staging resettlement. Those for whom evacuation orders were directed were thus compelled to follow the orders or face legal consequences. However, it is historically inaccurate to describe the evacuation as "forced removal" -- without pointing out that all but a few people peacefully complied with the orders, both in keeping with their personal law-abiding characters, and in consequence of consensuses within their communities, nurtured by community leaders, who saw compliance as the best way to demonstrate loyalty to the United States. As make-shift, primitive, and uncomfortable as the facilities used to first assemble evacuees and then move them to relocation centers may have been -- and as reasonable as it may seem for evacuees and relocatees to feel as though they had been incarcerated for the crime of being of "Japanese ancestry" -- there is simply no foundation in evidence-based historiography for regarding the facilities as "prisons". In summary -- I like history raw and real, not filtered through ideology. The "euphemisms" were what they were -- reasonably accurate names for what the exclusion orders sought to accomplish. In good history as in good fiction, the pains and sorrows of life, the poignancies and ironies of the human condition, the injustices -- and, yes, the atrocities, if that be the case -- speak for themselves. Daniel Rogers (2005)The views of "inappropriate terminology" espoused by the late Daniel Rogers (1927-2022), one of the most prolific scholars and writers on Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans, continue to influence many writers. Daniels argued that "incarceration" best describes the actions taken against Japanese Americans and Japanese sent to so-called "relocation centers" also known as "internment camps" -- while "internment" properly describes only the dispositions of aliens held after arrests, detainments, and hearings conducted in accordance with established law and procedures. Apart from whether the apprehensions and detainments of Japanese were justified, Japanese were aliens. They were subjects and nationals of Japan. Japan had militarily attacked the United States at Pearl Harbor and declared war on 7 December in the United States. The following day, the United States reciprocated Japan's declaration of war, and legally declared Japanese in the United States as enemy aliens. Suspicious individuals had already been subjected to surveillance by the FBI. Now they could be detained and interrogated, and their homes subjected to search and seizure investigations. And enemy aliens who were felt to constitute security risks could be apprehended and detained for as long as the war continued. Whether apprehensions of enemy aliens was justified, or whether the hearings and the dispositions based on the hearings were fair, is another question. Daniels' point was that the U.S. government was aware that, when taking what were essentially political actions in time of war against declared enemy aliens -- subjects, nationals, or citizens of a country with which the United States was at war -- the actions were subject to scrutiny in the eyes of international law, including applicable conventions and treaties. And the United States had laws and procedures for such actions. Not so, he says, in the case of Japanese Americans -- meaning U.S. citizens of putative Japanese ancestry (Daniels 2005, Part 2, my [bracketed (remarks)]. Thus [Japanese (and other) enemy alien] internees had a very different kind of existence from that of most Japanese Americans. While the decision to intern an individual may not have been just, internment in the United States generally followed the rules set down in American and international law. What happened to those West Coast Japanese Americans who were incarcerated in army and WRA concentration camps was simply lawless. Lawless?"Lawless" has two meanings. The most general meaning describes a situation in which something happens in a haphazard, unregulated, perhaps whimsical, arbitrary, or random manner -- i.e., without the benefit of laws or principles of action or behavior. More narrowly, it refers to a lack of civic order. Daniels was wrong on both counts. What happened to "all persons of Japanese ancestry" was "lawless" in neither sense of the word. Every measure taken to "exclude" them from designated military zones was effected by laws and regulations authorized by executive orders. Several contemporary Supreme Court rulings, which split on some arguments, accepted in their majority that the exclusions were within the powers of government in time of war. By "lawless" Daniel seems to mean "illegal" -- for he contends that everything done in the name of Executive Order 9066 was unconstitutional, and otherwise violated basic human rights. This is a personal opinion, with which I would generally agree -- with some reservations. The unconstitutionality of Executive Order 9066 is debatable. The legality of what ensured some from the order -- how officials empowered with carrying it out both interpreted it and applied it in the execution of their duties -- is also debatable, but much less defendable on legal grounds, and undefendable on moral grounds. Still, it would be wrong to think of the exclusion -- the evacuation and relocation -- of 110,000, 120,000, 125,000) or so Americans and Japanese who were herded into quickly constructed army-like camps in areas remote from their homes -- as "lawless". Given the speed with which the exclusions were carried out, and the number of people removed, there was some confusion. But on the whole, the exclusion was highly organized and orderly. The exclusion unfolded in pretty much clockwork fashion, in concert with the mechanisms set in place by military and civilian planners. In other words, the exclusion was the epitome of "lawful" and "orderly" procedure -- beginning with several executive orders, and the numerous legal and bureaucratic measures and guidelines that followed. Right or wrong, Executive Order 9066 and related executive orders -- and the litany of other measures that were established under their authority, or in their spirit, by congress, the bureaucracy, and the military -- were "laws". Expedient, yes. Made on the fly -- partly to deal with rapidly changing wartime conditions, and partly to exploit incidental, racially motivated opportunities -- yes. But nonetheless, the exclusion was the product of litigious and bureaucratic civilian and military minds. Elected or appointed government officials -- politicians, bureaucrats, military officers -- can do very little without the "authority" of a law or regulation. All learn how to exploit the flaws of laws and regulations, and circumvent them to achieve institutional or personal goals. But herding 110,000 "persons of Japanese ancestry" into barbed-wire corals in the middle of nowhere is not something the United States government could have done "lawlessly". It is one thing to allege -- and prove -- that individuals like General DeWitt took advantage of his authority, to aid and abet the political and economic interests of the white bigots on the west coast, who for decades had dreamed of ridding the west coast of its Oriental vermin, beginning with Chinese, and now Japanese. It is quite another thing to allege that DeWitt and his accomplices did so lawlessly. If there were rewards for how to mobilize people and resources to set up 15 assembly centers, and build 20 more permanent relocation centers -- then to orchestrate the logistics needed to feed, educate, entertain, and in many other ways sustain the lives and maintain the mental health of 110,000 souls behind barbed-wire -- the Department of War, and the Wartime Civil Control Administration and and War Relocation Authority, deserve a number of medals. Also deserving medals are the "law abiding" adults among the 110,000 souls who voluntarily submitted to the orders to evacuate their homes. Like them or not -- and whether or not they were warranted or just or even constitutional -- the orders were seen as expressions of the will of the United States government. The government was insisting that "all persons of Japanese ancestry" cooperate. So, too, were the leaders of the Japanese American Citizens League -- the mission of which was to protect Japanese American citizens. Should "all persons of Japanese ancestry" have submitted to evacuation and relocation so peacefully? Could they not have simply refused to go? What if -- instead of urging compliance -- JACL had supported Hirabayashi, Yasui, and others who felt the way they did, orchestrated community support where possible, and organized peaceful protests? There seems to have been no shortage of individuals who were not of "persons of Japanese ancestry" -- though their percentage of the total population may have been extremely small -- who were willing to articulate the rights of Americans of Japanese ancestry as U.S. citizens. There were also people willing, ready, and able to advocate on behalf of the issei immigrants who had become enemy aliens. Would "persons of Japanese ancestry" who simply refused to abandon their homes and businesses -- and peacefully insisted on their personal freedom in the absence of evidence that they had engaged in espionage or otherwise posed a threat to military security -- have been subjected to violent invasions of their homes by military forces or police, or been massacred by vigilantes? That fact is, laws were used -- undoubtedly abused, but none the less used -- for the purpose of excluding "all persons of Japanese ancestry" from the west coast war zones. The removal program -- the evacuations and relocations -- were in accordance with lawfully established orders and procedures. Racist? Absolutely. Unjust? Absolutely. Unconstitutional? Arguably yes, at least in the case of American citizens. But "lawless"? No. Densho's discussion of "Words Do Matter" (2009)Densho ran Roger Daniels' 2005 article "Words Do Matter: A Note on Inappropriate Terminology and the Incarceration of the Japanese Americans" in five parts on its website in early February 2008.

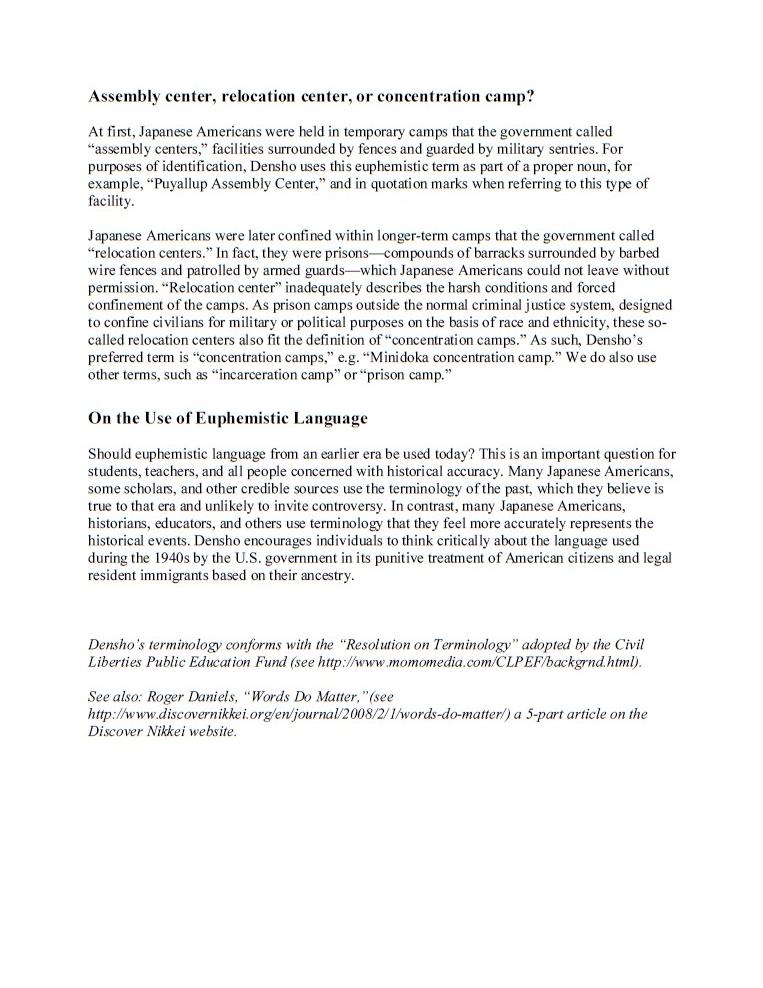

1 February 2008 Part 1 of 5 The following year, Densho invited visitors to discuss Daniels' article as a step toward developing a terminology guide (see image to right). Densho's note on terminology (2016)By 2016, Densho was publicizing terminogy recommendations, reflecting its "critical" understanding of the evacution and relocation experiences of "all persons of Japanese ancestry" during the Paficic War (see image to right). Over the years, Densho has refined its terminology recommendations and shared them on social media. Densho's content includes personal testimony and opinion, and jounalistic and academic topical reports that vary in quality from very high to rather low. Not all content contributors follow Densho's terminology recommendations, but many do. Elsewhere, Densho's guide to Japanese American WWII Incarceration Terminology (below) on "euphemisms" -- and other officialese it regards as deceptive or wrong -- has influenced, and distorted, the ways many writers have chosen to characterize the U.S. government's wartime removals of "all persons of Japanese ancestry" from the west coast exclusion zones to inland relocation camps. |

||||||||||||||||

False metaphors vs. officialeseDensho has posted different versions of its terminology guide on social media. It has, for instance, an Instagram page called denshoproject, which publicizes various Densho projects, including a Japanese American WWII Incarceration Terminology guide it shares with publichistorians, the Instagram page of the National Council on Public History (NCPH), which has the following mission (as of 15 August 2025). NCPH inspires public engagement with the past and serves the needs of practitioners in putting history to work in the world by building community among historians, expanding professional skills and tools, fostering critical reflection on historical practice, and publicly advocating for history and historians. The keyword here is "critical reflection". And the terminology issues Densho raises regarding the history of the Pacific War removal of "all persons of Japanese ancestry" from designated west coast military exclusion zones, are raised from the standpoint of "critical scholarship" -- which focuses on issues like power, inequality, social justice, and a litany of related topics, in the interest of challenging and reconstructing conventional wisdom and the status quo. The main problem with "critical scholarship" is that it tends to put theory, which is likely to reflect a political ideology, before careful discovery and analysis of facts. Critical scholars seek to revise history in accordance with their preconceived notions "truth". For sure, all histories press one or another view of the human condition into the service of a world view. An no history is immune from revision. The only question in scientific historiography is whether a revision improves the truthfulness of history by introducing new facts or more credible versions old facts, or higher quality analysis. Critical historians rewrite received histories -- which full of biases, euphemisms, and silences -- to reflect, they argue, other voices, which they believe tell truer stories about the past. If done with respect for facts, critical histories can definitely be truer. But if inconvenient facts are ignored, or subverted by ideology, the results are analogous to painting a lidded garbage can with flowers and believing it is a flower garden. Some efforts to write the "euphemisms" out of the received official accounts of the evacuations, relocations, and other dispositions of "all persons of Japanese ancestry, both alien and non-alien" during the Pacific War, amount to subordinating history to ideology rather than facts. "words can lie or clarify"Densho Project (Instagram), in collaboration with Public Historians (Instagram, National Council on Public History"), offers this pretext for revising terminology (retrieved 15 August 2025). In the words of Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga, a camp survivor who would go on to play a pivotal role in obtaining redress for Japanese Americans, "words can lie or clarify." When we use language that distorts the past, we lose our ability to recognize patterns of repeating history. But language that imparts truth and understanding can help us avoid repeating those same mistakes today. The problem is when the "clarifications" themselves mask and muddy the underlying truths that, because they are redressed in ideologically comfortable clothing, cannot be understood in a way that is likely to realize the dream of not repeating the past. The allegation that words like "evacuation" and "relocation" are somehow "lies" -- and that "forced removal" and "incarceration" are truthful clarifications -- is extremely problematic. It assumes that the government officials who used "evacuation" and "relocation" were "lying" or otherwise intended to mislead the public as to the intentions of the removals of "all persons of Japanese ancestry" from the west coast exclusion zones. But in fact, "evacuation" and "relocation" are arguably the best and most truthful terms possible. "Forced removal" fails to properly characterize the evacuation -- which would have been impossible without the peaceful cooperation of the evacuees. "Incarceration" totally obscures the purpose of the removal -- to relocate evacuees elsewhere in the United States. |

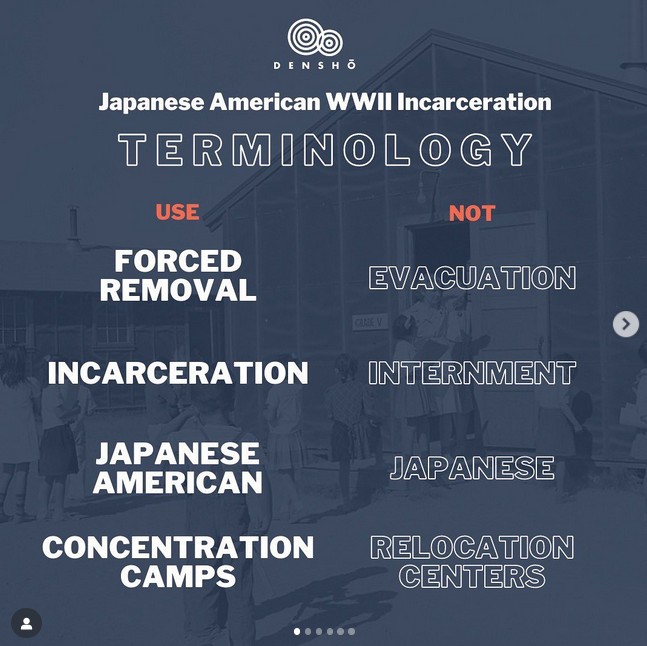

"Forced Removal" vs. "Evacuation"Densho's concerns about "Evacuation", as of 30 December 2025, were as follows. Forced Removal vs. Evacuation In early 1942, Japanese Americans were forcibly removed from the West Coast and forbidden to return. The government called this an "evacuation," implying the forced move was a precaution for Japanese Americans' own safety, as in a natural disaster. In reality, this was a targeted exile of a single ethnic minority -- carried out by armed soldiers, enforced by lawmakers and elected officials, and motivated, in part, by a desire to reap economic gains from the farmland and property Japanese Americans were forced to leave behind. "Exclusion" and "mass removal" are therefore more apt than euphemisms such as "evacuation" and "relocation," because Japanese Americans were expelled from the West Coast and subject to arrest if they returned. The Western Defense Command and Fourth Army Wartime Civil Control Administration bills -- which notified "all persons of Japanese ancestry, both alien and non-alien" that they "will be evacuated from" the area on a designated date, cited the "exclusion order" that authorized the evacuation of the area. The orders were both racialist and racist to their conceptual core. They were clearly motivated by fear if not hatred of "the Japanese race". And some exclusionists were undoubtedly anticipating the elimination of "the Japanese" from agricultural communities in all in all west coastal states. Never mind the state of war between the United States and Japan, and the legality of Roosevelt's Congress should have tolerated the orders. They should never have been issued. Nor should they have been condoned by any individual or organization that understood nationality laws and due process under the United States Constitution at the time -- including the Japanese American Citizens League. JACL, however, panicked. Instead of martialling support for peaceful persuasion of government authorities to adopt policies that protected individuals from arbitrary exclusion without due process, JACL decided to go along with the Army's scheme. There were plenty of people who felt exactly like Gordon Hirabayashi and Minoru Yasui, and the attorneys that assisted them and others who supported their causes. But most people lacked the courage when it came to putting themselves on the line without wider community support. How many would have peacefully simply declined to observe the curfew and evacuation orders -- had JACL and other community leaders adopted the position of organized civil disobedience? As things turned out, most "persons of Japanese ancestry" voluntarily complied with the orders, resulting in their "mass removal" -- for which General DeWitt, in Final Report: Japanese Evacuation From the West Coast, 1942, thanked "the Japanese" -- and Secretary of War, Henry L. Stimpson, War Department Secretary Henry Stimpson added this. To the Japanese themselves great credit is due for the manner in which they, under Army supervision and direction, responded to and complied with the orders of exclusion. The banality of evil doesn't get better than this. But historical truth requires that today's descendants of "the Japanese" clearly understand the degree that their ancestors accepted JACL's leadership, which like a bellwether, beckoned them to follow the herd to the temporary holding pens (assembly centers) -- then to the more permanent holding pens (relocation centers), from which, if they were good sheep, would be allowed to roam free anywhere outside the evacuated areas. Densho's "a single ethnic minority" characterization is not true. The phrase "all persons of Japanese ancestry" is a racial reduction of an ethnically complex cohort to "a single race" -- the putative members of which were treated the same regardless of whether they were "alien or non-alien" by nationality. Nominally "cultural" (ethnic) distinctions were, in fact, made, as in cases of "persons of Japanese ancestry" who were acknowledged as being of half or less "Japanese blood". |

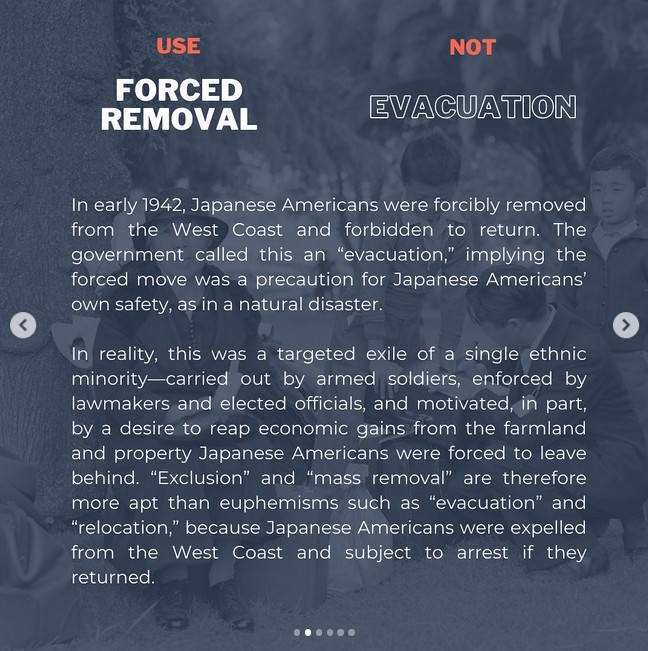

"Incarceration" vs. "Internment"Densho's concerns about "Internment", as of 30 December 2025, were as follows. Incarceration vs. Internment The commonly used term "internment" fails to accurately describe what happened to Japanese Americans during WWII. "Internment" refers to the legally permissible, though morally questionable, detention of "enemy aliens" in time of war. There were approximately 8,000 Issei ("first generation") arrested as enemy aliens and subjected to what could be described as "internment" in a separate set of camps run by the Army or Department of Justice.[*] This term becomes a misleading, othering euphemism when applied to American citizens detained by their own government; yet two-thirds of Japanese Americans incarcerated during WWII were U.S. citizens by birth and right. Although "internment" is a recognized and widely used term, we encourage the use of "incarceration," except in the specific case of Japanese Americans detained by the Army or DOJ. "Detention" is used interchangeably -- although some argue that the word denotes a shorter period of confinement than the nearly four years the camps were in operation. [*] A smaller number of Nisei, mostly Kibei and mostly in Hawai'i, were also swept up in the DOJ internment system. "Incarceration" metaphorically resonates with Densho's position that the internment camps were "prisons" and that internees were detained in the camps for punitive purposes. But the camps were definitely not "prisons" in concept or actuality. And even the "enemy aliens" and the few nisei who were held in the Department of Justice camps were not interned for punitive purposes. They were under fairly conventional laws that provided for the isolation of persons designated as "enemy aliens" during time of war. Kibei were often regarded as similar to issei in that they had resided in and been schooled in Japan and were suspected of being dual nationals. Japan's treatment of Americans, British, and other Allied nationals in Japan was not unlike America's treatment of Japanese subjects and nationals in the United States -- though Japan had a greater variety of facilities, and the facilities were much smaller, on account of the fewer numbers of enemy aliens in Japan. See Alien and native enemies: Nationality and blood in time of war in the article on Henry Mittwer (1918-2012): Finding himself in a story not of his making in the "Nationality" section of Yosha Bunko. The important take away from the nature of enemy alien camps in both Japan and United States is that they were generally operated within internationally recognized conventions for the treatment of enemy aliens in times of war. They were not prisons as such. And their detainees were not regarded as "prisoners of war". That during the years America was at war with Japan, Germany, and Italy, its enemy alien camps were more likely to detain Japanese than Germans or Italians, might be seen as a reflection of America's greater racial fear of Japanese. But part of the differential treatment of Japanese versus Germans and Italians is attributable to the fact that neither Germany nor Italy initiated a war with the United States by attacking its territory. |

"Japanese Americans" vs. "Japanese"Densho's concerns about "Japanese"", as of 30 December 2025, were as follows. Japanese American vs. Japanese Media outlets and other sources often refer to the more than 120,000 [*] people of Japanese descent imprisoned by the U.S. government during WWII as simply "Japanese" -- but this both erases their American identity and conflates Japanese Americans with Japanese citizens in Japan. The wartime government employed this strategy itself, inventing the orwellian term "non-alien" to describe Japanese American citizens in public documents. The Nisei ("second generation") were U.S. citizens born to Japanese immigrant parents in the United States. Many had never set foot in Japan. Their Issei parents were forbidden by discriminatory law from becoming naturalized American citizens, but by the 1940s most had lived in the United States for decades and raised their families here. Most had no plans of returning to Japan, and would have become naturalized citizens if allowed. By birth or by choice, Japanese Americans were just that -- American. [*] The oft-cited "120,000" figure comes from the War Relocation Authority's official statistical compilation, The Evacuated People, which cites a total of 120,313 people in the WRA system. However, including DOJ/Army internees and those who were held in "assembly centers" but resettled before being transferred to WRA custody, that number is closer to 126,000. The characterization of "Japanese Americans" in this statement is full of errors or commission and omission. The most egregious error is the conflation of "Japanese", which properly should at the time have referred only subjects and nationals of Japan -- with Americans of putatively Japanese descent. Even if allowable to call the latter "Japanese Americans", the former were not "Americans". That was the historical reality -- like it or not. The regard of Japanese in the United States at the time as "Japanese Americans" reminds of John Lie's attempt to exempt Koreans born in Japan as aliens, from their alien status, by regarding them as "Korean Japanese" on the grounds that they grew up speaking Japanese, and are generally socially and culturally indistinghishable from most Japanese. Whether someone born in Japan to one or two Korean parents becomes Korean, or Japanese, or another nationality, is an artifact of applicable nationality laws. Lie reasons that people born as Korean aliens in Japan would have been born Korean Japanese were Japan to have place-of-birth law like the United States. Anyone born in Japan with a drop of Korean blood as "Korean Japanese" -- regardless of their nationality -- creates a legal falsehood. Densho's lumping Japanese together with Japanese Americans is similarly an untruthful fabrication. Some writers refer to "more than 120,000 people of Japanese descent". The term "Japanese descent" is synonymous with "Japanese ancestry" as used in the wartime phrase "all persons of Japanese ancestry" -- a purely racialist description having nothing to do with nationality in its legal sense of civil status as an affiliate of a state. There can be no conflation of "Japanese Americans" with "Japanese citizens" in Japan except through racialization as "persons of Japanese ancestry". In point of fact, there were no "Japanese citizens" at the time of the Pacific War but only "Japanese subjects and nationals". Japan's domestic laws to do not define "citizens" or "citizenship", but only nationality. And nationality is only one factor in the rights and duties of nationals and aliens in Japan. About 1/3rd of the racialized "Japanese" that were detained in various ways during the Pacific War in the United States were "subjects and nationals" of Japan. That is why they were "enemy aliens" -- whereas the other 2/3rds were "non-aliens" -- i.e., Americans who happened to be of racialized Japanese ancestry. So "Japanese" in the expression "all persons of Japanese ancestry [descent]" conflated all aliens in the United States of putatively "Japanese ancestry" with all "non-aliens" in the United States who were racialized as "Japanese". "Non-alien Japanese" referred of course to citizens or nationals of the United States who were racialized as "Japanese". "non-aliens"Was "non-aliens" really Orwellian? Let's examine the facts.

Some critics have suggested that the exclusion orders spoke of "non-alien" to avoid the term "citizen". But Dewitt's Final Report clearly recognizes that "American citizens of Japanese ancestry" are included along with "alien Japanese". Note that "alien Japanese" is not limited to aliens of Japanese nationality, but aliens of any nationality who are of racialized "Japanese ancestry". The "alien and non-alien" dichotomy is about nationality. Not that the term "non-alien" includes not only "U.S. citizen" or "American citizen", but also "U.S. (American) national" -- a non-alien non-citizen, who possesses U.S. nationality but not U.S. citizenship. Racially barred from naturalizationWhile true that contemporary U.S. laws generally forbade Japanese immigrants from naturalizing on account of the putative "Oriental" race, this does not qualify them as "Americans" in the sense that their offspring, born in the United States, were "Americans". Some -- perhaps even most -- might have naturalized, had they been permitted to. But that was not the reality. The reality was that they couldn't. This cold historical fact dictates that, at the time of wartime internments, Japanese immigrants -- no matter how long they had been in the United States, and no matter how many aspired to be U.S. citizens -- were aliens, and not Americans. This truth is totally distorted by conflating Japanese" and "Americans" under the romantic heading "Japanese Americans". I say "romantic" because conflating "Japanese" and "Americans"-- erasing the alien/non-alien distinction -- serves the purpose of achieving birds-of-feather "solidarity". Bringing wartime "Japanese" issei into "Japanese American" nisei and sansei fold establishes a "community" with a common blood-conscious ancestry. The "Japanese American" conflationists could paraphrase DeWitt's definition of "Japanese", to wit -- A "Japanese American" is "Any person [in the United States] who has a Japanese ancestor regardless of degree [of Japanese blood]". Conflating "Japanese" aliens with "Japanese American" non-aliens is also romantic in the sense that it is tantamount to painting a lidded garbage can with flowers and imagining it is flower garden. Some writers about "Koreans in Japan" have declared they are really "Japanese" because they were born and raised in Japan, and should by rights be Japanese -- if only Japan had a right-of-soil nationality law like the United States, or even a second-generation nationality provision like some right-of-blood states in Europe. But the reality is that many Chosenese and Koreans in Japan, who were born and raised in the country, choose not to naturalize. Nationality is what it is, whether or not one has a choice. Whereas no no one chooses their nationality at birth. Settlers and sojournersThere were broadly two kinds of Japanese in the United States at the start of the Pacific War. Most were Japanese who had emigrated to and settled in the United States long before the war -- who before the war could fairly easily get permission to leave the U.S. to visit Japan and return to America as domiciled aliens. Other Japanese, fewer in number, had more recently come to the United States on specific activity visas, and would not so easily have gotten re-entry permits. Enemy alien status, however, was based entirely on nationality, not immigration status. Japanese became enemy aliens, whether they had just stepped off a boat the day before Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, or had lived in the United States for half a century. Some Japanese enemy aliens were apprehended and detained as enemy aliens. Most. however, were treated on a par with Americans of Japanese ancestry. They were evacuated from their residences to relocation centers, from which -- like Americans of Japanese ancestry -- they were resettled in other localities, if they were seen as posing no security risk. As Japanese, issei were subjects and nationals of Japan -- subjects of the Emperor and nationals of the state. As legal aliens in the United States, males were subject to Provost Marshal General's Office military draft registration during the Great War, later known as World War I. They were also subject to Department of Selective Service military draft registration during World War II, including later the Pacific War. At the time Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, a number of Japanese Americans were serving in the Armed Forces of the United States. And there were not a few Japanese American reservists, including officers like Minoru Yasui. Their race did not disqualify them from military service. However, for a year or so after Pearl Harbor, Americans of Japanese ancestry were not accepted as enlistees or inductees. And Minoru Yasui was not allowed to activate his reserve status. "Japanese American"The term "Japanese American" is not a legal classification in U.S. nationality law. If one is a U.S. citizen or national, then one may be called an "American" -- but is legally a "citizen" or a "national" as the case may be. The two statuses are not the same. Whatever significance "Japanese" might have, as a qualification of "American", it is strictly personal, and is irrelevant to the question of whether one is, or isn't, an American. The same is true of "Japanese" as a term for someone whose status is that of national (or at the time of the Pacific War, a subject and national) of Japan. It signifies only civil status -- not race or ethnicity. The putative race or ethnicity of a Japanese national is a private matter, and is irrelevant to the civil status of being Japanese. There is some usage of "Japanese American" to signify dual nationality -- meaning only that the person possesses two civil statuses -- one as a national of Japan, the other as a citizen or national of the United States -- regardless of one's race or ethnicity or mixture thereof. However, since neither Japan nor the United States positively recognizes dual nationality (both merely tolerate it), neither state acknowledges the term "Japanese American" as a label for someone who happens to possess the nationalities of both. There is also some usage of "Japanese American" to mean someone who is racially mixed, in the racialist sense of being "part Japanese" by blood and "part American" by blood. By and large, however, "Japanese American" is used to signify an "American" citizen (or national) who is biologically (genetically, racially) of racialized "Japanese" descent. Whatever its intended usage, "Japanese American" cannot possibly be a "substitute" for "Japanese" as this term was used by both the U.S. government and the press -- and by both Americans and Japanese for that matter -- during the Pacific War. Today, 80 years later, the essentially "racialism" in the "Japanese American" community is one that regards "being Japanese" as a matter of biology -- hence the changing and controversial "blood quantum" requisites for being a "Cherry Blossom Queen". The technical language in DeWitt's Final Report -- never mind the false claims in the report's War Department justifications for evacuation and relocation -- is historically truthful, whereas Densho's desire to paint 110,000, 120,000, or 125,000 or so Americans and Japanese as "Japanese Americans" is historically deceptive. Nationality was important -- as roughly 5,000 Americans who renounced their citizenship, and found themselves treated as Japanese, discovered. Had conservatives in the Department of Justice had their way, all the renunciants would have been deported to Japan. Some were, before deportation orders were stayed and, eventually, most renunciations were voided. See Henry Mittwer (1918-2012): Finding himself in a story not of his making for stories about American citizens who, under duress, became enemy aliens. In conclusion"All persons of Japanese ancestry" -- and its common reduction to "Japanese" -- are history, red in racialist tooth and claw. They are the realities that matter. "Japanese and Americans of Japanese ancestry" -- as a recasting of the above in more civil terms -- is also historically accurate. There were "Japanese" subjects and nationals, who were aliens, and U.S.-born descendants who were American citizens, hence non-aliens. "Japanese Americans" is a plausible way of phrasing "Americans of Japanese ancestry". But conflating "Japanese" into "Japanese Americans" is falsification of facts. Aliens are aliens. Citizens are citizens. Legally, aliens and citizens may be treated differently in some instances, and similarly or the same in others. But their essential statuses are different. Socially, Japanese and Japanese Americans are commonly racialized. And "Japanese Americans" are commonly conflated with "Japanese" -- exactly as they were during the Pacific War. How many times have I heard a "Japanese American" speak of "Japanese" as a race? Identify with nationals of Japan as racial siblings? Quantify Japanese blood as pure, half, quarter, or whatever? Densho is right to object to the use of "Japanese" as a racialist conflation of "Japanese Americans" and "Japanese". But this does not justify the equally racialist conflation of "Japanese" with "Japanese Americans". Such conflation is at best ahistorical, at worst delusional. |

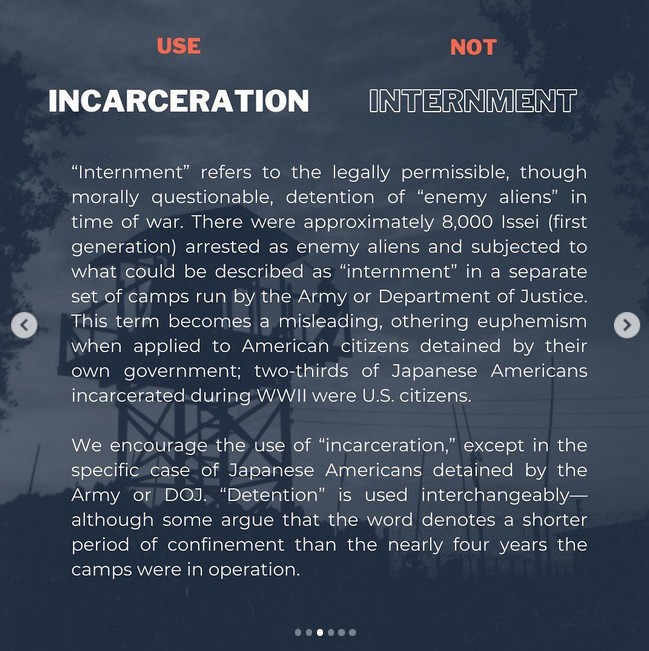

"Concentration Camps" vs. "Relocation Centers"Densho's concerns about "Reclocation Centers", as of 30 December 2025, were as follows. Concentration Camps vs. Relocation Centers There is still some debate over the most appropriate terminology for the camps where Japanese Americans were confined during WWII. At first, Japanese Americans were held in temporary camps the government called "assembly centers" -- facilities surrounded by fences and guarded by military police. This term is clearly euphemistic in nature, as the "assembly" was carried out by military and political force. Therefore, we recommend its use only as part of a proper noun (e.g. "Puyallup Assembly Center") or in quotation marks for specific references to this type of facility. Japanese Americans were later transferred to longer-term camps which the government called "relocation centers." (Some officials, including the president, also referred to them as "concentration camps" in internal memos.) Despite the seemingly innocuous name, these were prisons -- compounds of barracks surrounded by barbed wire fences and patrolled by armed guards -- which Japanese Americans could not leave without permission. "Relocation center" fails to convey the harsh conditions and forced confinement of these facilities. As prison camps outside the normal criminal justice system, designed to confine civilians for military and political purposes on the basis of race and ethnicity, these sites also fit the definition of "concentration camps." As such, Densho's preferred term is "concentration camp" (e.g. "Minidoka concentration camp"). We do also use other terms, such as "incarceration camp" or "prison camp," but urge the avoidance of euphemisms such as "relocation center" and "internment camp." Our use of "concentration camp" is intended to accurately describe what Japanese Americans were subjected to during WWII, and is not meant to undermine the experiences of Holocaust survivors or to conflate these two histories in any way. Like many Holocaust studies scholars, we believe that "concentration camp" is a euphemism for the Nazi death camps where millions of innocent Jews and other political prisoners were killed. America's concentration camps were very different from Nazi Germany's, but they, and dozens more historical and contemporary examples, do have one thing in common: "people in power removed a minority group from the general population and the rest of society let it happen." Not only did the rest of society let it happen, but "persons of Japanese ancestry" also let it happen. JACL and other community organizations advocated peaceful compliance with the U.S. Army's exclusion orders as the best way to demonstrate the "loyalty" of "all persons of Japanese ancestry". Yes, the exclusion orders were racist to the core. Even then, they were regarded in not a few legal circles as unconstitutional. Yet the racists had their way. So peacefully did "the Japanese" comply with the orders that General DeWitt, who issued them, and the Secretary of War, who representing the President of the United States sanctioned them, thanked "the Japanese" for their cooperation. Yes, the assembly centers and relocation camps were enclosed and guarded. And yes, permission was required to leave. But leave many did, and resettle elsewhere. For the camps were never "prisons". And no one was sent to a camp for punitive reasons. Calling the camps "prison camps outside the normal criminal justice system" is to totally mispresent historical facts. As much as "evacuation" and "relocation" smack of banal bureaucratese, they accurately describe the purpose of the removals -- to compel "all persons of Japanese ancestry" residing in the west coast exclusion zones to move to, and resettle in, localities to the east of the exclusion zones. Should federal courts have immediately declared the exclusion orders as illegal? Yes. Should JACL and other citizen groups have committed themselves to protesting the exclusion orders and peacefully resisting them? Yes. Should more "persons of Japanese ancestry" have followed the leads of Minoru Yasui and others who challened the curfew and exclusion orders through acts of civil disobedience? Yes. Should 21st-century historians of the exclusion and removal of "persons of Japanese ancestry" from the west coast endeavor to write more honestly about what happened, without muddling historical facts with "critical" ideology? Yes. Do words matter? Yes -- because facts matter. | ||||