M. P. Shiel's yellow peril trilogy

Shantung crisis, Russo-Japanese War, and China's revolution

By William Wetherall

First posted 15 July 2007

Last updated 2 September 2025

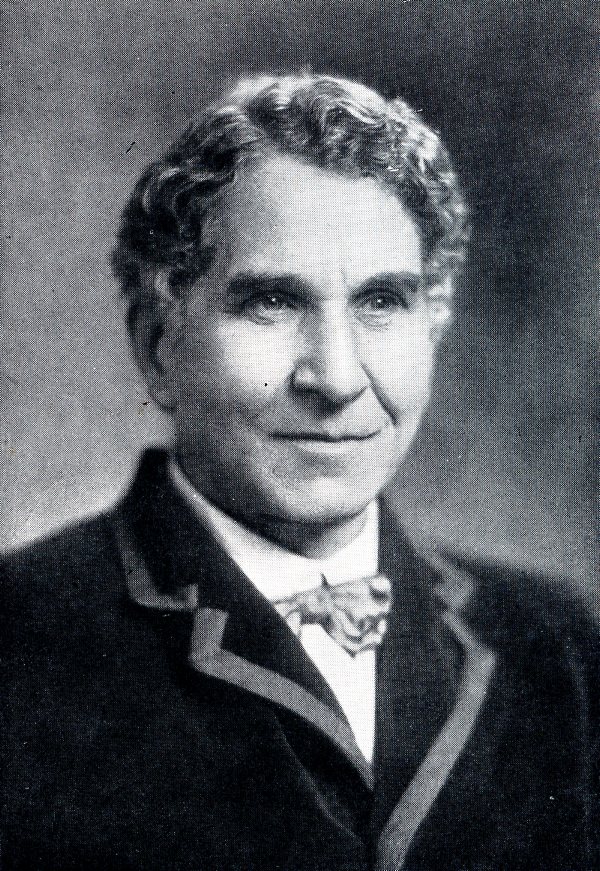

M. P. Shiel (1865-1947)

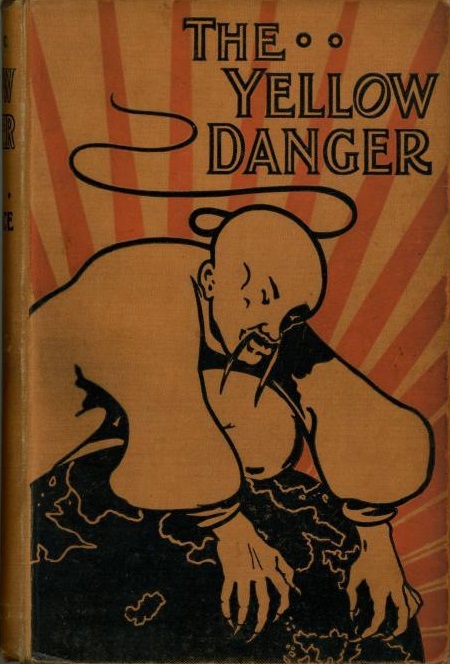

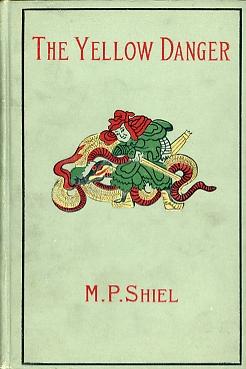

M. P. Shiel, The Yellow Danger, 1898 (Murders of German missionaries in Shantung, 1897)

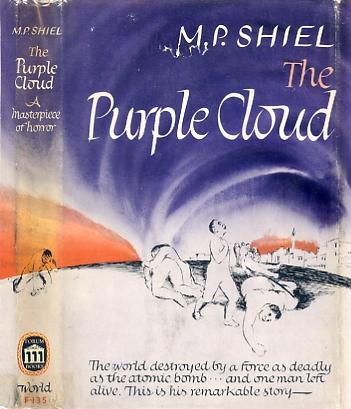

M. P. Shiel, The Purple Cloud, 1901 (An inexorable force destroys mankind)

M. P. Shiel, The Yellow Wave, 1905 (Russo-Japanese War, 1904-1905)

M. P. Shiel, The Dragon, 1913 (China's Revolution, 1911-1912)

aka The Yellow Peril, 1929 (China's Revolution, 1911-1912)

Shiel studies

A. Reynolds Morse, editor, Shiel in Diverse Hands, 1983 (A Collection of Essays)

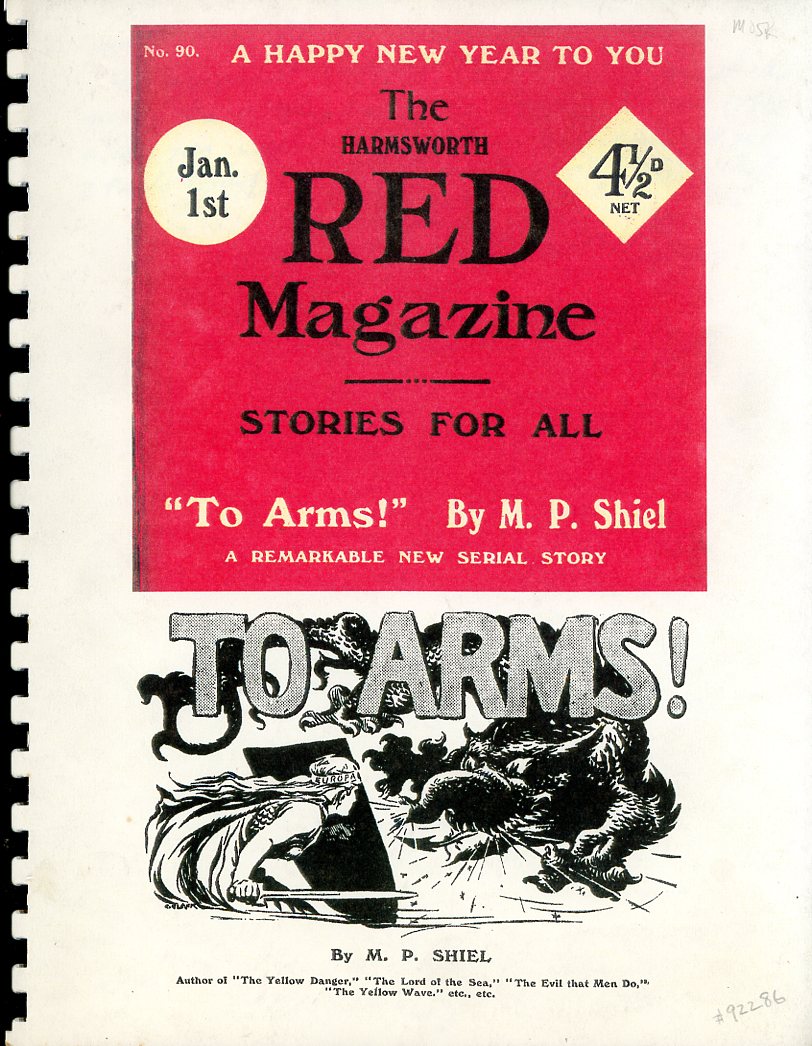

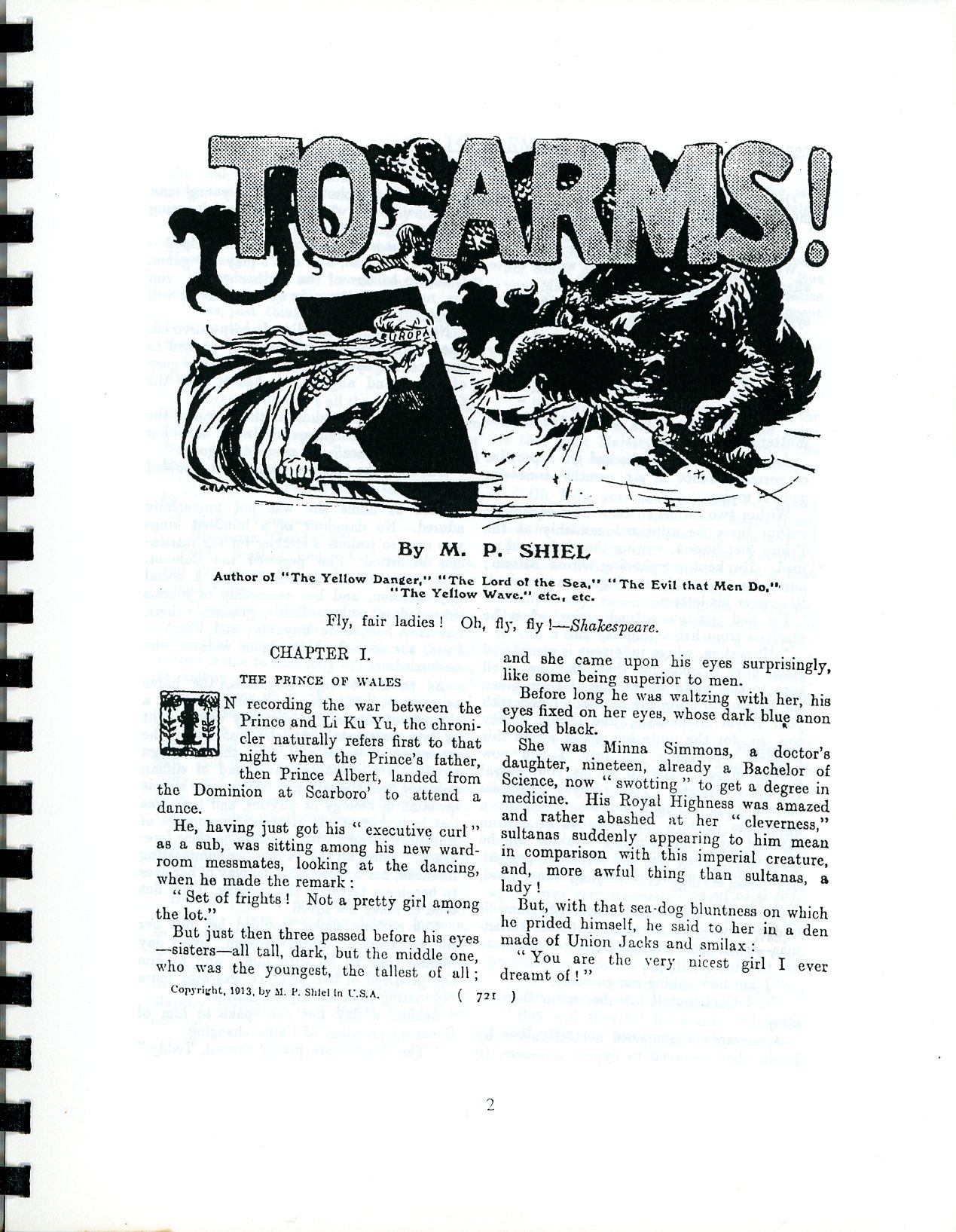

John Squires, editor, "To Arms!", 1995 (The original Serial Publication of The Dragon)

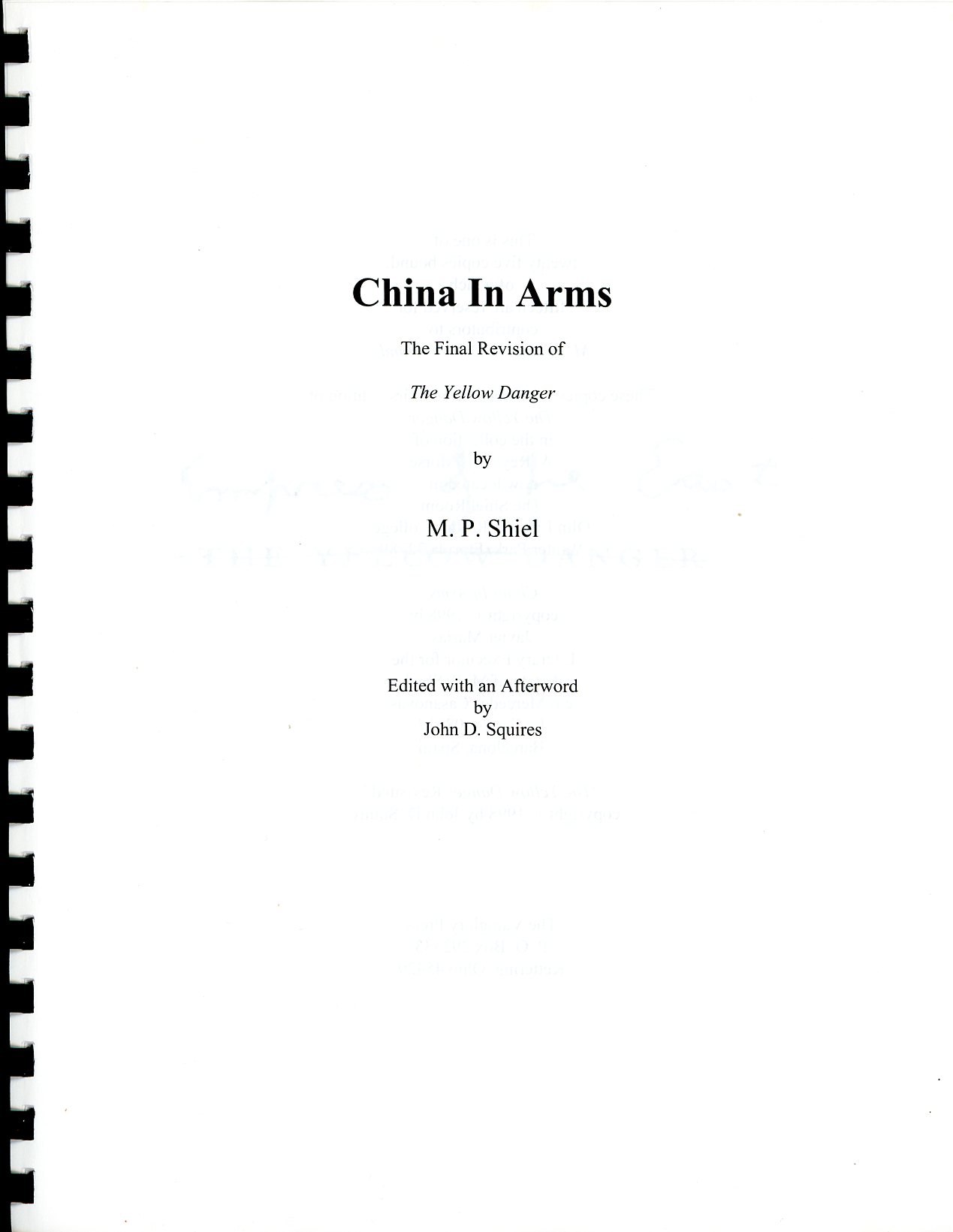

John Squires, editor, China In Arms, 1998 (The Final Revision of The Yellow Danger)

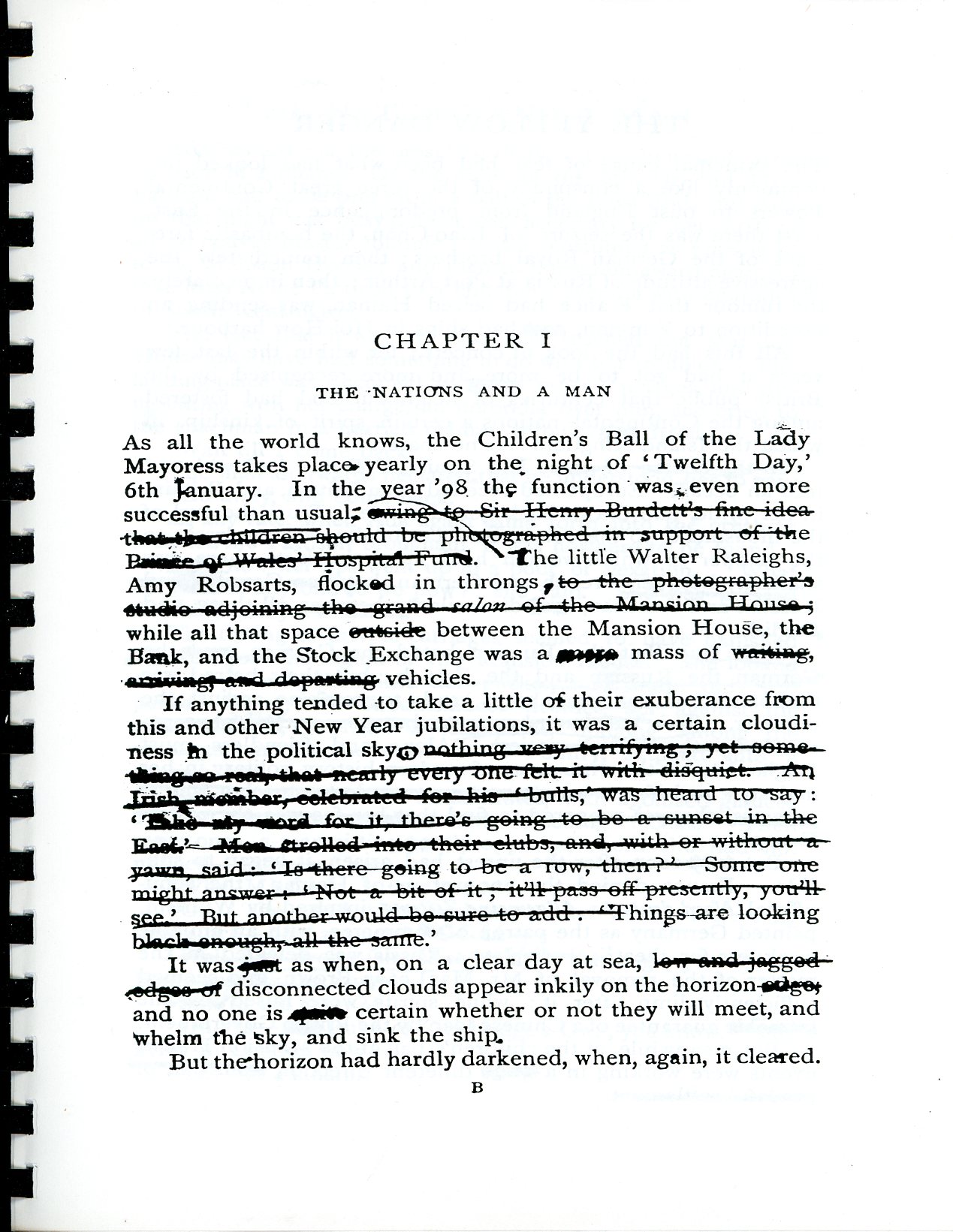

Alan Courtney Tytheridge (1889-1959), Japan's first Shielian

Born in England, raised in New Zealand; settled in Chigasaki, buried in Yokohama

Shiel in Japanese

Mystery fiction boom after Pacific War stirs interest in Shiel's pre-Holmes stories

M. P. ShielMatthew Phipps Shiell (1865-1947), better known as M. P. Shiel (rather than Shiell), was a British writer of fantasy and science fiction, and futuristic, romantic, and adventure stories, many of them involing civil and other wars. As such, he was arguably the most prolific writer of alarmist "yellow peril" novels straddling the end of the 19th and the start of the 20th centuries. He would continue to contribute to the yellow peril genre into the 1920s and 1930s, as he revised earlier titles and wrote new ones. Shiel was born in 1865 in the British West Indies to an Irish Catholic mothers and a father who is is thought to have been "the illegitimate child of an Irish Customs officer and a female slave" (Wikipedia (22 July 2024). He educated at Harrison College, a grammar school in Barbados. After moving to England in 1885, he worked as a teacher and translator, and began writing short stories for popular British magazines. Decades before Shiel died, many critics remarked about the literary quality of his prose, his prowess with the English language, his ability to turn a striking, beautiful, memorable phrase. This prompted even journalists based outside English-speaking countries, such as Alan Tytheridge, writing for Tokyo Nichi-Nichi in Japan in 1924, to introduce Shiel as "an uncrowned lord of language", by way of "acquainting Japanese readers in advance with a name which may presently be world-famous" (Tytheridge 1924, see below). I have focused here on Shiel's "yellow peril trilogy" as I have called. I have also featured his his best known novel, about a different kind of peril, which he published a couple of years after the first yellow peril title. I have also introduced -- under the title "Shiel studies" -- some interesting works produced by professional collectors, editors, and fans of M. P. Shiel after his death in 1947. Yellow peril as "guiltless ignorance"While several of M. P. Shiel's early novels are categorically "yellow peril" stories, it is not clear that he himself was a die-hard ideological yellow perilist. He wrote the yellow peril titles at a time he was hacking his way through life, writing stories suggested by editors in the United Kingdom, set in exotic places, to titillate people who read them to escape from the real world. One can thus argue that Shiel intended only to spin fantastic tales of imagination, reflecting popular concerns about current events, but not depict the world as it really was -- especially the world in Asia, which he knew only through reading -- hence himself could not have really known. In a chapter titled "Of Writing" in a collection of Shiel's writings published 3 years after his death, he clearly saw writing as a literary effort to tell a story that would engage the reader's imagination and "enlarge your [the reader's] consciousness of the truth of things" (Shiel 1950, page 58, in Morse 1983, page 465, see below). Shiel's essay on writing ends with a remark to the effect that writer will be respected, "since our will is ever right and our ignorance guiltless" (Ibid., Shiel 1950, page 94, in Morse 1983, page 483). I take to mean that readers are supposed to trust that a writer of fiction is expected to make them think while entertaining them -- but not necessarily educating them. In other words, readers are not supposed to enter fictional worlds expecting to find "facts" and "truths" about the real world -- whatever that might be. And a writer of fiction who promises to enlighten readers with "facts" and "truths" about the human condition is selling self-deception in the form of literary snake oil. Willaim Wetherall |

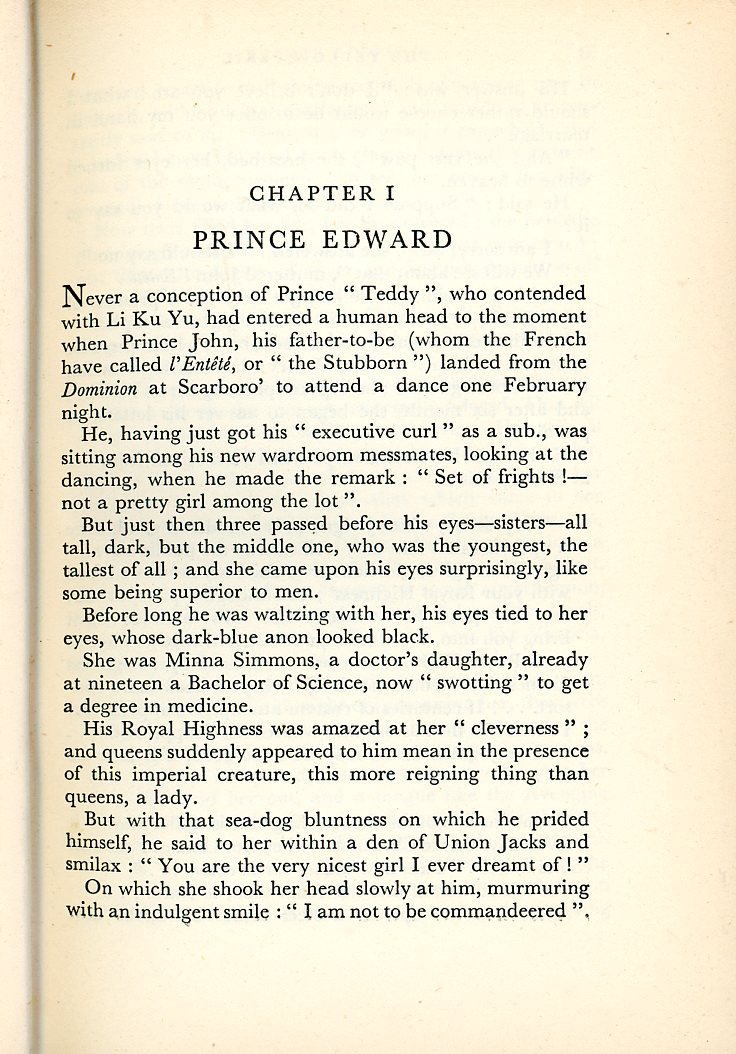

The Yellow Danger1898 British editionM. P. Shiel A later UK edition was published by C. Arthur Pearson in 1908. 1899 American editionM. P. Shiel R. F. Fenno later brought out a paperback edition (date unknown). The 1899 U.S. edition in Yosha Bunko opens with a very dramatic appraisal of British concern about the implications of the Triple Intervention for Britain's position in China, shortly after the Japan's victory over China in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895 (pages 7-8). CHAPTER I [ first graphs omitted ] It was just as when, on a clear day at sea, low and jagged edges of disconnected clouds appear inkily on the horizon-edge, and no one is quite certain whether or not the will meet, and whelm the sky, and sink the ship. But the horizon had hardly darkened, when again, it cleared. The principle cause of fear had been what had looked uncommonly like a conspiracy of the three great Continental Powers to oust English from predominance in the East. First there was the seizure of Kiao-Chau, the bombastic farewells of the German Royal brothers; then immediately, the aggressive attitude of Russia at Port Arthur; then immediately the rumor that France had seized Hainan, was sending an expedition to Yun-nan, and had ships in Hoi-How harbor. All this had the look of concert; for within the last few years it had got to be more and more recognized by the British public that centuries of neighborhood had fostered among the Continental nations a certain spirit of kinship, in which the Island-Kingdom was no sharer. [ one graph omitted ] It is true that the Russian hated the German, and the German the Russian and the French; but their hatred was the hatred of brothers, always ready to combine against the outsider. This had begun to be suspected, then recognized, by the British nation. Alone and friendless must England tread the winepress of modern history, solitary in her majesty; and if ever an attempt were made to stop her stately progress, she was prepared to find that her foe was the rest of Europe. John D. Squires commentaryYellow Danger as published in London and New York was a much shortened version of the series of stories that Shiel was commissioned to write under the title The Empress of the Earth in the magazine Short Stories from 5 February to 18 June 1898, according to John D. Squires, in his 1998 commentary on the genesis, birth, and aging Yellow Danger. Squire's essay begins as follows (Squires 1998, page 353, see below; italics in original; notes omitted). This note is being written in the closing days of 1998 to reintroduce a novel originally written in haste as a serial in 1898. The Yellow Danger was commissioned by Peter Keary [Note 1] in the closing days of 1897, as Shiel told us in "About Myself," "When some trouble broke out in China..." [Note 2] and appeared weekly in Short Stories from 5 February - 18 June 1898 under the title The Empress of the Earth. [Note 3] The weekly serial interwove contemporary personalities and events from each previous week's current events into a fantasy of world war predicated on a racial slight and the obsessive love of a Sino-Japanese mastermind for an English nursemaid. [Note 4] The public loved it and within weeks of the first installment Pearson was asking Shiel to string the serial out. On February 26, 1898 Shiel wrote Grant Richards [Note 5]. I originally undertook to make it 70,000 words: then Pe[a]rson [per penciled correction in received Yosha Bunko copy] writes to ask if I will make it 100,000 words; then comes a telegram: can I make it 150,000 words. What I intend to do is this. I shall make it 150,000 words for them, but 50,000 of this will be merely for the sake of money. The book will consist of 100,000 words which is quite enough. [Note 6] True to his word, the Grant Richards edition published in July 1898 was only two thirds the length of the serial. Shiel made some further revisions to the Grant Richards text at the insistence of his U. S. publisher, R. F. Fenno, for the American edition published in 1899. These consisted primarily of deleting some anti-American comments from earlier sections and completely rewriting the closing chapter, "The Black Spot". On 7 July 1899 Shiel wrote Richards, "By the way, I re-wrote the last ch. Of [sic] T. Y. D. especially for American Publication but we don't care now I suppose." [Note 7] Apparently not, for none of the subsequent English reissues of the novel incorporated these revisions. [Note 8]. The Yellow Danger made Shiel 's popular reputation and was almost certainly the most commercially successful of the twenty books published during his first creative period, 18891913. Following the commercial failure of The Dragon 9 in 1913, Shiel apparently turned away from novels. For most of the next decade he published only a few short stories and wrote at least five plays, but could get none of them staged. The Yellow Danger (1898) includes a chapter called "The Yellow Terror" (Chapter XXVIII, pages 291-302, 1899 U.S. edition). The "yellow menance" was another contemporary expression of concern about global domination by Orientals. The Yellow Danger was not -- as some writers claim -- an earlier edition of The Yellow Peril (1929). The latter was a retitling of The Dragon (1913), for which see below. This later novel includes a chapter called "The Yellow Deluge" (Chapter XXIV, pages 318-344), yet another "yellow peril" metaphor. |

The Purple Cloud (1901)M. P. Shiel There have many many editions of this books, including the one shown here. M. P. Shiel This 1946 edition is actually a revised edition, which was first published in 1929. The original text has become the basis of several recent editions, but apparently only the 2012 Penguin classic edition also incudes the original art work. As the novel is now in public domain, many people have brought out editions through self-publishing houses. Revised editions

London: Victor Gollancz Ltd., 1929 Revived original editionLondon: Penguin Classics, 2012 "the atomic bomb"The Purple Cloud is widely regarded as one of the first and finest end-of-the-world fantasies. Cover blurbThe world destroyed by a force as deadly as the atomic bomb . . . and one man left alive. This is his remarkable story." Front flap blurbThe Purple Cloud is an adventure into the realm of the Unknown. It proposes the question: what would happen if some inexorable force were to destroy all mankind? -- and it answers that question. A strange vapour, far more deadly than the atomic bomb, passes over the earth, and leaves death in its wake. Only one man escapes the cloud, a man destined to spend his life wandering throughout a world of the dead. This is his remarkable story. While atomic bombs are featured in fiction before World War II, these references to "the atomic bomb" clearly allude to the bombs dropped by the United States on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, barely a year before the release of this edition, and fresh in the memories of most prospective readers. Japanese translationA Japanese translation of The Purple Cloud was translated into in 2018. See Shiel in Japanese (below) for particulars. |

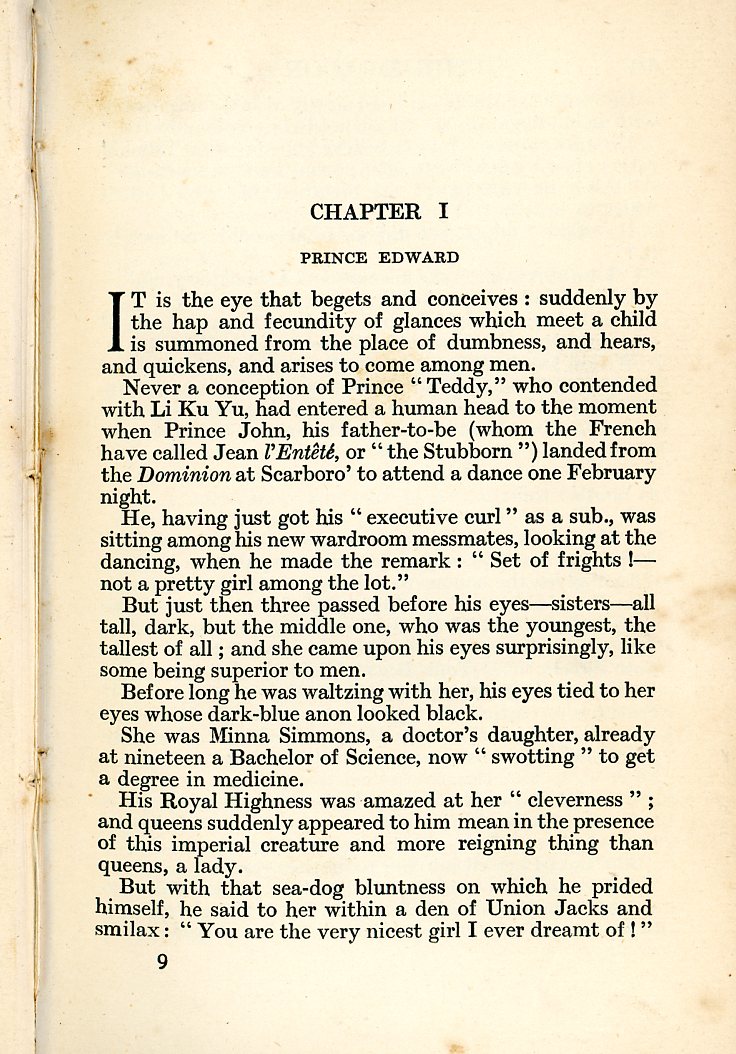

The Yellow Wave (1905)1905 London editionM. P. Shiel This copy of The Yellow Wave has a frontispiece showing Yoshio's Russian friend being taken as a prisoner of war by a Japanese soldier in the heat of battle. The frontispiece is protected by a sheet of tissue paper recto to it. Notice the mispelling of author's name on title page while the spellings on the dark red embossed front cover and spine are correct. The Toronto edition, of a similar design but with un-embossed dark blue boards, shows the "Sheil "mispelling on the front cover and spine as well as on the title page. Notice also that the title page of the copy in Yosha Bunko says "Author of "The Yellow Peril" "The Evil That Men do" / "Lord of the Sea" "Cold Steel" Etc Etc". This is puzzling, for while the other titles were published in respectively 1904, 1901, and 1900, "The Yellow Peril" -- as a retitling of The Dragon (1913) -- was not published until 1929. Here the title is probably an error for "The Yellow Danger", published in 1898. 1906 Toronto editionM. P. Shiel The backdrop of this novel is the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905. Japan was victorious, and the ink on the Treaty of Portsmouth had barely dried when The Yellow Wave came out. The treaty (1) gave Japan the southern half of Sakhalin, which became the Japanese territory and later prefecture of Karafuto, (2) transferred to Japan Russia's lease from China of Liaotung peninsula, including Port Arthur, which Japan had received from China as partial settlement to the Sino-Japanee war of 1894-1895 then been forced to return to China by the Triple Intervention of Russia, Germany, and France in April 1905, and (3) recognized Japan's interests in the Empire of Korea and Manchuria, which was part of China by then was largely beyond the reach of effective Chinese control and jurisdiction. Chapter I, The Tiger-Hunters, opens like this (pages 7-10, (parenthesis) in original, clarifications in [brackets] mine, floating rather than tight-left colons and semi-colons transcribed as shown in the text). CHAPTER I THIS name of "Tiger-hunters," taken by the well-known Society started in Tokio four months before the [Russo-Japanese] war [of 1904-1905] was borrowed from a gang of Korean bandits with whom the Japanese society had nothing to do. There are no tigers in Japan, but there are in Korea; and the Japanese have a saying that " to fight with Koreans is to fight with tigers," because all the Koreans run away, and only tigers remain to be dealt with. This is classic Shier -- generally clear, crisp, and colorful as he sets the contemporary geopolitical stage for his imaginary tale and draws the reader into it convoluted plot. Wikipedia's article on M. P. Shiel, which has proven to be very reliable on most points for which I have independent evidence (see Shiel studies below, says this about The Yellow Wave (first seen 15 July 2007, seen again 23 July 2024) Shiel returned to contemporary themes in The Yellow Wave (1905), an historical novel about the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905. The novel was a recasting of Romeo and Juliet into the on-going war with leading families of the two nations standing in for the feuding Capulets and Montagues of Shakespeare's play. Shiel modeled his hero on Yoshio Markino (1874-1956) [sic = 1870-1956], the Japanese artist and author who lived in London from 1897-1942. In February 1904 Shiel had offered to Peter Keary to go to the front as a war correspondent with letters of introduction from Markino. He may have met Markino through Arthur Ransome who dedicated Bohemia In London (1907) to Shiel and used him as the model for the chapter on "The Novelist." Faced with declining sales of his books, Shiel tried to recapture the success of The Yellow Danger when China and Sun Yat-sen returned to the headlines during the Chinese Revolution of 1911-1912. Though a better novel in most respects, The Dragon (1913), serialized earlier that year as To Arms! and revised in 1929 as The Yellow Peril, failed to catch the public's interest. As the hero of the story had oddly predicted, Shiel turned away from novels for ten years. Yoshio Markino (ヨシオ・マルキーノ Yoshio Marukiino 1870-1956) was Makino Yoshio (牧野義雄) when he left Japan for San Francisco in 1893. He later anglicized the alphabetic transliteration of his name, apparently to force readers to say "Ma" as in "mark" rather than in "may". In 1923, he married a French woman named Marie Biron (マリ−・ビロン), and they lived in New York and Boston for a while. In 1927, he returned to London alone, and the following year they were formally divorced -- without children. Biron claimed that the marriage had never been consumated. |

||||

The Dragon (1913)

|

||||||||||||||

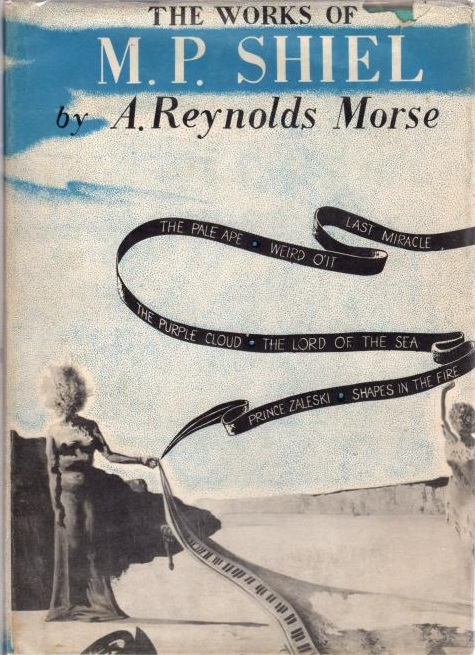

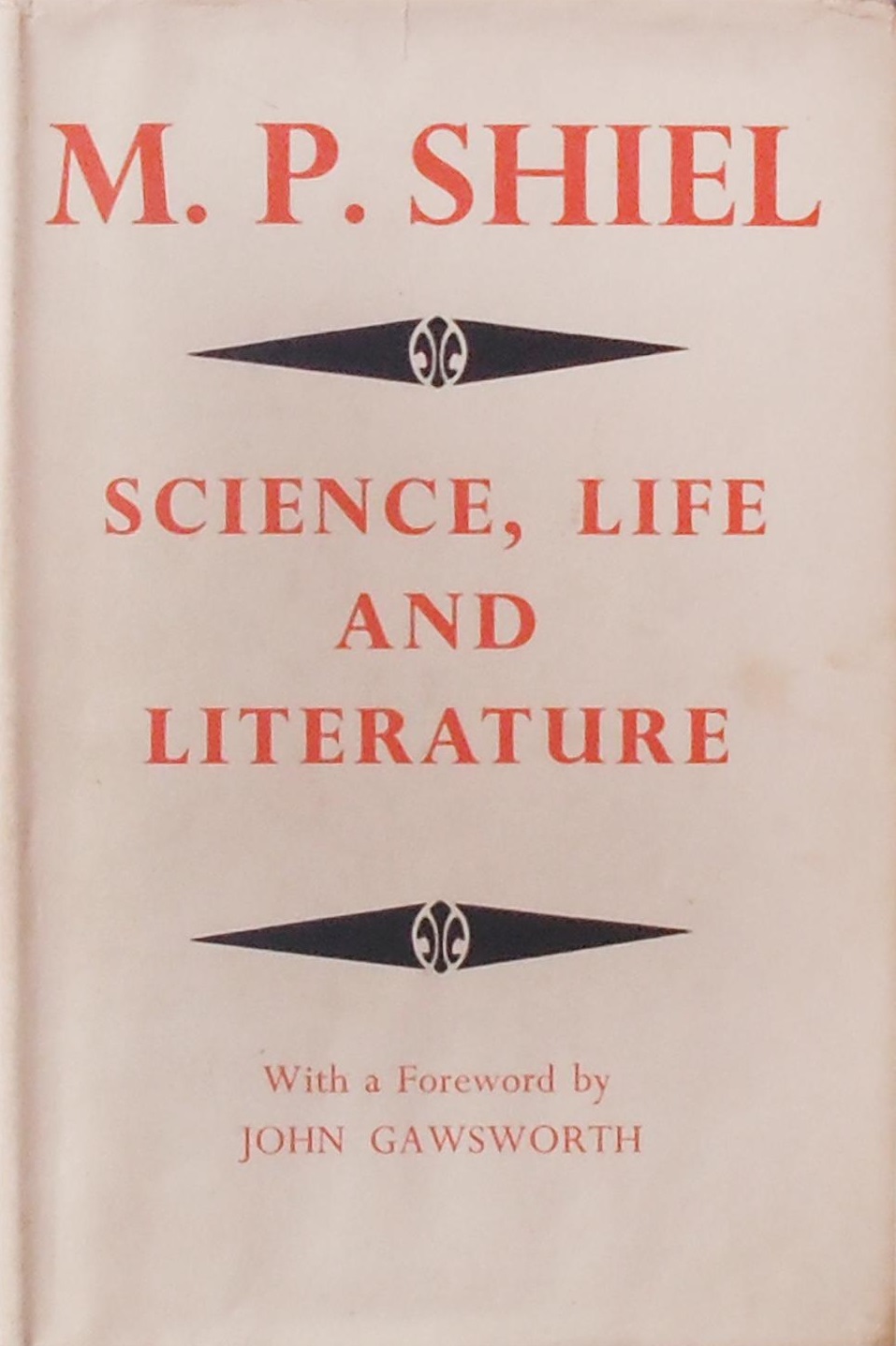

Shiel studiesThe death of M. P. Shiel in 1947 left in its wake a flurry of publications, including The Best Short Stories of M. P. Shiel, brought out in 1948 by Victor Gollancz Ltd., the London publisher of many of his novels. More importantly for students of Shiel, however, were the biographical and autobiographical accounts of Shiel's life and writings -- also in 1948 The Works of M. P. Shiel by A. Reynolds Morse, then in 1950 Science, Life and Literature by Shiel himself, completed shortly before his death with instructions that it be published. The most ardent fan, collector, and student of Shiel's works was Albert Reynolds Morse (1914-2000), an American businessman and philanthropist, who with his wife, Eleanor Reese Morse (1912-2010), also a philanthropist, founded the Salvador Dalí Museum in St. Petersburg, Florida. Both were heirs to family businesses and fortunes, and Dalí friends and collectors. Morse would edit the 4 volumes of Shiel in Diverse Hands, including Volume IV, A Collection of Essays (Morse 1883), reviewed below. Morse 1948A. Reynolds Morse In the front of the book is a "Notice of Limited Edition" statement, which says that 1000 copies were printed as a memorial to M. P. Shiel by the Fantasy Publishing Company of Los Angeles and Mr. and Mrs. A. Reynolds Morse of Cleveland, and that each copy is numbered. But the "This is number _____" line in the copy shown here is blank. And all booksellers offering copies describe the book as an "unnumbered" limited edition. The dust jacket design is attributed to Salvador Dali, based on a Dali painting titled "Three Young Women Holding in Their Arms the Skins of an Orchestra". The volume includes a revised edition of M. P. Shiel's "About Myself". Shiel 1950M. P. Shiel The volume includes "Of Myself" and other essay essays, including the Of Writing collected in Morse 1983 (below). An updated edition of this book appears to have been published in 1980. The earlier edition included a hand-tipped frontispiece portrait of Shiel. The dust jacket includes this blurb. Shortly before his recent death M. P. Shiel handed this book in its final draft to his first bibliographer and last collaborator, the poet John Gawsworth, with injunctions to "see it to press"." Hence the volume includes a foreward by the British writer, poet, and anthologist John Gawsworth (1912-1970), whose legal name was Terence Ian Fytton Armstrong or T. I F. Armstrong. Gawsworth is perhaps best known -- if known at all -- as M. P. Shiel's literary executor. If rumors can be believed, he made Shiel an object of cultist worship. John Sutherland reportedly wrote in Lives of the Novelists that "the excessively minor poet John Gawsworth" kept Shiel's ashes "in a biscuit tin on his mantelpiece, dropping a pinch as condiment into the food of any particularly honoured guest" (Wikipedia (John Gawsworth, viewed 24 July 2024). Sutherland 2011, 2012John Sutherland This book, by the British literature scholar, author, and newspaper columnist John Sutherland (b1938), contains essays on the lives of 294 fiction writers culled from past 400 years of literature. Sutherland, a specialist in Victorian fiction, also has a penchant for mystery fiction and genres that would not generally be included in lists of the best titles in history. That M. P. Shiel made Sutherland's 294 cut signifies that Sutherland saw him as more than just a flash in the pan of hundreds of thousands, perhaps a million or more novelists who graced the pages of works published during the four centuries. Profile Books in London promotes Sutherland's book, first published on 27 October 2012, like this (profilebooks.com). This is the most complete history of fiction in English ever published - now in paperback. Arranged in chronological order, the novelist's lives are opinionated, informative, frequently funny and often shocking. Professor Sutherland's authors come from all over the world; their writings illustrate every kind of fiction from gothic, penny dreadfuls and pornography to fantasy, romance and high literature. The book shows the changing forms of the genre, and how the aspirations of authors to divert and sometimes to educate their readers, has in some respects radically changed over the centuries, and in others -- such as their interest in sex and relationships -- remained remarkably constant. It appears that M. P. Shiel -- never mind his reputation among activist scholars opposed to novels that appear to rank races on a scale of superiority -- is in good company, as a story teller and wordsmith. Like music -- which is is good if it is good, regardless of its genre or the character of its composer -- literature is good if it is capable of holding a reader spellbound with a fine plot unfolded with fine prose. Literature is more about the story than the message -- such as the message may be to readers who image that there is one. William Wetherall |

Morse 1983Shiel in Diverse HandsEdited with notes by A. Reynolds Morse A second title page describes this collection of essays as follows. Shiel In Diverse Hands, Volume IV of The Works of M.P. Shiel, And including both versions of "On Reading" by M. P. Shiel, Edited with notes by A. Reynolds Morse / The title for this collection of essays on Matthew Phipps Shiel (1865-1947) was suggested by Sam Moskowitz I acquired this volume in July 2007, with the following two volumes, as a set of 3 volumes of studies of Shiel's stories and manuscripts, from an antiquarian book dealer in Elizabethtown, New York. They cost $199 plus shipping to Japan -- in the days when there were affordable options like "sea mail" and "book rates". All the volumes were published in extremely limited editions -- only 25 copies of the 2nd and 3rd volumes, 15 of which were reserved for contributors to the 1st volume, which was privately published and distributed by one of the contributors, John D. Squires. From the internal evidence of the inscription to "Sam" by "JDS", I would guess that all 3 volumes came from the personal collection of Sam Mosowitz. And he seems to have been given the copies by Squires. All three men -- A. Reynolds Moses (1914-2000), Sam Mosowitz (1920-1997), and John D. Squire (1948-2012) -- were noted "Shielians", as world authorities on M. P. Shiel are dubbed. 29 essaysOf particular interest to me was the first of the 29 essays by Sheil fans, as it was published in the Tokyo Nichi-Nichi in 1924. Titled "An Uncrowned Lord of Language: An Appreciation of the Literary Work of M.P. Shiel", It ran from 16 to 24 July 1924 in 8 parts in as many installments, in the daily broadsheet Tokyo Nichi-Nichi, and was signed by an "Alan Tytheridge". Editor A. Reynolds Morse expressed his gratitude, on behalf of all Shielians, to fellow Shielian Tatsuo Yamada in Japan, who found and recovered Tytheridge's article from newspaper archives in Japan. Tytheridge's full identity remained fuzzy to both Yamada and Morse as of 1983, when Morse published the collection of essays on Shiel as Volume IV of Shiel In Diverse Hands. Since then, the Internet has facilitated finding primary records of famous and unknown people from all walks of life. For an overview of what I was able to find on Ancestry.com, Newspapers.com, and family history blogs, see Alan Tytheridge (1889-1959) second from the bottom of this page. |

Squires 1995"To Arms!"M. P. Shiel The colophon makes the following disclosures. This is one of twenty five copies bound by J. D. S. [John D. Squires] Books, P. O. Box 67, MCS, Dayton, Ohio 45402, for private circulation only to contributors to M. P. Shiel in Diverse Hands These copies [of the original serial publication of The Dragon] were made from a partial run of The Harmsworth Red Magazine in the collection of A. Reynolds Morse now located in The Shiel Room, Olin Library, Rollins College, Winter Park, Florida 32789 An inscription in blue ink on the front free fly reads as follows. Sam, "Sam" is the "Sam Moskowitz" who contributed the title "Shiel in Diverse Hands" to four Shiel volumes edited by A. Reynolds Morse (1914-2000), which concluded with the 1983 collection of essays on Shiels. Sam Moskowitz (1920-1997), an American, was a youthful fan and collector of science fiction, who organized science fiction conventions in his teens. He went on to be a major critic and historian of science fiction, and as an editor, he revived a number of early titles, incuding a few by William Hope Hodgson (1877-1918), a British writer of horror, fantasy, and science fiction. I was unable to decipher the currsive initials -- until I noticed the same scribble over the name of John D. Squires on the title page of his commentary, "The Yellow Danger Revisited: An Afterword to M. P. Shiel's China in Arms" (see Squires 1998 below). The set of three volumes, including this volume, appears to have been from Moskowitz's library. The penciled insertion of "a" into "Person" to correct it to "Pearson" in Squire's commentary may well be that of Moskowitz if not Squires. See citation of the first few graphs of the commentary under Shiel 1898 (above). |

Alan Courtney Tytheridge (1889-1959)Japan's first ShielianBorn in England, raised in New Zealand;

|

Chronology1889-06-15/07-22 (age 0) A Christ Church baptismal record for the County of Surrey shows that "Alan Courney", son of Robert Walter & Lucy Tytheridge of Epsom, having been born on 15 June 1889, was baptised on 22 July 1889. His father is described as a "Medical Practitioner" (Ancestry.com) Walter Robert Tytheridge 1891 (age 1) An 1891 census for the Civil Parish of Epsom in Surrey shows Alan C., age 1, the son of Walter R. Tytheridge, 41, a "General practitioner", and his wife Lucy, 39 (Ancestry.com). 1895-10-18 (age 6) A passenger manifest shows the Tytheridge family -- Dr. Tythridge, a Doctor, with Mrs. Tytheriged, a Lady, and Master A. Tythridge, a Son, age 6, as cabin passengers aboard the steamer Richmond Hill, which had sailed from London on 18 October 1895 and was bound for Wellington, New Zealand (Ancestry.dom). 1915-06-28 (age 26) The Honolulu-Star Bulletin reported on 28 June 1915, under the headline "Editor of Fiji Paper Coming in September", as follows (Monday, page 3, Newspaper.com, [bracketed] clarifications mine). A. C. [Alan Courtney] Tytheridge, editor of the Fuji Times at Suva, has written to the Promotion Committee that he will visit Honolulu sometime in September. Mr. Tytheridge will spend several weeks in the islands securing articles on Hawaii for his paper, and will go from here to San Francisco to attend the exposition. 1915-10-15 (age 26) "Tytheridge Allan C." [sic], Age 26, Sex male, Citizen England, arrived at the port of Honolulu, T.H., on 15 October 1915, aboard the steamer Makura. (Ancentry.com) 1916-10-21 (age 27) The Daily Standard, a Queensland, New Zealand paper, included the following brief (Saturday, page 9, Newspaper.com). Alan Tytheridge, a well-known New Zealand journalist, who has been in America for some time, was recently appointed pianist and accompanist to a noted Portuguese cellist and violinist, and they are shortly to tour Japan. 1934-07-26/08-04 (age 45) "List or Manifest of Alien Passengers for the United States Immigration Officer at Port of Arrival" shows "Tytheridge Alan Courtney" arriving at the port of Honolulu in T. H. [Territory of Hawaii[) on 4 August 1934 aboard the S.S. "Taiyo Maru", having sailed from Yokohama on 26 July 1934. He is Age 45 [born c1889], Sex Male, single, teacher, British by "Nationality (Country of which citizen or subject)", English by "Race or people", born in Epsom Surrey in England, bearing a passport issued in Yokohama on 13 July 1934, "Last permanent residence" Chigasaki in Kanagawa-ken in Japan, standing 5 feel 11 inches, Fair Complexion, Bwn. Hair, Drk. grey Eyes (Ancestry.com). The manifest states that Tytheridge had previous resided in the United States in San Francisco from August 1915 to September 1916, supporting 1934-08-05 (age 45) The Honolulu Sunday Advertiser reported on its "Travel-Shipping Waterfront News Page" on 5 August 1934, that among the 60 passengers arriving on the Taiyo Maru, several had landed in Honolulu, including an "A. C. Tytheridge, professor of University of Commerce, Tokyo, enroute on vacation trip" (Sunday, page 17, Newspaper.com). 1959-10-30 (age 60) A Find a Grave memorial shows Tytheridge buried in "Yokohama Foreign General Cemetery" in Yokohama in Kanagawa prefecture. The headstone reads "Alan C. Tytheridge / June 15, 1889 - Oct. 30, 1959". He died just a few months after turning 70. Foreigners in 19th century Yokohama |

Ann Titheradge and Jenny Stroud

Family historian Ann Titheradge, from Sussex, England, has created a blog devoted to Titheradge Titheridge Tidridge Tytheridge Genealogy. She is a "Titheradge", but includes "Titheridge" as one of several variations of the same family name.

Ann Titherage explains her interest in the family name like this.

My interest in family history began when I married and acquired this unusual surname "Titheradge". People kept commenting "Never heard of that name before", "How do you spell that?", "where does that name come from?" This began my interest in the family name and its variants (Titheridge, Titheradge, Tytheridge, Tidridge, Titherage, Tutheridge etc.).

My husband, Mike, and I have been researching the family name for 30 years. We are members of the Sussex Family History Society and Hampshire Family History Society. We have also registered the name with the Guild of One Named Studies.

Ann Thieradge was aided in her research on Alan Tytheridge by Jenny Stroud, described as his second cousin twice removed. Their collorative research resulted in a fairly detailed chronological sketch of Alan Tytheridges's life, posted in 4 parts in July and August 2029.

Alan Courtney Tytheridge

By Ann Titheradge and Jenny Stroud

Part 1 Musician and Linguist 1889-1916 (Monday 15 July 2019)

Part 2 Life in Japan 1916-1939 (Sunday 21 July 2019)

Part 3 Japan at War 1941-1945 (Saturday 27 July 2019)

Part 4 Alan Remembered 1945-1959 (Sunday 4 August 2019)

Eric Stewart Bell

Eric Stewart Bell was born in Chirstchurch on 21 September 1887 and died in Japan, possibly in Numazu, on 11 October 1964 a month shy of 77. The Christchurch ArchivesSpace website, of Christchurch City Libraries in New Zealand, posts the following account of his life in Japan (viewed 24 July 2024, [bracketed] clarifications mine).

Eric Stewart Bell, born 1887, to Charles Stewart and Eve Bell in Christchurch. Eric was educated at Christ College where he sang in the choir. Music was a passion and he went on to conduct several orchestras in the city. He first worked at Milner & Thompson Ltd., then founded his own business, Oriental Arts Ltd., in Cathedral Square.

In 1922 he arrived in Japan. His friend Alan Courtney Tytheridge, who had been a buyer for Oriental Arts Ltd., was already living n Japan. Both men would live out their lives in Japan. In his first year there he lived through the Great Kanto Earthquake. Later he was interned in a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp during World War II. During his 42 years in Japan he taught English at various schools and industrial plants, as well as the University of Mercantile Marine in Shimsu [sic = Shimizu]. For the 15 years before his death in 1964 he taught English in a girls' school in Numazn [sic = Numazu] City which he was instrumental in making a sister school with Christchurch Girls' High School. Obituary, The Press, 12 October 1964, page 11.

The library's archives include photographs, correspondence, and an autography book give him by him by Alan Tytheridge, who inscribed the book "To Eric Stewart Bell with affection, from his friend, Alan Tytheridge. 8 October 1912." The website describes the relationship between Tytheridge and Bell as "Life long friends who met during schooling at Christ's College, played and conducted in orchestras together, and both men taught and lived in Japan for decades."

Excerpts

While bloated with a lot of genealogical boilerplate, the blogs are laced with numerous documented facts and reported information about Alan Tytheridge's life -- which began in English where he was born, shifted to New Zealand where he was educated, then to Fiji, Honolulu, and San Francisco, then back to New Zealand, and finally to Japan, where he lived the larger part of his life, died, and was buried.

Joining Alan in Japan was a New Zealand schoolmate and lifelong friend Scott Stewart Bell (1887-1964). While the two men generally lived apart, neither appear to have married. And Alan is known to have written about homosexuality in Japan.

The following excerpts are foils for comments.

PART 1

Introduction

This is the fascinating life story of Alan Courtney Tytheridge. He was a remarkable man who was a scholar, an author, a musician and a linguist. He lived in four different continents during his life time and lived through an earthquake and internment by the Japanese in World War 2.

Although I have researched Alan's life for many years much of the research presented here must be credited to Jenny Stroud whose research into the life of Alan and the background information is amazing. Thank you to Jenny for giving me permission to use her research and images. Jenny is Alan's second cousin twice removed, related to him via his mother, Lucy Winterbottom. I would also like to thank Graeme Bell and Jenny's Japanese researchers (Miyo and Mizuyo) for the assistance they have given.

Tytheradge and Stroud cite information that appears to come from scans of documents available through a number of on-line genealogy websites, but they do not cite their sources.

PART 3

Kanagawa No 2 Camp

Alan was luckier and was not identified as a spy. On 9 December 1941 Alan was arrested, as a general foreign national, not as a spy, and interned at the Kanagawa No 2 Camp, Yokohama, which was the Yokohama Yacht Club. Both Alan and Eric had their properties taken into the custody of the Japanese government. This would have included their two houses and all their private belongings.

Yamakita Camp

In June 1943 the two camps that both Alan and Eric were in closed and the internees were relocated in the same camp, the Yamakita Camp, also known as the Odawara City Camp. It was in the hills to the south west of Yokohama, with the nearest village 15 minutes away and Yamakita an hours' walk away.

On 10 September the internees in Yamakita Camp were released and Alan and Eric were transported to Chigasaki to Alan's home. Eric was unable to return to his home as it had been sold by the Japanese authorities and was occupied.

In New Zealand on 2 October 1945 a Wellington paper reported than that Eric Bell and Alan Tytheridge and some other New Zealanders were safe following the end of the War in Japan.

These descriptions of the camps are generally accutate. Again, the authors do not cite sources. But many sources, including studies of internment camps, and internee diaries, substantiate their descriptions. It turns out that Alan and Eric shared camps with others I have studied, including John Mittwer (1907-1999), an American, and William Duer (1892-1976) and his son Sydengham Duer (1919-1990), who were British. All three of these men were born in Japan to Japanese mothers. For details on their lives, and interment camp sources that include Alan Tytheridge and Eric Bell, see Internment in Japan at Henry Mittwer (1918-2012): Finding himself in a story not of his making under "Nationality issues" in the "Nationality" section of the Yosha Bunko website.

PART 4

For me the surprise is that both Alan and Eric wanted to stay in Japan after the treatment they received at the hands of the Japanese. Alan obviously loved the country, the civilian Japanese, his Japanese friends and the way of life. He later told a New Zealand friend he regarded Japan as his permanent home and would never leave unless forced to do so by the Japanese authorities.

During his internment Alan's property had been sold by the Japanese government to various owners, but somehow, he was able to return to his house once he was released. Eric was not so lucky as his house was in possession of other people and in October 1945 he wrote to authorities to say he was living in a room at Alan's home but wanted to return to his own place as soon as possible. He eventually moved to a new house further out of Tokyo, on a beach looking across at Mount Fuji.

It took Alan until August 1948 to reclaim his rights to his home and property which had been claimed by the Japanese government during his internment. The restoration of Alan's property was dealt with by the Americans from the General Headquarters of the Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces. Ironically while the Americans were helping him get his property back in Japan, in the USA the government were beginning proceedings to confiscate his bank account with the City Bank of New York. It was in 1950 that the American Attorney General announced in "The Register" that "people viewed as the enemy were to have their assets seized". The "Trading with the Enemy Act" meant Alan was considered as a resident of Japan and a national of a designated enemy country. His American assets were seized by the government and "used for the benefit of the United States." The amount of money lost is unknown.

The worst images of Japanese treatment of prisoners of war have affected (infected) images of the treatment of civilian enemy aliens interned in Japan. On the whole, enemy aliens in Japan were treated fairly well. Conditions somewhat deteriorated toward the end of the war when there were shortages of food and medical supplies throughout Japan, and rationing -- and at times corruption -- affected the supplies of provisions allocated for internment camps. See the article on Alien and native enemies on the Henry Mittwer (1918-2012) page in the "Nationality" section of "Yosha Bunko" website for a look at treatments of enemy aliens in both Japan and the United States.

"

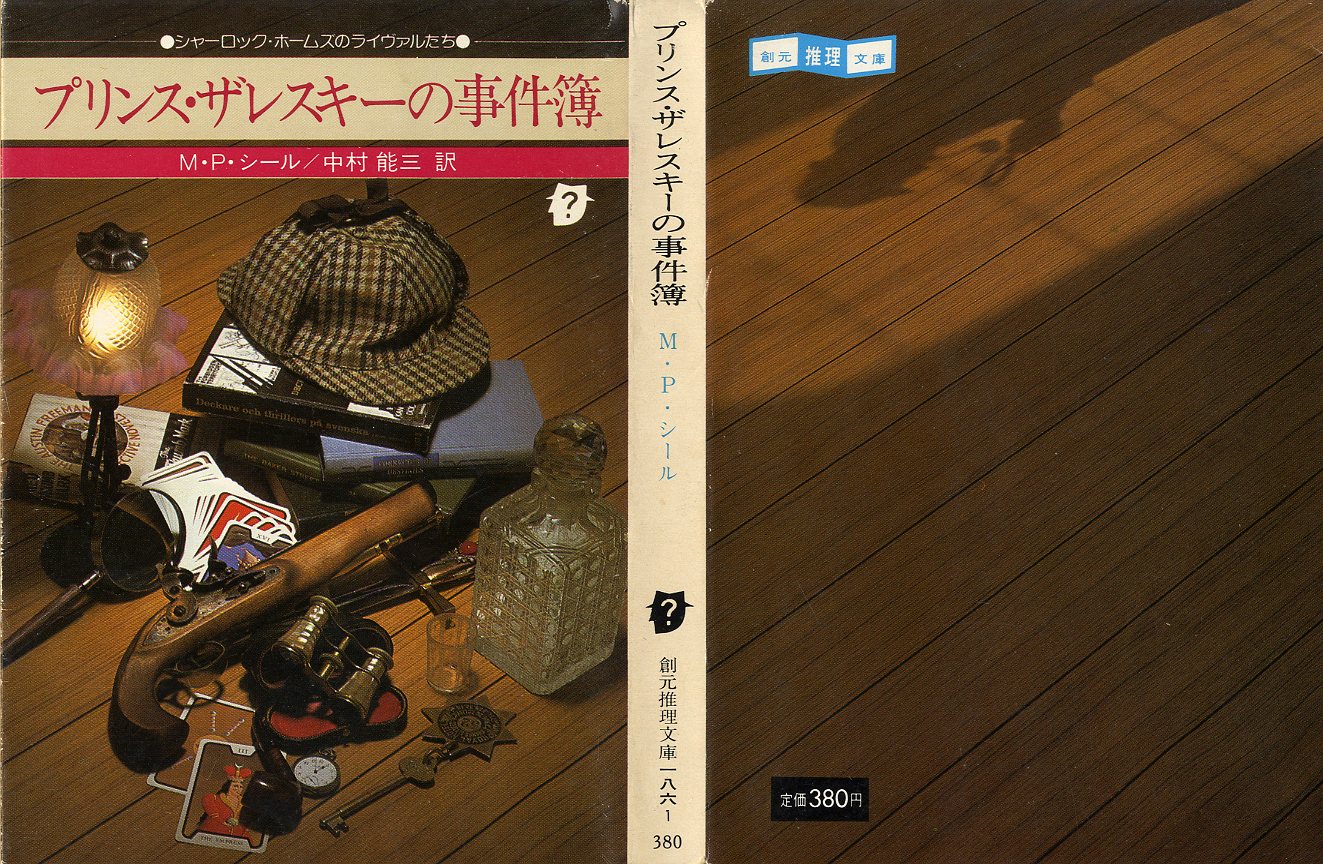

Shiel in JapaneseShiel's novels were not translated into Japanese at the time they were published. Other than the , and I have been able to find only two later translations -- Nakamura Yoshimi's 1981 translation of Prince Zaleski's case book (1885), which is no longer in print -- and Nakajō Takenori's 2018 translation of The Purple Cloud, which as of this writing (2024) remains in print. Shiel 1981 (1885, 1911, 1936, 1945)M. P. シール M. P. Shiel This is a translation of Prince Zaleski and Cummings King Monk, an anthology of Spiel's stories published in 1977 by Mycroft & Moran, Sauk City, Wisconsin. The collection includes the first 3 Shiel's Zaleski stories, which constituted his first book, Prince Zaleski, published in 1885 -- a 4th Zaleski story published 50 years later in 1945 when Shiel was 80 years old -- a commentary on deduction he wrote with John Gawsworth in 1936 -- and 3 Monk stories that were included in Shiel's 1911 collection The Pale Ape and other pulses (London: T. Werner Laurie). Hence the the use of "jikenbo" (事件簿) or "case book" in the Japanese title. The subtitle, "Sherlock Holmes' rivals", comes from the title of the 19-page overview of Shiel's works at the end of the book, focussing on the stories in the book, by Togawa Yasunobu (戸川安宣 b1947). Shiel's stories preceded by 2 years Arthur Conan Doyle's A Study in Scarlet, the first Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson story. Shiel, to the extent that he was influence by other writers, would have been inspired by the legacy of Edgar Allan Poe -- as was Doyle, who was born in 1859 -- 10 years after Poe died, and 6 years before Shiel was born. Most of the following bibliographic particulars were culled from the 19-page commentary at the end of the anthology by Togawa Yasunobu (戸川安宣 b1947), a Sōgensha editor and mystery fiction critic, titled "Shaarokku Hoomuzu no raivaru-tachi: Purinsu Zaresukii to umi no oya Shiiru (シャーロック・ホームズのライヴァルたち:プリンス・ザレスキーと生みの親シール) -- "Sherlock Holmes' rivals: Prince Zaleski and [his] birth-parent Shiel" (pages 345-363). Prince Zaleski storiesThe Race of Orven (1895) The Stone of the Edmundsbury Monks (1895) translated as The S.S. (1895) translated as The Return of Prince Zaleski (1945) translated as Shiel on deductionA Case for Deductuon (1936) translated as Cummings King Monk storiesHe Meddles With Women (1911) translated as He Defines 'Greatness of Mind' (1911) translasted He Wakes an Echo (1911) translated as

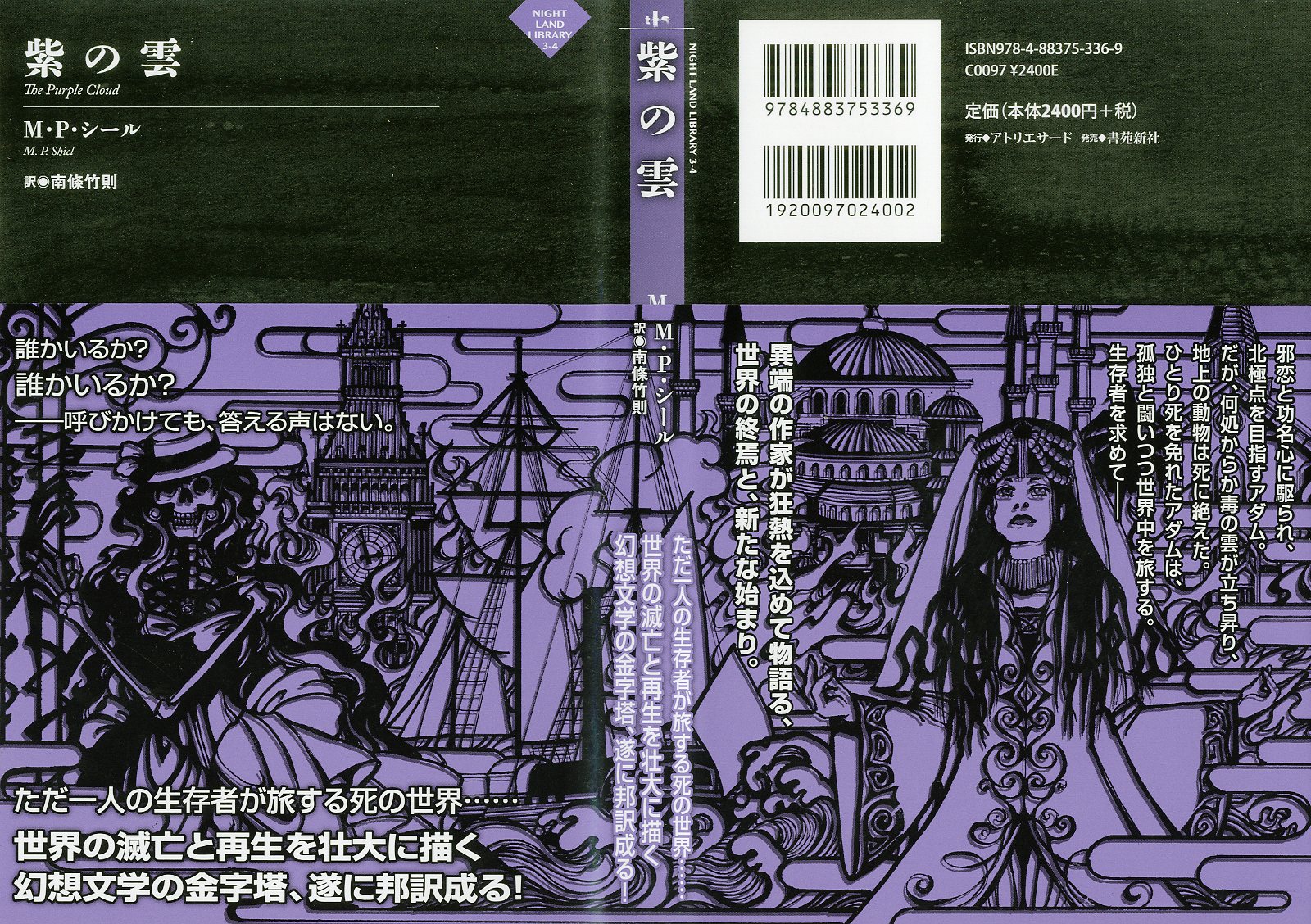

Shiel 2018 (1901)M・P・シール M. P. Shiel This is, of course, a translation of what over the past century has become Shiel's best known and most widely read and translated novel -- The Purple Cloud (see above). The translator, Nanjō Takenori (南條竹則 b1958), has dubbed a number of British and American novels into Japanese. Most, like The Purple Cloud, have been works of fantasy. He is himself a writer of fiction, and in 1993, his historical fantasy novel Shusen (酒仙) [Sake immortal] won the Excellence prize (2nd place) in Shinchōsha's 5th Japan Fantasy Novel Award competition in a field of 574 entries. |