Are there buraku "min"?

A week before I bought copies of the two books under review here, I received a complimentary copy of Christopher Harding's Japan Story: In Serach of a Nation 1850 to the Present (2018). The index refers "burakumin (outcasts)" to the following paragraph, which begins about three pages from the end of the main text of the book (Harding 2018: 399-400).

|

Japan's former outcaste communities face a related problem. Once known by names like hinin ('non-people') and eta ('full of filth'), they are referred to in the modern era as burakumin, after the word for the hamlets (buraku) in which they had lived. But many in an estimated population of around 1.2 million do not want to be referred to as anything at all. Their minority status is based not on ethnicity or on a history of which they were proud, but on stigmatization stemming from their work in professions once regarded as unclean. The solution, said some, is for the concept and category of burakumin to cease to exist. By the early 2000s, some in the Buraku rights movement regarded this as having been achieved: decades of government 'assimilation' ('dōwa') spending on homes, schools and other facilities in burakumin neighborhoods, alongside compensatory education for Buraku children and social education for the general population, aimed at tackling old stigmas, has resulted in few Japanese thinking about the issue any longer. But in 2016 along came a reminder for rights activists of how precarious a position it was to have to rely on others to alter or forget their prejudices: a new law had to be passed, responding to new forms of discrimination, including the moving online of long-running attempts to locate the postal addresses of burakumin communities in order to vet potential employees or marriage partners.

|

While the index states "burkumin (outcasts)" the text italicizes burakumin as the "modern era" name of what are characterized as "former outcastes". This sort of confusion is common in writing about a population that does not really exist except as a figment of imagination, in the minds of (1) people who would discriminate against descendants of "former outcastes" for personal reasons, and (2) people who need to keep the imaginary "minority status" alive for political or academic or journalistic reasons.

2003 appraisal of "buraku issue"

In my preface to Alastair McLauchlan's Prejudice and Discrimination in Japan: The Buraku Issue (2003), I summarized the current state of the called "buraku issue" (buraku mondai 部落問題) as follows.

|

What exists today are:

(1) lingering prejudice and discrimination on the part of some people against the residents and former residents of neighborhoods still associated with pre-1871 outcaste settlements, and ambivalence as to whether such associations should be kept alive through identity politics.

(2) vestiges of social problems, slowly resolving but still endemic to some of these neighborhoods, the accumulated effects of many generations of degrading experiences, poverty, and hopelessness;

(3) conflict between advocacy organizations, some of which have used heavy-handed tactics and demanded radical measures to eliminate prejudice and discrimination, thus ideologically dividing the affected communities and alienating the general public;

(4) envy and jealousy on the part of neighborhoods that have not benefited from the sort of improvements made possible by the special funding sometimes granted communities like Buraku-X;

(5) a national government that, in the absence of a clear political mandate from the elected representatives of prefectural and municipal polities, regards the affairs of Buraku-X and its cousins as primarily the responsibility of local governments, and wishes to avoid legislation that would risk the formation of a permanent class of victims within the national population; and

(6) academics, journalists, and publishers who -- perhaps reflecting the attitudes of a general population that is largely uninformed and apathetic about problems of prejudice and discrimination that seem historically or geographically remote -- are apt to remain silent rather than risk the ire of pressure organizations that have earned a reputation for intolerance of criticism and free speech.

|

This is pretty much how the "buraku issue" stands today, 15 years later. I see only three subsequent developments as remarkable.

- The Dōwa Countermeasure Projects Special Measures Law (Dōwa taisaku jigyō tokubetsu hō 同和対策事業特別措置法) or "Special Measures Law" (Tokubetsu sōchi hō 特別装置法), which provided for improvements in designated "dōwa areas" (dōwa chiiki (同和地域), came into effect in 1969 and expired in 2002. "Dōwa" -- meaning "together in harmony" -- was the national government's appelation for so-called "buraku" that, in the eyes of local governments, needed better infrastructure to raise their standards of living to a par with those of surrounding neighborhoods. The object was to make the designated areas economically inconspicuous so as to be able to regard them as integrated with their neighbors. Improvement projects were politically and fiscally mediated by established BLL offices. On account of its role in fascilitating SML-funded projects, BLL, which was closely linked with the Japan Social Party, became more deeply entrenched in local affairs, At the same time, BLL became more dependent on the project as a way to maintain its influence. BLL's arch rival Zenkairen, which was affiliated with the Japanese Communist Party, had opposed the SML since its proposal in 1965. While BLL and JSP stressed the need for special treatment of so-called buraku, Zenkairen and JCP opposed in principle the special treatment of buraku, and supported only programs intended for all impoverished neighborhoods. So while BLL lamented the termination of SML, Zenkairen celebrated the end of special treatment. Scholars who shared Zenkairen's view of the "buraku problem" argued that "buraku discrimination" had become a problem of the past and declared an "end to buraku history". The small risk of encountering discrimination that still existed could best be reduced by liberating everyone from the very notion of "buraku". And in 2004, Zenkairen eliminated "buraku kaihō"" from its organizational name and became the Zenkoku Chiiki Jinken Und?? S??reng?? (全国地域人権運動総連合) or "National Confederation of Local Human Rights Movements" though it gives its English name as "The National Confederation of Human Rights Movements in Communities". It's briefer name is now or Zenjinren. As a general "human rights" organization, it still views social issues from communist point of view. But what it used to call the “buraku problem” it now calls a “Kaid? problem”.Zenkairen eliminated "buraku kaih??" from its organizational name and became Zenjinren -- a purely, and generally, "human rights" organization.

JCP now calls "ky?? d??wa chiku" (旧同和地区) or "former d??wa areas", and Zenjinrin maintains such areas now need only to be liberated from BLL's domination -- which, in fact, has been taking place.

- Scandals involving an Osaka municipal official who also wore the hat of a Buraku Liberation League (Buraku Kaiho Dōmei 部落解放同盟) leader, accused of malfeasance The actions taken i n 2007 were said to have been sparked by a scandal i nvolvi ng a municipal official of Osaka City who had abused his pri vileges as a local BLL leader i n applyi ng for and receivi ng community fundi ng, rather than by the resolution of the burakuissue.His act was advertised and discussed excessively in national media just before the decision to make the changes was made.

-

The term "burakumin" is problematic for several reasons.

- Use of "burakumin" to minoritize people

"Burakumin" has become more widely used and misused by people who claim, especially in pulibications about Japan in langauges other than Japanese, that "burakumin" are a "minority group" in Japan.

- "Burakumin" is rarely used in Japanese because, in principle, such people do not exist as a legal cohort, nor are they generally constructed as a social minority. Most buraku liberation movement activists prefer to speak of buraku localities and buraku residents as objects of residential discrimination, in the spirit of claiming that all present and former buraku residents -- regardless of their lineal descent or even nationality -- are subject to verbal and other forms of abuse by the few people who persist in negatively characterizing anyone associated with a so-called buraku.

- Use of "burakumin" to historicize subcaste ("outcaste") statuses

"Burakumin" -- a term invented within the past century or so to label the "peopl" (min 民) of so-called "buraku" (部落) -- has been used ahistorically to describe the people who, in the past were, were ascribed subcaste statuses like "eta" (エタ 穢多) or "hinin" (非人), which were legally abolished in 1871.

McLaughlan has more recently made this statement (McLaughlan 2009 (page 1).

Although the Japanese word buraku literally means a hamlet or small village, in many parts of Japan, especially southern Honshu's Kansai, Hiroshima and Hyogo regions, the term has a connotation akin to our own word ghetto. Furthermore, the word burakumin (lit. buraku people) is pejoratively applied to denigrate the residents of buraku villages.

"Buraku" has been widely used everywhere in Japan, until fairly recently, to refer to either a small village or hamlet, or to an enclaved neighborhood within a town or city. Only recently, and mainly on account of political activism on the part of the so-called "buraku liberation" organizations, has it become a "pronoun" for a neighborhood or settlement of people associated -- rightly or wrongly, with or without their consent -- with historical subcaste ("outcaste") settlements.

"Burakumin" would be a "pejorative" only if someone was to use the word contemptuously to label another person. It is widely used in English as though it were the "correct" name of an alleged "minority group". Some buraku liberation activists -- but not many -- have used the term to label people they view as actual or virtual heirs of the label, again with or without the permission of those they would label. However, even when spoken with good intentions by an activist, or journalist or scholar, who felt justified in describing a group or individual this way, the label would be unwelcome to those for whom it was intended, who do not wish to be called "burakumin" if anything. In fact, it appears that the vast majority of the people who are alleged to be "burakumin" appear to dislike any form of exceptionalization as a minority, verbal or otherwise, presumably because they don't wish to "exist" other than as ordinary people.

The significance of "-min"

Practically all writing in English about "minorities" in Japan uses "burakumin" as the name of a "group" or "community" in Japan composed of people who have an "identity" related to a shared history of caste or caste-like discrimination. These broad allegations are false in several respects. This writer himself was educated in the "school" of social sciences -- specifically pyschological anthropology -- at the University of California at Berkeley, under the mentorship of George De Vos, one of the primary archietects of this view, and was later acquainted with his collaborator and co-author Hiroshi Wagatsuma. My own contemporary publications with De Vos reflected this view, which I held for several years after leaving De Vos's academic nest and settling in Japan. I met a number of Japanese sociologists and anthropologists who, for various reasons, shared much of what had become "conventional wisdom". And, in Japan, I witnessed how "buraku liberation movement" activists, including some scholars, attempted to explain and otherwise deal with what was generally called the "buraku mondai" (部落問題) -- the "buraku problem" in the sense of any "issue" or "question" which required at least "understanding" if not also some kind of "solution" or "resolution" in the form of which or "buraku issue" -- about the social history of so-called "burakumin" The "min" (民) of "hisabetsu burakumin" (被差別部落民) refers to "person" or "people" in a much more "clannish" or "communal" sense than "jin" (人) -- very generally speaking. The use of "min" stems from older late 19th century terms like "heimin" (平民) meaning an "ordinary person" or "commoner" as a formal legal status. Japan's 1871 household registration law referred to "people" (jinmin 人民 person people), "nationals" (kokumin 国民 nation people), and "subjects" (shinmin 臣民 subject people). The 1890 Constitution referred to "subjects" and the 1899 Nationality Law and related laws referred to "nationals".

"Jinmin" came to be used in as a generic term for the "people" of any country, collectively, regardless of the terms used in a country's domestic status laws to refer to people individually. While "kokumin" (国民) may be used to refer to "nationals" collectively or to an individual "national" as a member of the demographic "nation" defined by possession of nationality (kokuseki 国籍), "jinmin" is used in Japan to refer to the collectivities of people affiliated with states in international contexts -- but not to the "people of Japan", who are called "Nihon kokumin" (日本国民).

Also in the late 19th century, "min" was used in translations of terms like "folk" (minzoku 民俗) and "volk" or "ethnos" or "nation" (minzoku 民族). By the time the "buraku liberation movement" began in 1922 -- with the (now infamous) "Fellow tokushu burakumin throughout the country, unite!" manifesto -- "min" had acquired a distinctly proletarian flavor, which favored its use continued use among buraku liberationists needed to "label" the people it claimed needed to be liberated from discrimination. In the meantime, East Asian socialists and communists adopted the term 人民 (J. jinmin, C. rénmín, K. inmin) to refer to the "people" as a proletariat liberated from the state, or from the state contrived as a "nation". The "state" or "nation" contrived as a state are supposed to have withered away, leaving the "people" as an entity unto themselves -- hence PRC and DPRK refer to their state nationality holders as "citizens" (公民 J. kōmin, C. gōngmín, K. kongmin) rather than "nationals" (国民 J. kokumin, C. guómín, K. kungmin).

Japan does not define "citizens" as such. People who possess Japan's nationality (kokuseki 国籍) are "kokumin" (国民), meaning "affiliates (民)" of the "country" (国)" or state as a civic (non-ethnic) nation. Only people who possess Japan's nationality are potentially "citizens" of Japan with Constitutional rights of suffrage and other treatments accorded only to "nationals". Japan does not speak of its nationals as either "kōmin" (公民) or "shimin" (市民).

The term "shimin" (市民) is generically used in Japan to conflate all municipal (and by extension prefectural) affiliates, meaning any legal resident of a municipality (and by extension a prefecture) -- regardless of nationality. In other words, only "Japanese" (people who possess Japan's civic nationality) are "nationals", but all legal residents of Japan are "citizens" for municipal and prefectural purposes.

All formal legal terms in Japan for local municipal (ward, city, town, village) residents use the suffix "min" (民) or "affiliate" -- "kumin" (区民), "shimin" (市民), "chōmin" (町民), "sonmin" (村民) -- collectively "kushichōson-min" (区市町村民). Such municipal "affiliates" (citizens) are also, by virtue of their municipal affiliation, "affiliates" (min 民) of the prefectures having jurisdiction over the local entity -- "tomin" (都民) for Tokyo prefecture, "dōmin" (道民) for Hokkaido prefecture, "fumin" (府民) for Kyōto and Ōsaka prefectures, and "kenmin" (県民) for other prefectures -- collectively "todōfuken-min" (都道府県民).

The suffix "jin" (人) is more broadly used in a variey of contexts, some of which "racialize" the usage. For example, "Okinawa kenmin" (沖縄県民) refers to any legal resident of Okinawa, but writers who racialize people they regard as somehow "ethnic" Okinawans may call them "Okinawajin" (沖縄人). Some writers similarly racialize residents of so-called "discriminated buraku"? The This is the case with "buraku" residents as well. Some "Buraku liberationists" avoid speaking of "burakumin" but prefer "buraku jūmin" or "buraku because they feel that "buraku discrimination" is something which affects all it racializes individuals are not supposed to exist rd "citizen" (公民) -- hence its use in the formal names of the People's Republic of China and the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (sic = Chosen), which do not speak of their legal affiliates as "nationals" in reference to the "proletariate" as also has proletarian nuances, which favored the continued use of "kokumin" to designate the "people of Japan" as "nationals" ome people speak of "burakujin" (部落人) when racializing "buraku people" as a specific "type" of human -- in the manner of racialized "Japanese" (Nihonjin 日本人) or racialized "Okinawans" (Okinawajin 沖縄人) or racialized "Chosenese" (Chōsenjin 朝鮮人). In Japan, however, "min" generally implies a formal legal status as an "affiliate" of an entity -- of a country, nation, or state (kokumin 国民), or of a municipality (kushichōsonmin 区市町村民) and prefecture (todōfuken-min 都道府県民). In Japan, only people who possess Japan's nationality (kokuseki 国籍) are "nationals" (citizens) of Japan, but all people who legally reside in a municipality of Japan are "affiliates" (citizens) of the municipality and the prefecture , , when used, has the feeling of an individual, using "min" (民) much like it is used to imply an "affiliate" of a politically defined legal entity, such as "kokumin" (国民) for "national" meaning a person affiliated with a country or nation (kuni 国) or state (kokka 国家) on account of possessing its "nationality" (kokuseki 国籍). The term is also used to denote legal affiliation with a municipality (kushichōson-min 区市町村民) or prefecture (todōfuken-min 都道府県民). So-called "buraku" are neighborhoods, settlements, or communities within municipal entities but "exist" only as objects of private political activism. The term "min" is used in the sense of "tami" (民) areas but have no formal in a sense reminiscent of as one talks about "people of a country" (kokumin 国民) or other legal entity -- using "min" (民) in the sense of "affiliates". rather than "jin" (人) in -- i.e., people as "affiliates as "affiliates" a municipality" (ku-shi-chō-son-min 口s町村民nationals" (kokumin 国民)

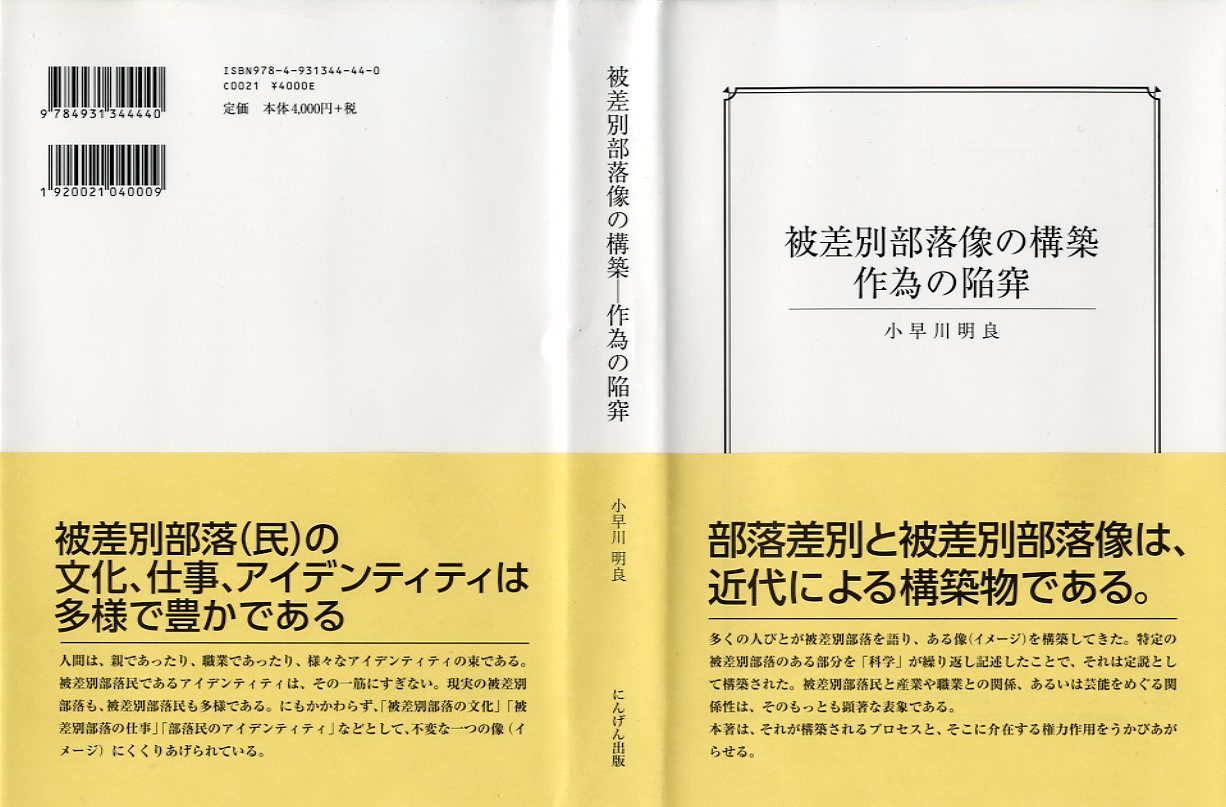

Jacket and obi of Kobayakawa Akira's The constsruction of discriminated images, 2017

Jacket and obi of Kobayakawa Akira's The constsruction of discriminated images, 2017

Yosha Bunko scan

|

Kobayakawa 2017

小早川明良

被差別部落像の構築:作為の陥穽

東京:にんげん出版、2017年12月15日

330ページ、単行本

Kobayakawa Akira

Hisabetsu buraku zō zō no kōchiku: Sakui no kansei

[ The construction of discriminated buraku images ]

[ The pitfalls of contrivance ]

Tokyo: Ningen Shuppan

15 December 2017 1st edition 1st printing published

330 pages, hardcover

Title

The author represents this book in English as Construction of Buraku Imagery: Gimmick of Feasances, Tokyo: Ningen Publishing, 2017. This does not quite capture the Japanese title metaphors, which clearly qualify the so-called "buraku" (部落) as entities that "receive discrimination" (hisabetsu 被差別) hence are "discriminated (against) buraku". The constructed images are not "gimmicks of feasances" but "traps" or "pits" (穽) that one "falls into" (陥) as a result of the "falsehoods" (為) that are "created" (作) by the "construction" (構築) of the "images" (像).

Obi blurbs

The front of the obi very clearly states the books general conclusions -- or rather the viewpoint that the author has attempted to collaborate through his research and writing. The transcriptions, translations, and highlighting and comments are mine.

Front of obi

|

|

部落差別と被差別部落像は、

近代による構築物である。

多くの人びとが被差別部落を語り、ある像(イメージ)を構築してきた。特定の被差別部落のある部分を「科学」が繰り返し記述したことで、それは定説として構築された。被差別部落民と産業や職業との関係、あるいは芸能をめぐる関係性は、そのもっとも顕著な表象である。

本著は、それが構築されるプロセスと、そこに介在する権力作用をうかびあがらせる。

|

Buraku discrimination and discriminated buraku images,

are constructions of recent era.

Many people have talked about discriminated buraku, and come to construct certain images. Through the "science" having repeatedly described certain parts of specific discriminated buraku, they [these images] have been constructed as established views. Relations of discriminated burakumin with industries and occupations, and relatedness around [involving] entertainment, are the most prominent representations,

This book will raise to the surface [reveal] the processes by which they [these representations] are constructed, and the authority actions that intervene there [are involved there in].

|

Bracketed "science"

Kobayakawa takes issue with the manner in which scholars have created images of discriminated buraku in the name of "science" -- treating their observations of as "scientific" and arriving at conclusions that are taken to be "truthful" because they appear to follow from "objective" analyses of "factual" data.

|

Back of obi

|

|

被差別部落(民)の

文化、仕事、アイデンティティは

多様で豊かである

人間は、親であったり、職業であったり、様々なアイデンティティの束である。被差別部落民であるアイデンティティは、その一筋にすぎない。現実の被差別部落も、被差別部落民も多様である。にもかかわらず、「被差別部落の文化」「被差別部落の仕事」「部落民のアイデンティティ」などとして、不変な一つの像(イメージ)にくくりあげられている。

|

Cultures, work, and identities

of discriminated buraku (min)

are diverse and abundant

Humans are parents,occupations, bundles of various identities, The identities of discriminated burakumin are merely single lines of those. Actual discriminated buraku, and discriminated burakumin too are diverse. Nonetheless, [these diverse identities] are bound together into an unchanging single image, as "discriminated buraku culture", "discriminated buraku work", "burakumin identity" et cetera.

|

Parenthetic (min)

Kobayakawa rarely uses parentheses to specify both "hisabetsu buraku" and "hisabetsu burakumin". He generally specifies one or the other, or both in series. Moreover, he talks far more about "discriminated buraku" than about "discriminated burakumin". He sometimes speaks of buraku unqualified by "discriminated" but rarely speaks of burakumin without this qualification.

|

|

Top

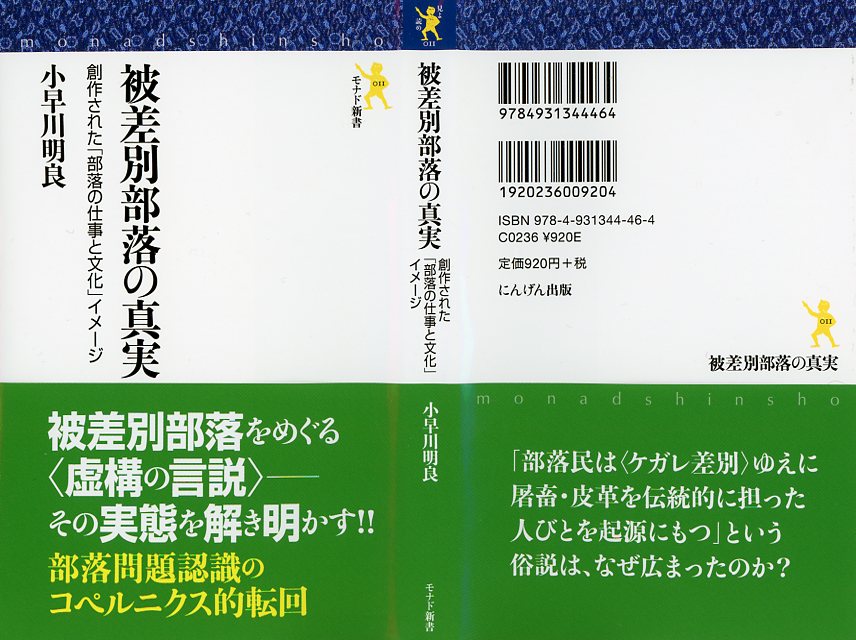

Jacket and obi of Kobayakawa Akira's The truth about discriminated buraku, 2018

Jacket and obi of Kobayakawa Akira's The truth about discriminated buraku, 2018

Yosha Bunko scan

|

Kobayakawa 2018

Where have all the "burakumin" gone

and the "trap of identity

小早川明良

被差別部落の真実

(創作された「部落の仕事と文化」イメージ)

東京:にんげん出版、2018年9月18日

288ページ、モナド新書11

Kobayakawa Akira

Hisabetsu buraku no shinjitsu

(Sōsaku sareta "Buraku no shigoto to bunka" imeeji)

[ The truth about discriminated buraku ]

[ (The created "Buraku work and culture" images) ]

Tokyo: Ningen Shuppan [Ni

18 September 2018 1st edition 1st printing published

288 pages, softcover, Monado Shinsho 11

ISTAD's English pages give the title as The Truth of Buraku, Constructed Imagery about Occupations and Cultures in Buraku, Tokyo: Ningen Publishing, 2017. This English title fails to reflect the style of the Japanese title and lacks the "discriminated" qualification that is indispensible in Japanese writing on the so-called "buraku issue".

Obi blurbs

The front of the obi very clearly states the books general conclusions -- or rather the viewpoint that the author has attempted to collaborate through his research and writing. The transcriptions, translations, and highlighting and comments are mine.

Front of obi

|

|

被差別部落をめぐる<虚構の言説>

その実態を解き明かす!!

部落問題認識の

コペルニクス的転回

|

Exposes the actual conditions of the

"fictional discourse" about discriminated buraku!!

A Copernican revolution of

buraku issue recognition

|

Bracketed "science"

Kobayakawa takes issue with the manner in which scholars have created images of discriminated buraku in the name of "science" -- treating their observations of as "scientific" and arriving at conclusions that are taken to be "truthful" because they appear to follow from "objective" analyses of "factual" data.

|

Back of obi

|

|

「部落民は<ケガレ差別>ゆえに

屠畜・皮革を伝統的に担った

人びとを起源にもつ」という

俗説は、なぜ広まったのか?

|

Why did the folkview spread that "burakumin,

because of 'pollution discrimination',

have in their origins in people who

traditionally slaughtered livestock and worked with hides"?

|

Parenthetic (min)

Kobayakawa rarely uses parentheses to specify both "hisabetsu buraku" and "hisabetsu burakumin". He generally specifies one or the other, or both in series. Moreover, he talks far more about "discriminated buraku" than about "discriminated burakumin". He sometimes speaks of buraku unqualified by "discriminated" but rarely speaks of burakumin without this qualification.

|

|

Top

Kobayakawa Akira

Kobayakawa Akira (小早川明良) is a retired business man who has turned his lifelong interest and involvement in the so-called "buraku problem" (buraku mondai 部落問題) into a post-retirement vocation. He is a member of the Institute of Social Theory and Dynamics (ISTAD), an NPO (Tokutei Hi-eiri Katsudō Hōjin 特定非営利活動法人 Special non-profit activity judicial person) known in Japanese as "Shakai Riron·Dōtai Kenkyū" (社会理論・動態研究所). ISTAD is based in Hiroshima city, and it's members are heavily invested in critical sociological studies of minorities and underclasses.

The Japanese section of ISTAD introduces 小早川明良 (Kobayakawa Akira) as an ISTAD researcher and board member who specializes in , of directors who specializes in "Studies of the buraku problem (Buraku mondai no kenkyō 部落問題の研究). The English section introduces Akira Kobayakawa as only a member of ISTAD and states that he specializes in "Research of Buraku problem in Japan".

Kobayakawa describes his activities as follows in Japanese and English.

|

被差別部落と日本の近代(化)の関係を中心に研究している。

それは、大きくわけて二つの分野になる。第1は、軍事都市に形成された近代被差別部落と職業・生活などにフォーカスした研究である。

第2は、市民が抱く被差別部落と被差別部落民に対する否定的なイメージや、マスター・ナラティブの構築にかんする批判的研究である。

|

I study relationships of late modernity and the Buraku [sic = discriminated buraku]. These are broadly two. The first is a study, based on field work, of new [sic = recent era] Buraku constructed in military cities. The second is a critical study against [sic = concerning] negative imagery of Buraku and Burakumin held by commoners, and the construction of the master narrative.

|

Top

Institute of Social Theory and Dynamics (ISTAD)

Facebook

https://www.facebook.com/pg/istdjapan/posts/

Top

Kobayakawa's "The Buraku Issue" website

In addition, Kobayakawa has a copy-protected English website called The Buraku Issue on which he has published English versions of a number of his articles, mainly excerpts from his writing in Japanese. The website includes publicity for his publications under The Buraku Issue -- Books, which includes an English version the foreword to his 2017 book.

Top

Kobayakawa Akira's Kaken projects

科研費

|

KAKENHI 研究課題をさがす

科学研究費助成事業データベース

科学研究費助成事業データベースは、文部科学省および日本学術振興会が交付する科学研究費助成事業により行われた研究の当初採択時のデータ(採択課題)、研究成果の概要(研究実施状況報告書、研究実績報告書、研究成果報告書概要)、研究成果報告書及び自己評価報告書を収録したデータベースです。科学研究費助成事業は全ての学問領域にわたって幅広く交付されていますので、本データベースにより、我が国における全分野の最新の研究情報について検索することができます。

|

KAKEN Grants

Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research

Database of Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKEN) is a public database which includes information on adopted projects, assessment, and research achievements from the Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) Program. This system is hosted by the National Institute of Informatics (NII)in cooperation with MEXT and JSPS.

|

Kaken projects

2013-2015 Kaken project

部落問題についての「科学的」言説批判

Buraku mondai ni tsuite no "kagaku-teki" gensetsu hihan

[ Crtique of "scientific" discourse about buraku issue ]

|

| 研究代表者 |

小早川 明良 |

| 研究期間 (年度) |

2013 -- 2015 |

| 研究種目 |

基盤研究(C) |

| 研究分野 |

社会学 |

| 研究機関 |

特定非営利活動法人社会理論・動態研究所 |

2017-2019 Kaken project

近代被差別部落の形成と同意の構造:軍都と部落問題

Kindai hisabetsu buraku no keisei to dōi no kōzō:

Guntai to buraku mondai

[ Structure of formation and acceptance of recent-era discriminated buraku:

Military cities and the buraku issue ]

|

| 研究代表者 |

小早川 明良 |

| 研究期間 (年度) |

2017 -- 2019 |

| 研究種目 |

挑戦的研究(萌芽) |

| 研究分野 |

社会学およびその関連分野 |

| 研究機関 |

特定非営利活動法人社会理論・動態研究所 |

Top

2013-2015 project

https://kaken.nii.ac.jp/ja/grant/KAKENHI-PROJECT-25380733/

2013-2015 Kaken project

部落問題についての「科学的」言説批判 |

| 研究課題/領域番号 |

25380733 |

| 研究種目 |

基盤研究(C) |

| 配分区分 |

基金 |

| 応募区分 |

一般 |

| 研究分野 |

社会学 |

| 研究機関 |

特定非営利活動法人社会理論・動態研究所 |

| 研究代表者 |

小早川 明良 特定非営利活動法人社会理論・動態研究所, その他部局, 研究員 (10601841) |

| 研究分担者 |

藤田 成俊 特定非営利法人社会理論・動態研究所, 研究員 (20605026)

伊藤 泰郎 広島国際学院大学, 情報文化部, 教授 (80281765) |

| 研究期間 (年度) |

2013-04-01 -- 2016-03-31 |

| 研究課題ステータス |

完了(2015年度) |

| 配分額 *注記 |

3,640千円 (直接経費 : 2,800千円、間接経費 : 840千円)

2015年度 : 650千円 (直接経費 : 500千円、間接経費 : 150千円)

2014年度 : 780千円 (直接経費 : 600千円、間接経費 : 180千円)

2013年度 : 2,210千円 (直接経費 : 1,700千円、間接経費 : 510千円) |

| キーワード |

小数点在部落 / 屠畜 / 竹製品 / 製革 / 製靴 / 概念の構築 / 部落問題の科学的認識 / 部落産業 / 少数点在型部落 / 観念の構築 / 部落問題の「科学的」研究 / 部落弾業 / 竹細工 / 製靴産業 / 皮革産業 / 広島県 / 観念の構成 |

| 研究成果の概要 |

一般的に広く存在する被差別部落が屠畜・精肉、製靴などの皮革産業、竹細工と深く関係しているという考え方は、たんなるステレオタイプに過ぎない。その考え方が国民の間に形成されたことは、「科学的研究」の責任の一端がある。明治の初めから、これらの産業・職業の主要な位置を占めたのは、非被差別部落の経営者であり、労働者であった。現在では、被差別部落の人びとは、その立場は弱くてもそれぞれの地域の産業構造に組み込まれ、生産の一翼を担っている。

被差別部落にあって、非被差別部落にない産業・職業は一切存在しない。これが研究の結果である。 |

Top

Kaken project 2017-2019

https://kaken.nii.ac.jp/ja/grant/KAKENHI-PROJECT-17K18601/

2017-2019 Kaken project

近代被差別部落の形成と同意の構造 軍都と部落問題

|

| 研究課題/領域番号 |

17K18601 |

| 研究種目 |

挑戦的研究(萌芽) |

| 配分区分 |

基金 |

| 研究分野 |

社会学およびその関連分野 |

| 研究機関 |

特定非営利活動法人社会理論・動態研究所 |

| 研究代表者 |

小早川 明良 特定非営利活動法人社会理論・動態研究所, 研究部, 研究員 (10601841) |

| 研究分担者 |

青木 秀男 特定非営利活動法人社会理論・動態研究所, 研究部, 研究員 (50079266) |

| 研究期間 (年度) |

2017-06-30 -- 2020-03-31 |

| 研究課題ステータス |

交付(2017年度) |

| 配分額 *注記 |

6,240千円 (直接経費 : 4,800千円、間接経費 : 1,440千円)

2019年度 : 2,080千円 (直接経費 : 1,600千円、間接経費 : 480千円)

2018年度 : 1,950千円 (直接経費 : 1,500千円、間接経費 : 450千円)

2017年度 : 2,210千円 (直接経費 : 1,700千円、間接経費 : 510千円) |

| キーワード |

社会学 / 部落問題 / 差別のまなざし / 被差別部落の形成 / 被差別部落の消滅 / 軍都形成 / 強制と同意 |

| 研究実績の概要 |

計画書の予定通り、まず舞鶴、呉、広島の各市にかんする基本的な資料調査を行った。舞鶴以外の予定していた施設の資料も閲覧した。施設の学芸員からも助言を得た。被差別部落の方々の協力もありフィールドワークも行えた。その結果、特に呉市においては、全く新しい発見があった。海軍鎮守府造営時以降、市内すべての被差別部落が大きく変容し続けた。現在、被差別部落A2町に接するA1町とA3町は、行政の認識でも市民の認識でも被差別部落とされない。ゆえに国の同和対策事業予算執行の対象外であった。しかし、戦前資料では、被差別部落とみなされたこの二つの町には、部落改善予算が執行されていた。一般市民もメディアも被差別部落として認識していた。申請者は、A2地区のみが被差別部落として扱われるようになるのは、1950年半ば以降と推測している。海軍鎮守府造営以前から存在した1カ所の被差別部落が、鎮守府用地確保のため立ち退きになったが、申請者は、不明であった移転先を突き止めた。移転は、4カ所に分散し、うち3カ所は1945年までに消滅した。移転しなかった他の被差別部落が2カ所の消滅と、その理由も確認した。これらの成果は、被差別部落が近代の構築物であることを実証する重要なエビデンスとなる。

広島市F町については、毎月のF町研究会に出席した。被差別部落と非被差別部落の境界の変化、人口の急増、職業の特徴が明らかになってきた。

旧舞鶴市では、全6カ所の内4カ所の被差別部落が舞鶴海軍鎮守府造営の過程で形成されたこと確認した。先行研究では、鳥取県から工事に動員された鳥取県の被差別部落から定住した人たちとされた。しかし米騒動の検挙者のデータからはより広範囲から移住者が確認できる。呉鎮守府の工事が終り、職を失った労働者の移住もあった。近代形成の被差別部落について、R.P.ドーア氏が残した手書きノートを入手した。 |

| 現在までの達成度 (区分) |

現在までの達成度 (区分)

2 : おおむね順調に進展している

理由

平成29年度は、1期を呉市、2期を広島市、3期を舞鶴市における調査に均等に時間を配分するよう計画した。研究全体としては、予定以上に成果があった部分、やや遅れた部分、予定通りの部分が混在している。

呉市の調査では、資料的な収穫、先行研究の精読、フィールドワークによる確認が進んだ。その結果、研究実績の概要の項で記した通りの結果を得ることができた。それには、地元被差別部落から複数の研究協力者を得ることができたことが大きく貢献している。そのなかの特に熱心なお一人の都合もあり、またそれに答える意味でも、一定期間、毎日曜日に呉市に出向き、被差別部落調査に傾注することになった。それに伴い、一般の呉市民に対する聞き取りも始まった。これは、本研究への助成金交付申請書研究の目的に記した重要事項である。初年度からこれが可能となったのは思いがけない進捗だった。論文執筆に備えて、入手資料の重要部分から優先的に、入力も実施した。現在、論文の執筆に取りかかっている。すなわち呉市の調査は計画以上に進んでいる。

舞鶴市に対する研究は資料の入手は順調である。現在入手閲覧な資料の多くを確保している。特に、国会図書館、国立公文書館、防衛省防衛研究所への調査は、対象3市のすべてをカバーできている。しかし、上記呉市の調査研究に傾注した結果、資料分析にやや遅延が出ている。また、フィールドワークは、予算交付前に1回3日間しか実施できておらず、これが遅れているとする点である。

広島市については、F町の研究会に参加する機会をえて、認識を新たにすることがあった。地元からの資料提供や情報提供も受けることができた。申請者も、2度研究成果の一端を披瀝した。これはほぼ予定通りの進捗であった。このF町にかんする分野では、予定通りに進んでいる。 |

| 今後の研究の推進方策 |

本研究申請時の計画では、平成30年度は、呉市への調査を優先するとしていたが、それを変更する。そして舞鶴市にたいする調査研究の遅れを取り戻す。フィールドワークを重点的に行い、舞鶴の軍事史、社会史に関する先行研究を精読する。昨年度の調査で、所蔵資料の重要性を再認識したので防衛省防衛研究所を再訪したい。

前年度の先行研究検討では、舞鶴市の近代被差別部落形成を鳥取県の被差別部落からの移住とする先行研究批判の可能性を見つけたので、平成30年度は、その検証に傾注し、全体のディテールを明らかにしたい。このことは、舞鶴市が軍都として発展する過程と被差別部落形成の関係だけではなく、日本全体の近代化過程と被差別部落形成の関係を問う上で重要である。さらに、多様な地域から移住した人たちが、同じ被差別部落民とみなされることにどのように同意をしたのか、という問いに答えることになる。これは、呉市のケースとともに、研究全体を貫くテーマである。そしてそれは、従来の部落問題研究に一石を投じることにもなる。

ところで、舞鶴市関連のデータは、他に比べて少ない。そのため、資料の読み込み、ドーア氏ノートの分析などを行う。そして、「同意の構造」を解明する手がかりをえるため、被差別部落の人々、一般市民へのインタビューに挑戦する。もちろん現在、舞鶴市に鎮守府があった当時のことを知る人はいない。ゆえに、今を生きる当事者にどのように継承されているかを調査する。この分析は、解釈如何でいかようにも判断されるので、慎重な議論を行う。先行研究者によるインビューの記録の読み込みも行い、慎重に検討する。

広島市の調査研究は、予定通り地元のF町研究会を核として行う。発表も予定している。呉市にかんする成果は論文の形にまとめる努力をする。

途中の成果は、毎月の社会理論・動態研究所におけるマイノリティ研究会の場を借りて、議論を提起する。 |

Top

Publications

The two books reviewed here are published by Ningen Shuppan (にんげん出版) [Ningen Publishing], a company run by Kobayashi Kenji (小林健治 b1950), formerly an official of the Buraku Liberation League. See Kobayashi 2011, 2016 on the Censorship page of the Terminology section of the Yosha Bunko's Konketsuji website for details about Kobayashi's word policing activities, first within BLL as a member of its central headquarters, now as an ousted member.

In addition to the two books reviewed here, Kobayakawa Akira has published the following articles, among others, in ISTAD's annual journal Social Theory and Dynamics (STAD), and in local buraku liberation research journals, and on his website.

Kobayakawa 2009

小早川明良

国民を自覚する装置:部落問題研究の新たな枠組みのために

理論と動態

第二号、2009年

ページ73-96

Kobayakawa Akira

Kokumin o jikaku suru sōchi:

Buraku mondai kenkyū no arata-na wakugumi no tame ni

[ A measure to be self-aware of the people (nationals of Japan):

For a new framework of buraku issue studies ]

< The invention of an apparatus on the conception of national consciousness:

For the new paradigm of the Buraku problem studies >

Riron to dōtai

[ Theory and Dynamics ]

Number 2, 2009

Pages 73-96

The English title received with the English abstract (page 38) does not reflect the metaphors of the Japanese title. The translation makes the simple though not quite clear title more complicated and even less comprehensible.

Kobayakawa 2015

小早川明良

差別と生と通俗道徳:闘わなかったある被差別部落民一族の自立

理論と動態

第八号、2015年

ページ20-38

Kobayakawa Akira

Sabetsu to sei to tsūzoku dōtoku:

Tatakawnakatta aru hisabetsu burakumin ichizoku no jiritsu

[ Discrimination and life and common ethics:

The independence of a certain discriminated burakumin clan that didn't fight ]

< Discrimination, Life, and Common Ethics:

The Independence of a Certain Politically Unorganized Family from the Buraku >

Riron to dōtai

[Theory and dynamics]

< Social Theory and Dynamics >

No. 8, 2015

ページ20-38

The English title received with the English abstract (page 38) does not reflect the "discriminated burakumin" label of the Japanese title. Moreover, it interprets "didn't fight (struggle)" as meaning "politically unorganized". And "family" does not quite capture the sense of "ichizoku" (single clan) as a descent group.

Kobayakawa 2015

小早川明良

敗戦直後の部落問題研究批判:丸山眞男を時代診断の手がかりとして

部落解放研究

広島:広島部落解放研究所

2015年1月発行、23号、ページ55-75

Kobayakawa Akira

Haisen chokugo no buraku mondai kenkyū hihan: Maruyama Masao o jidai shindan no tegakari to shite

[Buraku issue studies criticism immediately after lost war: Taking Maruyama Masao as a clue to era diagnosis ]

Buraku kaihō kenkyū

[ Buraku liberation studies ]

Hiroshima: Hiroshima Buraku Kaihō Kenkyūjo

< Hiroshima Buraku Liberation Research Institute >

January 2017, No. 23, pages 55-75

Kobayakawa 2019

小早川明良

欧米人研究者の部落問題研究とオリエンタリズム:アウトカーストと被差別部落

部落解放研究

25号、2019年1月発行、ページ

Kobayakawa Akira

Ōbeijin kenkyūsha no buraku mondai kenkyū to orientarizumu: Autokaasuto to hisabetsu buraku

[ Buraku issue research by Euroamerican researchers and Orientalism: Outcastes and discriminated buraku ]

Buraku kaihō kenkyū

[ Buraku liberation research ]

Hiroshima: Hiroshima Buraku Kaihō Kenkyūjo

< Hiroshima Buraku Liberation Research Institute >

January 2019, No. 25, pages

https://blog.goo.ne.jp/burakukaihouhiroshima

研究紀要およびバックナンバーをご希望の方は、研究所事務局または下記Eメールまでご連絡ください。

ただし2018年5月現在、1号、2号、3号、4号、6号、8号、9号、11号の在庫はありません。ご入要な場合は、個別に閲覧の方途を考えます。

連絡先

722-0041

広島県尾道市防地町24-27

ヒロシマ人権財団内

電話:0848-37-4381

Eメール: hiro_kenkyuu@yahoo.co.jp(事務所)

info@istdjapan.org(研究紀要担当)

印刷所

ノーイン株式会社

岡山市北区富町2丁目5-27

The journal is also known as Hiroshima Buraku Kaihō Kenkyūjo Kiyō (広島部落解放研究所紀要) or "Bulletin of Hiroshima Buraku Liberation Research Institute".

The English titles of the article on ISTAD and study

“A Criticism of Post-Defeat Buraku Studies: Using Maruyama Masao’s Method as Clue for Diagnosis of Modern Times, BURAKU KAIHO KENKYU, Hiroshima Institute of Buraku Liberation Research, no.23, pp.55-75, 2017.

Top

|