Bilingual education

A way to identity

By William Wetherall

San Francisco Examiner

Wednesday, 11 June 1975, page 35

First posted 16 December 2025

Last updated 17 December 2025

Click on images to enlarge Wetherall v. Wright

|

|

Hayakawa joins the fracas

|

|

Wetherall v. Wright

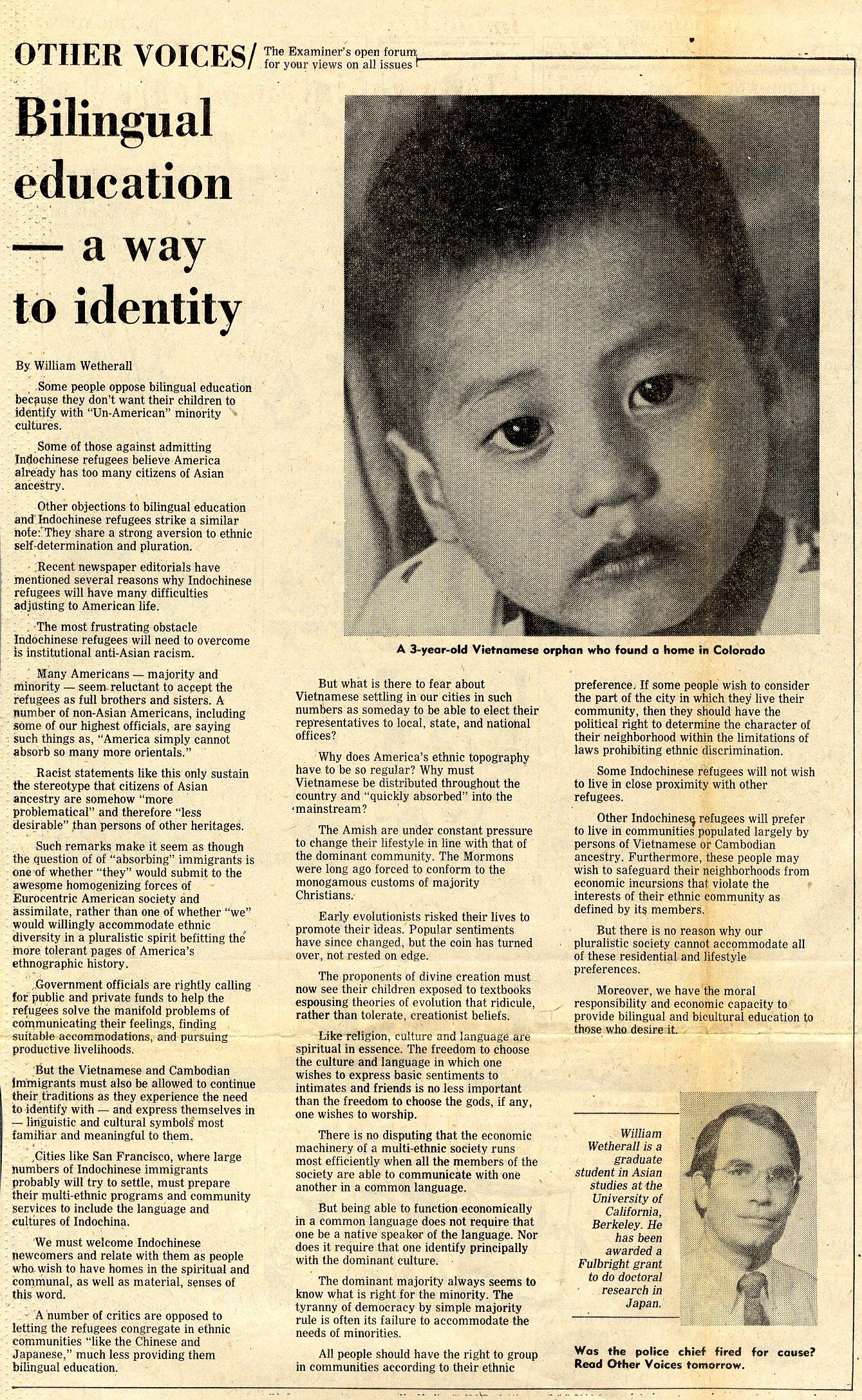

Bilingual education

San Francisco Examiner, 1975

In the spring of 1975, I was completing my course work in a multi-disciplinary PhD program in Asian Studies with an emphasis on Northeast Asia, meaning Japan and Korea -- actually three Koreas -- Kankoku, Chosŭn, and Chōsen. I had put the program together with the endorsement of a committee of 5 faculty members representing 4 departments.

The 3 principle members, who would supervise my dissertation on Following-in-death in Early Japan, were the committee chair, George De Vos (1922-2010) in the Department of Anthropology, and Bill McCullough (1928-1997) and Frank Motofuji (1919-2006) in the Department of Oriental Languages. I started my College of Letters and Science studies as an OL major in the fall of 1967, after transfering from the Department of Electrical Engineering in the College of Engineering. I then migrated to the interdepartmental Group in Asian Studies, with one foot in OL department the other in Antho. The 2 outside examiners, who joined the 3 supervisers in the oral examination that qualified me for candidacy, were Wolfram Eberhard (1909-1989) in the Department of Sociology, and Delmer Brown (1909-2011) in the Department of History.

I had taken most of my specialized course work from De Vos, a psychological anthropologist who specialized in suicide, delinquency, and social discrimination, and McCullough, a classical Japanese literature specialist who had written about marriage and adoption in early Japan using contemporary sources, including literature. De Vos was the inspiration for my dynamic approach to understanding the human condition, and the importance of personality as a mediator of culture. McCullough inspired my scholarship, such as it is. I knew Brown through only one course, a graduate seminar on Japanese history, and it became clear that we didn't share views of history or human behavior. I never took a course from Eberhard -- an "old China hand" who was more an anthropologist than a sociologist. I met him through one of his students, who had written a monograjph on suicide in China, I visited him in his office a number of times, and he was more than happy to share his insights with me.

As busy as I was -- also applying for three doctoral research grants, 2 of which I would receive -- preparing to move to Japan, and managing the apartment building where I lived north of campus -- I somehow found time to read the San Francisco Examiner, carry on a rather heated exchange with one the paper's columnists in its Editor's Mail Box column, and submit the following op-ed the its Other Voices forum.

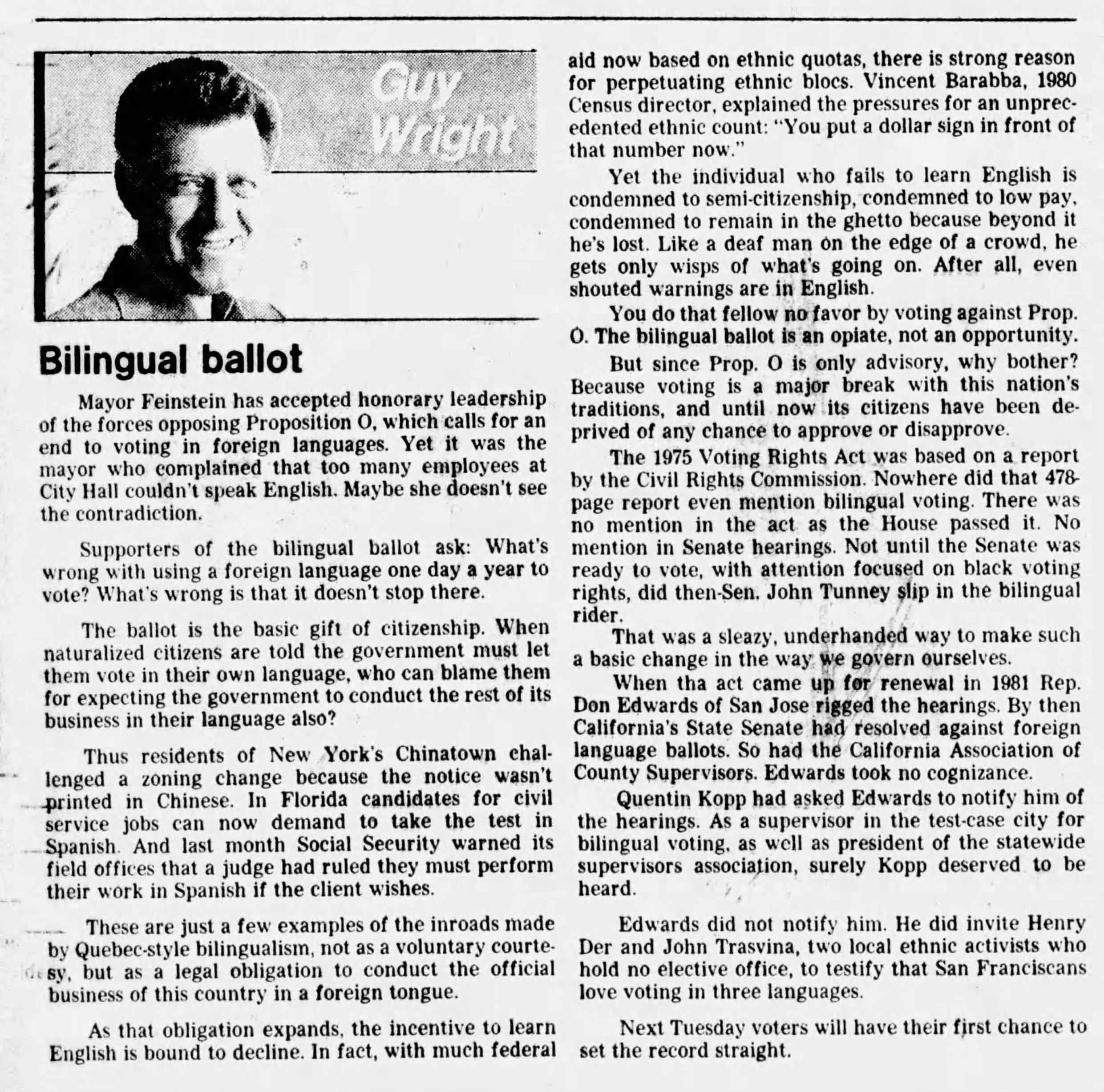

Guy Wright on bilingual education

My sparring partner was Guy Wright (1923-2006), who won 4 bronze stars in as many European campains during World War II, after which he got a degree in journalism through the GI Bill, and went on to become one of San Francisco's better known columnists.

The funny thing is, today yours truly would agree more with Wright than I did in 1975, at the height of my attraction for what I now regard as fashionable rather than thoughtful understandings of history and contemporary social issues.

Wright was staunchly opposed to bilingual education. He went on to become voice for the "Official English" movement. His position is clearly stated in , writing commentary in 1983 that "The individual who fails to learn English is condemned to semi-citizenship, condemned to low pay, condemned to remain in the ghetto".

I am far more radical today, but in ways that run counter to the radicalism of some of the "attitudes" that Wright disliked in my first critique of his

Official English

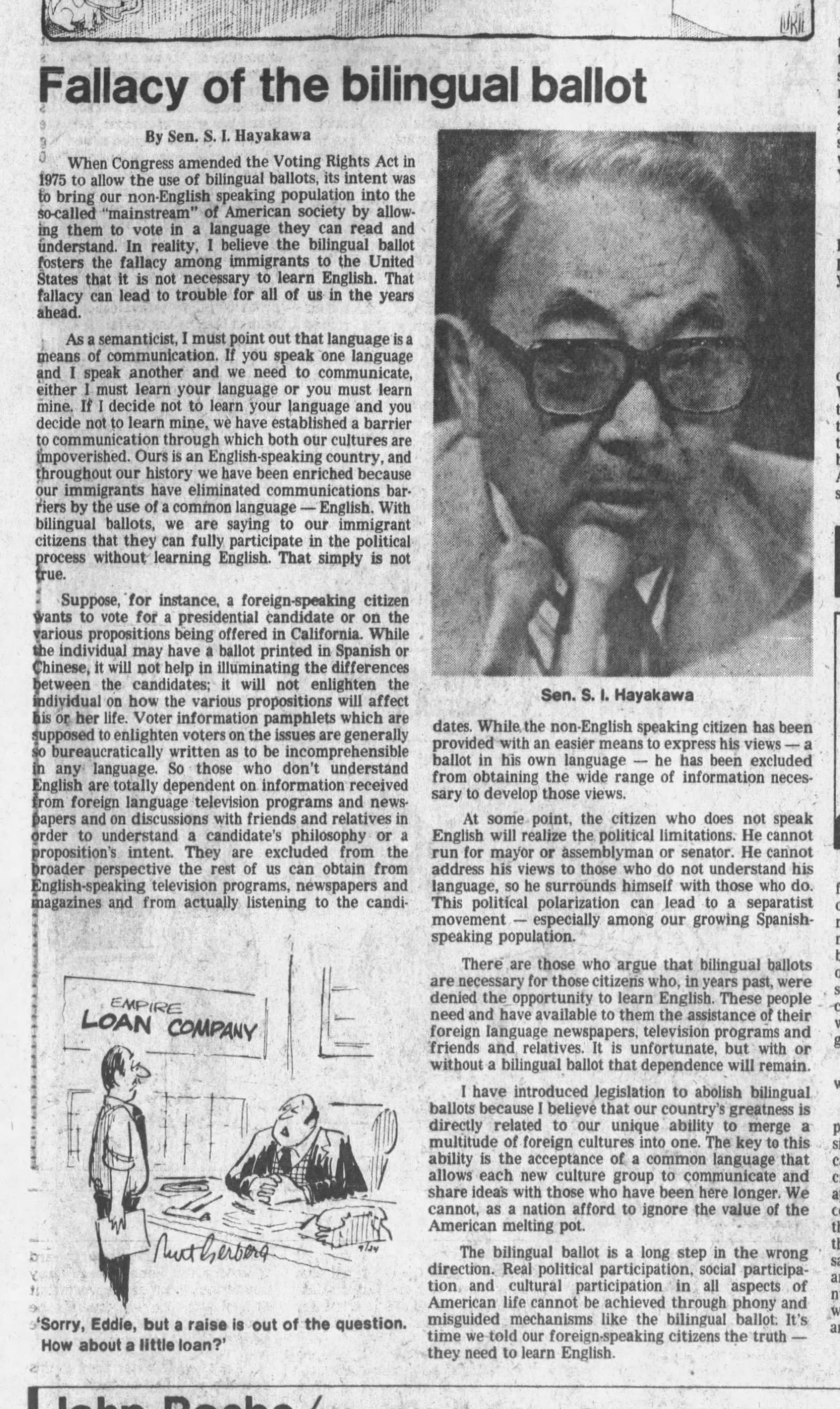

Advocacy for the adoption of English as the de jure official language of the United States goes back a long way. More recently though, in 1983, the linguist Samuel Ichiye Hayakawa, better known as S.I. Hayakawa (1906-1992), spearheaded a movement to congressionally adopt English as the official language of the United States.

Hayakawa was born Victoria in British Columbia, was raised in Canada, and received a BA and an MA in English from Canadian universities. His parents, both from Japan, returned to Japan in 1929, after which Hayakawa migrated to the United States and became a doctoral student at the University of Wisconsin. By 1935 he had received a PhD in English and become a professor of English. His continuous residence in the United States began from 5 March 1937, and he married Margedant Peters, a U of W graduate, on 29 May 1937.

The 1940 census for Chicago shows "Hayakawa Samuel" (33) with his wife "Margedant" (25). He was born in "Canada Japanese" and is "Al" by "Citizenship of the foreign born", and she was born in "Indiana". By "Color or race", he is "Jp" and she is "W". He was a professor and she was a general assistant at a magazine.

A D.S.S. (Department of Selective Service) Form 1 registration card dated 16 October 1940, for "S.I. Hayakawa", gives his wife's name as "Mrs. Margedant Peters Hayakawa". They are residing in Chicago, where he was a professor at the Illinois Institute of Technology. He is racially "Oriental".

In 1941, Hayakawa's most famous book -- Language in Thought and Action -- was published, under its original title, Language in Action: A Guide to Accurate Thinking. The book was a best seller, and it became even more popular from when revised, enlarged, and retitled in 1949, The journalist and free lance writer Alan R. Hayakawa joined the by-line when assisting his father with the 5th and last edition in 1991, the year before his father died.

Language in Thought and Action is still in print. It was partly inspired by the "general semantics" movement started by Alfred Korzybski (1879-1950) with the 1933 publication of Science and Sanity: An Introduction to Non-Aristotelian Systems and General Semantics. Hayakawa's book, as a popularlization of Korzybski's ideas, is considered a foundational text in the history of the study of general semantics.

The general semantics movement continues today. The Institute of General Semantics, founded by Korzybski in Chicago in 1938, is alive and well and has a website. The institute "promotes a scientific approach to understanding human behavior, especially as related to symbol systems and language." Korzybski's followers believe that human nature can be changed for the good, to eliminate wars and other insanities of civilization, by applying his understandings of how to control cognitive, emotional, and behavioral responses through effective use of language and symbols. While general semanticists claim their understandings of human thought and behavior are based on emperical science, they have dogmatic qualities that make the movement more like a save-the-world or self-help philosophy, if not a religion, or even a cult.

My 1966 California Engineer article on Cybernetics and Semantics was partly inspired by Hayakawa's 1941 and 1962 books, and by Korzybski's book and others that inspired Hayakawa.

The 1950 census for Chicago shows "Hayakawa, S.I." (43) with his wife Margedant (35) and sons Alan (3) and Mark (1). He is a "Lecturer, Writer" at university. He was born in Canada, she in Indiana, and his naturalization status is "No", as he is still an ineligible alien. By "Race", he is "Jap", she is "W", and their sons are "Jap".

Hayakawa filed a Petition for Naturalization in Chicago on or about 9 Feburary 1954, and took an oath of allegiance and was issued a certificate of naturalization on 11 November 1954. Alien residents of the United States, regarded as "oriental" by "national origin", became eligible for naturalization after the enactment of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 (Pub. L. 82-414), also known as the McCarran-Walter Act, enacted on 17 June 1952. On the petition, he billed himself as a "Writer & Teacher".

Some people refer to Hayakawa as a "Japanese American" and regard him as a "nisei" or 2nd generation, which usually means a child born outside Japan to "issei" or 1st generation parents who had emigrated from Japan. However, Hayakawa did not fully identify with "Japanese Americans" as a "community". At times he strongly criticized the Japanese American Citizens League. He also disliked being dubbed a "nisei" and opposed the continuation of "nisei" organizations, arguing that "they were no longer necessary and retarded full participation in society" (S.I. Hayakawa, Greg Robinson, Densho Encyclopedia, last updated 27 June 2025 and viewed on 17 December 2025).

From 1955, Hayakawa became a professor of English at San Francisco State College. In 1968, at height of the student movements that disrupted many campuses in the late 1960s, he became president of the college, and gained national fame as a law-and-order hard-liner by physically ripping wires out of a loudspeaker at a student demonostration. He retired from academeia in 1973, begin writing columns and op-eds, and became a politician. he became the president emeritus of the college when it was renamed California State University at San Francisco in 1973.

In 1976, using his reputation as a conservative intellectual activist as a springboard to politics, Hayakawa was elected on a Republican ticket to a 6-year term as a U.S. senator from California, which he served from 1977 to 1983. He then started an organization called "U.S. English", which sought to make the language the tongue of the land.

Hayakawa was not opposed to bilingualism, but considered it a private matter. He saw English as the language of the public sphere -- i.e., the language of citizenship.

Bilingual ballots in California

A federal Voting Rights Act and California state Elections Code determine what languages election materials are to be made available on a county-by-county basis. In Nevada County, where this writer is registered to vote as a U.S. residing overseas, federal law does not mandate languages other than English, but state codes require the county to also provide materials in Spanish. In Los Angeles, at the opposite end of the spectrum, federal law mandates 6 languages other than English, while state codes require 14 other languages (Language Requirements for Election Materials, California Secretary of State, Shirley N. Weber, Ph.D., viewed 17 December 2025).