Return Flow

By Takagi Nobuko

Translated by William Wetherall

First posted June 1999

Last updated 7 August 2015

A version of this translation appeared in

Japanese Literature Today, Number 21, 1996, pages 22-31

Takagi Nobuko, born in 1946, received the Akutagawa Prize in 1984 for her novel Hikari idaku tomo yo.

"Return Flow" first appeared as "Kanryu" in Bungakukai, March 1994, pages 102-111.

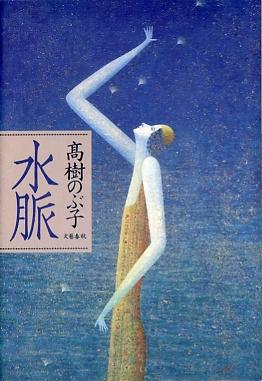

This translation is based on the version appearing in Suimyaku [Water veins] (Tokyo: Bungei Shunju, 1995, pages 125-143), a hard cover anthology of ten Takagi stories. The story has also been translated into French (1996).

In the depth of the night, when the phone rang twice, as though quietly murmuring, and the fax began to move in small bites, I already knew who the sender was, but to test my own hunch of whether I was right, I averted my eyes from the square machine and gazed toward the window for a while. I was about to retreat to the bedroom, and had I just stood up and left the room everything would have been moved to the next day. Why not do so? I thought for a moment, but when after all I became concerned and returned my eyes to the fax, only one line of handwriting had yet appeared on the white paper. My hunch had been right. Sumiko's familiar square writing came pushed out in two then three lines. Again I turned my eyes to the window. Reflected in the glass was the bookcase in the middle of the room, and the night sky was visible through the dark part of the bookcase. Though the glass was only a transparent pane, when I thought of both the bookcase in front of it and the distant night sky being on it, I was struck by how very strange it all was. I couldn't just stand there looking, though, so with resolve I redirected myself toward the fax. A single sheet of paper gently curled and rolled out. When I took it in my hand, while thinking that its casual, yet forceful impression was just like Sumiko, the warmth that had made its way through the machine felt to my fingers like human skin. And I felt as though Sumiko's face, blemish-free white cheeks and long-slit eyes that seemed to be wet, the thin nose that passed straight between them, lips that always exuded the color of blood even though she hadn't put on any lipstick, all these nicely configured like a doll, were on the paper, and before I pursued the writing, I turned to her face and heaved a sigh. I had never met Sumiko, and had not seen even a photograph, yet an image had firmly formed within me. And I imagined that, with a brooding face, she must be watching her own sentences, which were just now being sucked in by the machine. Until now a number of letters had come by fax from Sumiko, and so I had some idea what the contents of this one would be. She'd been afflicted with a serious renal failure since her mid teens, and had been receiving dialysis for nearly ten years. Her life, which was bound by dialysis three times a week, appeared to have snatched from her any opportunity for love and work, and she'd written about the circumstances of living a cramped life at her parents home, at times with a harsh spiteful feeling, at times as though seeking help. She once brightly wrote a fantasy, about if she were born again, but she was a woman who in any event enjoyed writing, and her keen words had the power to cause me, who had suffered from pyelitis when I was young, to write replies. I've sent, likewise by fax, a brief reply, once every two times she's written. But it appeared that her condition had worsened to the point that even hemodialysis couldn't save her, and for me such exchanges had become excruciating, the writing of repeated words of comfort had become trying, the words of encouragement had become empty, and recently I had no longer been sending replies. It all began when the woman, just because we had been in different grades at the same high school, sent me a one-page letter, to the fax I used for work when writing my novels. I thought that to call on the phone would probably disturb you, and so I've willfully presumed that you would allow me to send you these sentences unobtrusively, it said, yet the content of these sentences that had been willfully sent to me unobtrusively was serious, and the tone in which they were written, which seemed to mock this seriousness, was impressive, and I've gradually come to feel close to this woman. -- Good evening, Sensei [n 1]. Have you already gone to sleep? If you're still up, the stars are most beautiful, so please look at the sky for just a while. I'm in a most happy mood tonight. I stood up and went to the window, and when I looked through it, I noticed that the sky was glowing a hazy purple. But I couldn't see stars or anything. Sumiko's place must be where the atmosphere is clear. -- Making various designs in the night sky by connecting the shining dots with lines, I really love. The reason I am happy tonight is because an older man in the neighborhood brought me a monthly magazine. The older man likes me, and he concocts some business and comes here, and when leaving, he says Keep it up, Sumichan [n 1], and touches my shoulder and back. He insisted on asking if I'm still a virgin, and when I told him I was a virgin his eyes seemed about to cry. A who-cares sort of story, yes? The monthly magazine, though, had a wonderful article in it. An article with a discussion of peritoneal dialysis. It was a discussion between a doctor and a well-known person who has actually received peritoneal dialysis, and according to it, this is a new method which, instead of taking the blood out and washing it as in hemodialysis, you perform the dialysis with your own peritoneum. I'd heard of peritoneal dialysis before, but I didn't know what they actually do, and I had it in my head that it was probably impossible for a person who like me has had a long history of illness. But I've come to think that, just perhaps, I too might be saved by this method. Since I want Sensei to be glad, too, I'm now going to send you some materials. They are things that, because going to the hospital for dialysis has been very punishing on my body, a friend looked up and copied from some medical books in the library for me. If you are still going to be up and not sleep, please read the materials. I'll be in touch again when you will have finished reading them. The fax was already moving while I was reading. This time text and diagrams that I took to be copies from books were sent out to the sound of a minute vibration. Taking a total of three pages in hand, I was still confused. Had the first letter come after I had gone to bed, I would not be reading these materials tonight either, and Sumiko would have ended up facing a dark study and engaging in her various discourse alone. Sumiko too must be aware of this possibility, and she must be by the square machine, thinking that she might be sumo wrestling by herself. And so while thinking that there was really no need for me to keep her company, I began to feel as though I was being glared at by Sumiko from outside the window, and I had to start reading in order from the first page. It was a publication by the title of "The Latest in Treatment for Renal Failure", and to begin with conventional hemodialysis was explained in detail. Because I too had a history of kidney disease, I had general knowledge about hemodialysis. I knew that, in order to insert the needle used for dialysis you had to join an artery and vein, and that then you took out the blood and filtered it through an artificial semipermeable membrane and returned it to the inside of the body. Since you're bound to the hospital four or five hours every other day the burden is great, and, moreover, because the machine doesn't cover all the functions of a real kidney, you can't use one forever. Beside this explanation was an illustration of a patient tethered with two tubes to a dialyzer that looked like a big box. Following this, peritoneal dialysis was introduced as a new method. The peritoneum is a thin membrane enclosing what are called the viscera--the stomach, liver, intestines, kidneys and what not--and with numerous capillaries running through this membrane it has the quality of semipermeability. And because its overall area is also extensive, it seems that they are doing the procedure of dialysis using this membrane. They are doing the procedure performed by the semipermeable membrane outside the body using the peritoneum inside the body, and when looking along with this at the explanatory picture of the human body cut vertically in half, it's all very convincing. According to the picture, the viscera are flooded by infusing the dialysis solution from a small hole that has been opened by surgery, into the peritoneal cavity, which is the interior enclosed by the peritoneum. The peritoneum removes waste products, and introduces necessary substances in their place. Then all you do is once more take outside the body the dirty dialysis solution that results from this exchange. If you carry out this internal washing four times a day, they say you can get by without being confined to a hospital for long periods of time. Again the fax began to move. Because the timing was as though Sumiko was watching my every movement, I unwittingly turned and looked up at the night sky. I felt that Sumiko's eyes were shining in a dark mirror. If not this, then Sumiko may be fusing into the air of the room. -- Did you read the materials? Incredible, isn't it, doing dialysis with the membrane of the abdomen. I become invigorated just thinking about it. I mean, my peritoneum can do the same functions as a large dialyzer. So I too will go to the hospital, and receive peritoneal dialysis. My parents say that I should give up surgery that would open up a hole in my abdomen for this, that physically I'm not strong enough for it, but I will ask the doctor to do it. While I was writing tonight's first letter, my head suddenly became heavy, and I had to lie down for about five minutes. Maybe the urotoxins rose toward my head. But what do you think I saw afloat in my dark head? That Okinawan mangrove [n 3] tree that Sensei once wrote about in an essay, was spreading adrift, twisting and turning fully before my eyes! Too bad that though I clipped and kept that essay it's gone somewhere and I haven't found it. Is there really such a tree? I suppose there must be. A tree that sucks up seawater from its roots, and inside its body filters out the salt and discards it from its leaves, is my ideal. If there were such a plant, I would rather be a plant than a human being. I'd like to become an Okinawan mangrove and continue to live. Sensei, if you're still awake, would you tell me the story of that tree again? . . . My eyes were wide awake now, and I had this feeling that I would not be able to retreat back. Though I might try to retreat, Sumiko would probably come in pursuit. Be that as it may, with a feeling that I had been taught anew by Sumiko that the Okinawan mangrove was a plant with a dialysis mechanism, I quickly began searching for the materials with which at the time I had looked into the Okinawan mangrove. Various copies of articles, newspaper clippings, and other things that had been sent from the editor had been thrown into a drawer at the bottom of the bookcase. I began rummaging around from there. While moving my hands about, I wondered what sort of woman Sumiko was. The shape of her face that I had created in my own way was fixed in my mind, but since she had written nothing about her parents or her daily life I knew nothing about them. Her age, too, apart from it being mid twenties, was not clear. And now, only her blood vessels and blood and peritoneum floated into my eyes. Unable to find the materials in the drawer, I turned the pages of some illustrated books on plants, and searched for a collection of miniatures by the hand of an expert in a book called "A Pictorial Record of Plants of the South", but though "mangrove" was there, there was no item on "Okinawan mangrove". Since I did have a recollection of writing an essay on this unusual tree, somewhere there ought to be something that mentions this plant, I thought, and when this time I searched my scrapbook of essays, I found one I had written in a certain women's magazine some year and a half ago on the Okinawan mangrove with the title "A Strange Distilling Tree". Moreover, a clipping concerning this tree had been put between the same pages. I immediately sent Sumiko both the clipping and the essay. A document that appeared to be an academic society report entitled "Idiosyncrasies of the Okinawan mangrove", in addition to including several scientific names in Latin script, contained drawings of cells enlarged by a microscope. One after another of these were swallowed by the fax, and when I imagined them being spit out from Sumiko's fax, I had this feeling that the thick atmosphere of the night was a membrane separating me and Sumiko, and that now the drawings and text were going back and forth, passing through that soft membrane. Sumiko had told me about peritoneal dialysis, and I had sent her materials concerning the Okinawan mangrove, but on the way the two kinds of information had entwined as one, and after rolling up like a ball of potpourri, they had, with the impression of yarn again unraveling in the night air, flowed into one another's machines. I felt certain that Sumiko was straining her eyes and reading the received materials. "Okinawan mangrove". Family Verbenaceae [n 4], subfamily Avicennia marina [n 5], a constituent species of mangrove forests. Varieties differ with the researcher, but Chapman [n 6] reports six species from India to the Pacific and eastern Africa, three species in the Pacific Americas, three species in the Atlantic Americas, and one species in western Africa. A low or medium high evergreen tree; smooth, thin bark; roots that run horizontal through mud; sends numerous absorbent branches above the water. Leaves are in opposition, oval and horny, and their underside is pale green. There are some that accumulate the salt that is taken into their body in their leaves and dispose of the salt by dropping the leaves, and some that eliminate the salt from salt glands and salt pores on the leaves. -- Sensei, thanks. As I thought, you'd be awake and you've kept me company. I read the materials on Okinawan mangrove. What a wonderful plant. The inside of its body is most likely surrounded by a special membrane, and with this it must filter out the salt and get rid of it through the leaves. Do you know how much I now envy that plant? I'm thinking how nice it would be if there were such a membrane in my body too, and it could easily filter the mud and dirty water, and leave in my body only the pure and beautiful. But no, the peritoneum could play that role, couldn't it. In the essay Sensei wrote that it would be fun to be able to make a raft of tens, even hundreds of living Okinawan mangroves and set it adrift on the sea like a floating island, but I think it's possible to realize this. Because fresh water is distilled from the stems of the Okinawan mangrove, and salt can be taken from the leaves, we could live for several years, even tens of years right in the middle of the sea. Please tell me about any sequels to the essay. Won't you tell me in greater detail about the floating island? And please let me ride on that island. I want to be free both from the tubes and from the machines of dialysis. I want Sensei to save me. Please help me. I feel that I could become free if I would muster just a little courage, and tear and leap out of the membrane that is shutting me in . . . . Everyone says when this membrane is torn there is no life on the other side, that there is only death, but I don't think that's true. If life and death are divided by a thin membrane, there is no reason that one cannot go back and forth slipping through the membrane. Don't you think, Sensei, that just as you and I are now plying our hearts in the middle of the night, going back and forth through what appears to be a large barrier is possible? I promptly wrote a reply. -- I understand. How smart you are. It seems that the stars are very beautifully visible from your room. The sky outside my room is obscured by the lights of the city, but I'm going to strain my heart and search for the light of the stars. Won't you come outside? If you intently look beneath the stars, there ought to be a sea. I'll prepare the floating island of Okinawan mangroves. The preparation will take ten minutes. In ten minutes, let's meet beneath the brightest star. Then again a reply came from Sumiko in writing that seemed to dance. -- Great. But, Sensei, though selfish of me to say so, this past week, other than going to the hospital for dialysis, I haven't been out of bed even once. Hence my legs and back have weakened and I don't think I could possibly swim as far as beneath the stars. Won't you send the floating island to the seacoast near my house? The landmark is a sake brewery warehouse with a peaked roof, and the forest of pines that stretches out from it. The area of the warehouse is dark, but the fields that skirt the forest should appear to float up white even at night. I'll be waiting there. I'll wait even if it takes all night. For this reason it came about that I had to build an island of Okinawan mangroves in the depth of the night. I quickly reread the materials, and first considered the scale of the island. The bigger the better. I made it an oval island two kilometers by one kilometer. As for the Okinawan mangroves, I chose 20,000 of a species that is found in the southern part of Okinawa, and which has roots that push out widely and absorb water well. I intertwined their roots, which had spread into the sea, and arranged them in the shape of an island. To start with I made a space right in the middle for a residence, and though from there I had to cut a small path to the seacoast, this path I paved with tiles of limestone. By doing this, even in the dimmest light of the stars or the moon the small path, floating up white, would in many ways be convenient. From thereon things got difficult; I had to bundle several branches of the Okinawan mangroves, cut off their tips, and provide some mechanism for obtaining the fresh water. If all went well, it would produce fresh water by sucking up seawater in endless supply from the roots the trees pushed out into the sea, and if we could collect this water not only would there be drinking water but it would also be possible to make rice paddies and vegetable gardens; and were we to graft persimmon and fig and peach trees to the Okinawan mangroves, we'd make it without hungering for fruit. If possible, I wanted even mangoes and papayas. Since time had run out, I decided to push off in this condition as a first step, and go to greet Sumiko. Sumiko was standing right in the middle of the pine grove, looking like the silhouette of a pencil that had been stood up, but when she jumped on the small path on the island, she came to where I was, wavering as she walked on the white zone that floated up in the starlight. -- You came, at last. -- I came, Sensei. Thank you for making the terrific island for me. -- Rather than for Sumichan, perhaps I just wanted it. It's still incomplete, but let's build it together. While putting my arms around Sumiko's shoulders, I checked the shape of her face and felt relieved. She was beautiful like I had imagined, her eyes and nose were nicely configured like a doll, but in the moment of her bashful expression and smile their balance crumbled, and the double- tooth that was slightly lifting one side of her lips too was charming. -- First we've got to think about your dialysis mechanism, okay? I said, then she said, I've already thought about it enough. -- Look at my flank, there's a small hole there, see? I'm going to insert the branch of an Okinawan mangrove here like this and sleep. And look, there's a small hole here too, see? When she hitched up her long skirt, to the right side of where her golden pubic hair was sparkling, around her appendix, was something that looked like a long vertical incision, and it was a little wet. -- The water that comes in flows out here. The dialysis is completed while I'm sleeping. Nice, huh? -- That's nice and easy, yes. You've thought of a very clever thing. How about that, she's going to be tethered to an Okinawan mangrove, I thought. The Okinawan mangrove will purify the seawater it sucks from its roots and send it inside Sumiko's body. The waste products that permeate Sumiko's thin peritoneum will dissolve out in that water, and the dirty water will flow out the incision in the lower abdomen and return to the seawater. As long as she continues this every night, that is, as long as she becomes one body with the Okinawan mangrove, Sumiko will be able to continue living. It was time to promptly test it. -- Let's do it here, I said, taking Sumiko under a tree that seemed to be a good place to sleep, and to start with I tried lying down. Branches of the Okinawan mangroves entangled the night sky like the meshes of a net, and I realized that branches which had grown too long and things that were like aerial roots were drooping by the thousands. From tiny openings, the light of the stars poured down as fine powder. I lay Sumiko down, and I chose a branch that was soft and seemed as though it would drip water well and I cut off the tip, and I inserted it in the hole in her flank. Sumiko wrenched her body as though it had tickled. The skin of her throat and abdomen was white, and it seemed as though she'd respond sensitively no matter where she was touched, and I thought that if she's like this she may really be a virgin. -- Does it tickle? -- Yes . . . . Because it's the first time a thing like this has come into my body. But it feels very good. -- You should just stay this way and get a leisurely sleep. Everything's from tomorrow. I'm going to be by your side, so put your mind at ease. Sumiko finally fell into sleep. I too drowsily wandered in a dream, and at times I became concerned and checked Sumiko. I gently touched Sumiko's flank with my hand to see if the branch hadn't slipped from the hole. When, lifting the hem of her skirt, I checked her lower abdomen in the faint darkness, something wet and glistening was falling toward her inner thighs, straight from the incision in her skin. The liquid that wet her as it fell was coming up the root of the Okinawan mangrove and then going back into the sea. We continued to endeavor to complete the island from the following day. To begin with the two of us had to decide what was needed, but here some differences of opinion were born between me and Sumiko. Sumiko said that all that was necessary for living was already here, and maintained that all we had to make was perhaps a bed. I thought it would be nice if there were a desk and paper and pencils. But it was Sumiko's thinking that if we were to put a desk and paper and pencils on the island, we'd also want a phone and clock, and it would probably become more convenient for there to be electric appliances that ran on solar batteries too, so it would be better if there were nothing from the start. It seemed that because Sumiko had until this lived in a narrow sphere, she didn't know the convenience of various products and equipment. I was in a difficult position, but I decided to go along with Sumiko's thinking. Even the desk and paper and pencils, if we didn't have them we didn't have them, I felt we could still to go on living. To begin with we twisted and bent, and interwove, the aerial roots of an Okinawan mangrove, and built a house under a big tree. We considered rainy days, and as first step we covered the perimeters with foliage. We thought that if we just left it this way, the house would become even stronger with newly extended branches. That was our ideal house. The branches that grew into the house, we could used for Sumiko's dialysis. The other branches we could use as faucets providing fresh water. The problem was the place for elimination. In this, too, I eventually went along with Sumiko's thinking. She said that because the Okinawan mangrove sucks up seawater from the sea, and discards the excess as it is into the sea, it would be all right if people did so too. It turned out that we could squat everywhere on the island. Yet this was most agreeable, to the same extent that it was possible to eat anywhere on the island. I saw off, with a wistful, gentle feeling, the liquids that were discharged from the rents of my own body. The warm liquid, which had a bit of color, went flowing along the complexly interlaced roots of the Okinawan mangroves, and mixed with the seawater. Urination and defecation became pleasant times of the day, and I and Sumiko, we'd grin eye to eye, Shall we do it here today? and nod at each other, and squat. Since the roots of the Okinawan mangroves also served as fish shelters, we could grab fish by quickly extending our hands. So the island moved with the fish shelters. Everyday we went to the seacoast and looked around, but we were completely surrounded by the horizon, and we could not see the continent or other islands, nor were we able to spot the forms of any airplanes. This also made us happy. We felt the real sensation of having broken across the border of life, and come even further. I thought that if we continued to be swept along this way, we may well part from the sea and drift into space. Especially on nights when the stars looked close and beautiful, the stars would seem to penetrate beneath our island, far below the roots of the Okinawan mangroves, and lift up the entire island in mid air while bursting into sparks. Because the Okinawan mangrove not only filters the seawater but does photosynthesis, if all goes well we could go to a world where there is no oxygen. Day came and night came and day came and night came, and when this had repeated several times and again it was night, Sumiko, lying on a bed of leaves, muttered while she inserted the end of a small branch in the hole in her flank. -- I wondered whether life was something that had a beginning and end, but no, it only goes round and round. Even the water inside my body just goes round and round. Perhaps my body, too, may go around and return to its place of origin. -- Good night. Dream of going around and returning somewhere. So saying I kissed Sumiko. Whenever she falls into sleep, I do this to her. That night the moon was not out, and instead the stars jostled each other in the firmament. Unable to sleep, the stars being too bright, I watched Sumiko for a long time. At length I too seem to have slept. As was always the case, when I opened my eyes, Sumiko's body was stretched out long right by me. The surface of her body glittered in the light that fell like powder from the Milky Way around Pegasus and Cassiopeia, the Andromeda nebula and the Swan. Her chest and abdomen felt softly warm when I touched them, and I felt wistful as though caressing myself on some distant day. I also realized that by running my fingers over these areas this way, I would feel good, as though my body were melting, and if I left my fingers here, a burning ticklishness would spread all over my body from that point; and when I tried doing these things to Sumiko, she showed precisely those reactions, twisting her dream-possessed body and heaving a long sigh. Even among the several illnesses that from my teens to my twenties I had managed to slip out of, pyelitis was the most distressing. Three bouts of it, just counting the times I can remember. Sumiko may have embraced all the cast-off shells that I had desperately slipped out of. As I began thinking that, if when extending one life another did not become a victim, then surely the consistency of the universe might not balance, my feeling of having done something unpardonable to Sumiko intensified, and my vision became wet. Every time my fingers with prayer submerged into and floated up from the crevice of her soft body hair, from Sumiko's body, there spilled a gasping voice that well resembled mine. I thought that until this I may have distressed her, but that she was now okay. For I had built this island, and provided Sumiko with a place where she could live in peace, and made it so that she could travel anywhere she wanted. Should she tire of being connected to the Okinawan mangrove every night, she could become the Okinawan mangrove itself, with its superior permeable membrane, and live forever. When her eyes come open, I will tell Sumiko that there is this sort of method too . . . . When I imagined the thick trunk of an Okinawan mangrove with protrusions and hollows exactly like Sumiko's face and body, I unwittingly smiled at its cuteness. Notes

|