Tamura Taijiro's Shunpuden

The life of a Chosenese "spring girl" in wartime China

By William Wetherall

First drafted 23 December 2014

First posted 28 August 2015

Last updated 26 August 2023

Shunpuden Published editions • Tamura Taijirō • Wartime setting • Original story • GHQ/SCAP suppresses original • Kerkham on censorship • Sato on censorship

Carnality in action Tamura's dedications to Chosenese women • Flesh trumps race (and love conquers all)

"Would the Emperor call me a whore?" Harumi's "racial backhand" against Japanese who made a fool of her

Shunpuden films Akatsuki no dasso (1950) "Escape at Dawn" • Shunpuden (1965) "Story of a Prostitute"

Related article "Comfort women" or "sex slaves"? Nuanced history v. victimhood hysteria

Tamura Taijirō's "Shunpuden" (1947)How the life of a wartime "spring girl"

|

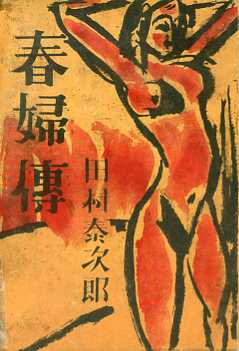

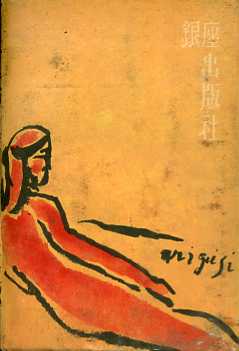

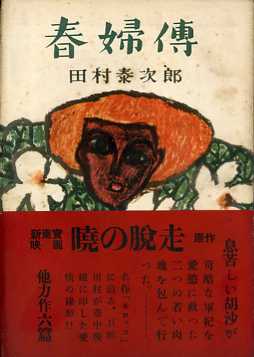

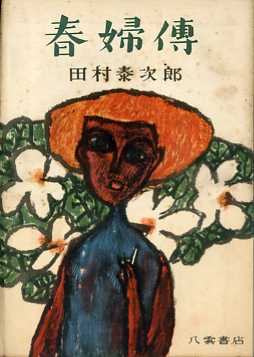

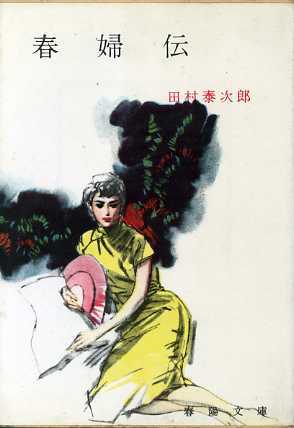

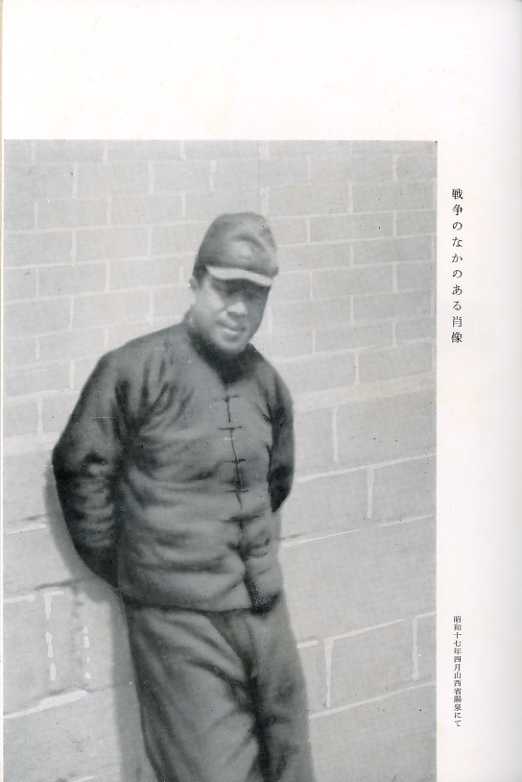

Published editions of "Shunpuden" in Yosha Bunko1947 Ginza Shuppansha editionōcæ║æūĤśY Tamura Taijirō 1949 Yakumo Shoten editionōcæ║æūĤśY Tamura Taijirō 1962 Shun'yōdō Shoten bunko editionōcæ║æūĤśY Tamura Taijirō 1965 Tōhōsha boxed editionōcæ║æūĤśY Tamura Taijirō The 1947 Ginza Shuppansha edition is a collection of 8 stories, beginning with the cover story, the novella Shunpuden (pages 1-69), by far the longest story. The 1949 Yakumo Shoten edition also had 8 stories, beginning with Shunpuden (pages 5-73), followed by the second story in the 1947 Ginza Shuppansha collection. All 6 other stories are different. The 1962 Shun'yōdō Shoten bunko edition includes 5 stories in addition to Shunpuden (pages 1-48), all of them different from the stories in the earlier anthologies. The 1965 Tōhōsha edition features Shunpuden (pages 5-57) with 7 stories not in the earlier editions, including Nikutai no akama (1946), the first of his "nikutai triology", the second being Nikutai no mon and the third Shunpuden, all written in 1946 immediately after Tamura returned to Japan from China. The frontispiece of this edition is captioned "A portrait during the war" which is said to show Tamura at Yangch'üan (Yangquan) in Shanhsi (Shanxi) province. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tamura Taijiro

Carnality in wartime China and postwar Japan

Tamura Taijirō (ōcæ║æūĤśY 1900-1983), born and raised in Kōchi prefecture, was educated in literature at Waseda University. He was active in literary circles, and was earning his living as a novelist and writer, when the conflict between Japan and China -- later called a war -- broke out in 1937.

In 1938 Tamura visited China, and the next year he visited Manchuria and northern China with other writers, who wrote about their observations and experiences in these areas. Many literary figures worked during the war years as journalists attached to Japanese military units.

Tamura himself was drafted in 1940 and spent the rest of the war in Shanhsi, the setting of Shunpuden. He was involved in combat and was also once captured. He had risen to the rank of sergeant by the time the war ended in 1945, but would not return to Occupied Japan until 1946.

Tamura's first novel, Nikutai no akuma or "Demons of flesh" (ō„æ╠é╠ł½¢é), about the carnality he witnessed in northern China, was serialized from September 1946 before being published as a pocket book. The story involves a relationship between a Japanese soldier and a Chinese women who had been captured as a communist guerrilla. He protects her from the brutality of other Japanese soldiers until she is returned to her village.

Tamura's most famous novel, Nikutai no mon or "Gate of flesh" (ō„æ╠é╠¢Õ), was published in May 1947. It immediately became a bestseller and was filmed in 1948. The novel has been the basis of four films and a TV drama as of this writing. The story involves a prostitution ring in postwar Japan in which the girls agree never to sleep with a man for free, and never to sleep with a GI.

Shunpuden, the topic of this article, also writen in 1946, and first published in 1947, is the third of Tamura's "nikutai triology".

Wartime setting of "Shunpuden"

The action in Shunpuden unfolds during the period when Japan was at war in China but not with China, at least from Japan's point of view. The Marco Polo Bridge incident north of Peiping on 7 July 1937 sparked battles between Japanese and Chinese forces in northern China. These battles took place in and around Peiping, as Peking had been renamed in 1928 when Chiang Kai-shek moved the capital of China to Nanking. The novel opens in the port town of Tientsin, where Japan had a small garrison as part of its extraterritorial concession there. By 30 July 1937, Tientsin had fallen to Japan, though for a while Japan continued to respect other foreign concessions.

The three women featured in Shunpuden had been working for a brothel in Tientsin, and were probably there from before the time Japanese troops took control of the port.

By the middle of August Japanese forces were embroiled in hostilities in southern China, and on 12 November they controlled Shanghai, from which they pursued Chinese forces fighting defensive battles in retreat up the Yangtze river. By 13 December the Chinese capital at Nanking had fallen, and by 25 October 1938, Japanese forces controlled Wuhan, halfway of the Yangtze between Shanghai and Chungking (Chongqing), where Chiang Kai-shek had set up his government in exile.

Japan never declared war on the Republic of China, and ROC did not declare war on Japan at that point. Japan ignored ROC's government in exile and worked instead with Chiang Kai-shek's former ally, now rival, Wang Ching-wei, to secure a constructive alliance between Japan and China.

On 30 March 1940, Japan sealed an agreement with Wang Ching-wei, who after ROC's government fled to Chungking had established his own nationalist government in the belief that China would suffer less by not fighting Japan. However, Japanese forces in the hinterlands of China continued to face mostly sporadic, though at times intense resistance from Chiang's nationalist forces and Mao Tse-tung's liberation army -- which had been fighting each other before Japan's incursions, but agreed to a truce in order to resist Japan.

The main action in Shunpuden takes place at a forward Japanese army base in Yu county (ß▒ī¦) in Shanhsi (Shanxi, Shansi) province (ÄRÉ╝Å╚). The county was at the front between Japanese units and guerilla bases. Japanese forces had invaded Shanhsi province shortly after the start of hostilities in northern China in the summer of 1937. Shanhsi was a stronghold of anti-Japanese resistance, and Japanese forces continued to carry out retaliatory actions against guerillas from Japan's bases in Shanhsi. Tamura spent most of the war years serving in the Imperial Army at bases in Shanhsi.

|

Yu county In 1995, four Chinese women from Yu County filed law suits against the Japanese government. They claimed they had been abducted and raped and made to work as comfort women by Japanese soldiers and demanded reparations and an apology. Three similar lawsuits followed. By 2011, all suits had been dismissed. Some of the judgments recognized the allegations but ruled that applicable laws did not permit judicial relief. The courts held that the women had no legal right to compensation, because Japan and the People's Republic of China (PRC), when normalizing their relationship in 1972, had agreed that all grievances were settled, and because of statutes of limitations.

|

Original story of "Shunpuden"

Shunpuden is set at a brothel attached to a Japanese Imperial Army unit in China. The original story features Harumi (Åtö³) from Heijō (ĢĮÜ▀ P'yŏngyang), and Yuriko (ĢSŹćÄq) and Sachiko (é│é┐Äq) from Heian Kokudō (ĢĮł└¢kō╣ P'yŏng'an Pukto), both parts of presentday DPRK. Harumi's name -- "spring beauty" -- virtually declares that she is the heroine.

The original version, which has never been published, contained a number of direct references to Chōsen, as well as the above place names. The revised published versions do not mention Chōsen, or the names of the women's home provinces, but other references make it clear that they are probably Chosenese.

|

The name Harumi is best known today as that of the singer Miyako Harumi (ōsé═éķé▌). She was born Ri Chunmi/Harumi (ŚøÅtö³) in 1948 the daughter of a Chosenese father and Interior mother, in Occupied Japan, where under Japanese and Allied Occupation Law they were Japanese. She and her family lost Japanese nationality in 1952 with other Chosenese and Taiwanese, and she naturalized in 1966 as Kitamura Harumi (¢kæ║Åtö³), thus adopting her mother's name. This was a year after Japan and the Republic of Korea normalized their relationship and signed a status agreement according to which Japan officially recognized ROK nationality. Most Chosenese in Japan eventually migrated to ROK nationality, but a few thousand -- including those born and raised in the prefectural Interior after Japan's surrender, and after the status agreement came into effect in 1966 -- remain Chonenese. The alien status of "Chosenese" in Japan today remains a legacy post-colonial status unrelated to either ROK or its rival for Chosenese loyalty, the Democratic People's Republic of Korea. For more about Miyako Harumi and other Chosenese and Korean public figures in Japan, see Public Figures in Popular Culture: Identity Problems of Minority Heroes in the Minorities section of Yosha Bunko for details. For more about "Chosenese" as a post-colonial legacy status, unrelated to ROK or DPRK, see Zaitokukai and the Japanese roots of Zainichiism: Special Permanent Residents as a caste of descendants of former Japanese, also in the Minorities section. |

The three girls had been sold to a brothel in the port town of Tientsin (ōVÆ├ Tianjin) by their parents in what was then a fairly widely practiced form of indent1ured servitude. Harumi and her lover were attempting to pay off her debt when he returns to the Interior and comes back to Tientsin with a wife.

Harumi and the other two girls then volunteer for work at a brothel being set up for an Imperial Japanese Army battalion encamped at a town in a neighboring inland province. The station is under military control, and Harumi and the other girls find themselves servicing lower ranking soldiers by day and officers by night. Harumi falls in love with Private Mikami Masayoshi, but has to tolerate forceful demands by his commanding officer, Aide-de-Camp (Lieutenant) Narita. A series of events results in Mikami being confined by Narita. Mikami asks Harumi to steal a grenade from Narita to help them escape, and when she realizes he plans to kill himself, she joins him in death. Yuriko and Sachiko cremate Harumi and scatter her ashes, not knowing her real name.

GHQ/SCAP suppresses original version of "Shunpuden"

The earliest version of Shunpuden that Tamura presented for public consumption appears in the galleys for the April 1947 inagural issue of the literary magazine Nihon shōsetsu. Tamura's story headed the list of several stories by various writers, some better known or more highly acclaimed than he.

The galleys of the April 1947 issue of the magazine were "submitted [for approval of publication] in January 1947 to the book section of the Press, Publications, and Broadcasting (PPB) of the Civil Censorship Detachment (CCD)" and hence Shunpuden had to have been written in 1946 (Kerkham 2001: 323-324). More specifically, they were submitted to "the Press-Publications unit of the Press, Publications and Broadcasting [sic = Broadcast] Division (PPB) of the Civil Censorship Detachment (CCD)" (Kerkham 2001: 335).

A copy of the suppressed galleys survives in the Gorden W. Prange Collection at the University of Maryland, and related documents. Prange (1910-1980) was a professor of history at the University of Maryland before the Pacific War and returned to the university after serving in the US Army from 1942-1951. He was stationed in Occupied Japan, during which time he served as General MacArthur's (SCAP's) Chief Historian. After returning to his professorial post, he wrote several books about the war, based on the primary sources he had collected, and the interviews conducted with Japanese military officers and others during his stay in Japan.

Civil Censorship Detachment (CCD) had a Communications Division which monitored mail, telegrams, and telephone communications, and a Press, Publications [Pictorial], and Broadcast Division that examined newspapers, books, movies, and plays. CCD was closely overseen by military intelligence officers in G-2 in the Government Section (GS), which was the military component of General Headquarters, Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (GHQ/SCAP). The Civil Communication Section (CCS) was responsible for helping rebuild Japan's radio, telephone, and telegraph infrastructure. The Civil Information and Education Section (CIE) was in charge of public information, education, religion, and other sociological and cultural matters. At the time, radio was the only electronic mass medium for disseminating public information and providing educational, entertainment, and cultural programs. The offices of both CCD and CIE were located in NHK's Tokyo headquarters building, which GHQ/SCAP had requisitioned for the purpose of using radio to help democratize Japan. NHK was then Japan's principal radio broadcaster. It would not begin its television services until 1955, three years after the end of the Allied Occupation.

Eleanor Kerkham on censorship of "Shunpuden"

From "HOLD" to "SUPPRESS"

The most valuable examinations of GHQ/SCAP's censorship of Shunpuden in English, based on an examination of original documents in the Gorden W. Prange Collection at the University of Maryland, have been made by Eleanor Kerkham, a now retired professor of Japanese literature at the University of Maryland.

Eleanor Kerkham

Censoring Tamura's "Biography of a Prostitute" (Shunpuden)

In Rachael Hutchinson, editor

Negotiating Censorship in Modern Japan

(Routledge Contemporary Japan Series)

Routledge, 2013

264 pages, hardcover

Pages 152-175

Eleanor Kerkham

Pleading for the Body: Tamura Taijiro's 1947 Korean Comfort Woman Story, Biography of a Prostitute

In Marlene J. Mayo and J. Thomas Rimer, editors, with H. Eleanor Kerkham

War, Occupation, and Creativity: Japan and East Asia, 1920-1960

Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2001

xiii, 405 pages, paperback

Pages 310-359

Kerkham reconstructs the series actions taken by GHQ/SCAP regarding the original galleys of Shunpuden. She reports that the "data sheet" attached to the galleys briefly described Shunpuden as follows (Kerkham 2001: 335).

. . . depicts the tragic story of a Korean Prostitute who committed suicide with a Japanese soldier at the China front. At the same time, it emphatically illustrates the corruption of the former Japanese army.

A two-page summary of the story attracted the attention of an officer who wrote -- "Leave this thing out! The mention of a Korean prostitute is dangerous, let alone the whole article." Kerkham points out his incorrect characterization of the "short novel" as an "article" -- suggesting that perhaps he misunderstood the intent of what he was reading.

The officer -- according to Kerkham -- struck out "hold" and wrote "SUPRESS" on the 1st page, then stamped "SUPRESS" on the 1st page and on each of the other pages. However, the image of the 1st page, which she includes in her article, shows "HOLD" block-printed in upper case, crossed out with "Sup" written in cursive lower case above it -- and, immediately above this, in the margin at the top of the page, a "SUPRESS" stamp.

The initial reason for the novella's suppression -- "incitement to violence and unrest". A later reason -- "criticism of Koreans". (Kirkman 2001: 335-336)

Kerkham expands on this reasoning as follows (Kerkham 2001: 340-341). Highlighting and boxed comments mine.

|

It happens that in 1947 occupied Japan, SCAP officials were indeed troubled by the brewing "Korean problem." Korean nationals, many of whom were forcibly brought to Japan as contract laborers during the 1930s and 40s, were demonstrating for their civil rights, seeking repatriation to Korea, or were at odds among themselves along Communist / non-Communist, South / North Korean lines. [Note 95] Although there is no indication that the problem of Korean "comfort women" was then an issue of concern to any of the parties involved -- Japanese, Korean, or American -- SCAP anxiety about "incitement to unrest" was undoubtedly real. [Note 96]. . . . Korean nationals Kerkham's "Koreans" in Japan were not "Korean nationals" but nationals of Japan. Under a dual status system of international and Japanese law, and SCAP's legal authority representing the Allied Powers as a multinational and transnational entity, Chosenese in Occupied Japan were "non-Japanese" only for purposes of repatriation, border control, and registration as aliens under the Alien Registration Order effective from 3 Mar 1947 -- shortly after Shunpuden was suppressed. SCAP, and the Japanese government under its own laws and SCAP's directives, regarded Koreans in Occupied Japan -- and otherwise treated them -- as possessing Japanese nationality. There was as yet no Korean state. Even after ROK and DRPK were founded in 1948, Chosenese in Japan formally remained Japanese nationals until losing Japan's nationality in 1952 when the terms of the San Francisco Peace Treaty came into effect. In Japan today, there are still some Chosenese. forcibly brought to Japan Practically all Chosenese who had come to the Interior as conscript laborers, some of them but not most forcibly brought, returned to the peninsula during the final months of the war and the early months of the Occupation. Practically all Chosenese who remained had migrated to the Interior on their own free will, and most had settled in the prefectures with families brought from the peninsula or begun after arriving in the prefectures. Not a few had been born in prefectures, and some were married to Japanese in Interior registers. seeking repatriation to Korea Practically all Koreans in Japan at the time had waived opportunities to return to the peninsula, either because they found life in the prefectures more to their liking, or because they thought economic, social, and political conditions in Occupied Japan were better than they were in the divided occupation zones on the peninsula. The repatriation program had ended in late 1946 and early 1947. The main "Korean problem" for SCAP authorities was the political divisiveness of Koreans in Japan, and the desire of many to be treated as "United Nations nationals" rather than as Japanese. SCAP refused to exempt Koreans in Japan from subjectivity to Japanese laws, as there were no legal grounds for treating them other than as Japanese pending treaty settlements. |

Kerham goes not speculate about whether Tamura himself intended his story as a comment about the "military role" in the plight of the women he depicts in his story. She suggests that SCAP -- because of the use of Japanese women for the "'comfort' and recreation of American [sic = Allied] forces in Japan" [Note 97] -- was perhaps "not at all eager to have the topic of militarized prostitution become a 'public issue'" and hence resorted to the censorship category of "criticism of an ally" as a "more legitimate sounding" reason to suppress the work.

Both reasons -- "incitement to violence and unrest" (bōryoku to fuon no kōdō no sendō ¢\Ś═éŲĢsēĖé╠Źsō«é╠É°ō«) and "criticism of Koreans [sic = Chosenese]" (Chōsenjin e no hihan Æ®æNÉléųé╠ößö╗) -- were listed on various "Key Logs" which had been issued by the end of 1946 to supplement the Code For Japanese Press issued on 21 September 1945 by the Civil Censorship Detachment of GHQ/SCAP's G-2 section.

Kerkham on publication of May 1947 Ginza Shuppansha collection

Kerkham makes the following observation, which suggests the extent to which opinion within GHQ/SCAP could vary -- as it did on other issues as well (Kerkham 2001: page 345, note 9).

9. Tamura Tajirō, Shunpuden (Tokyo: Ginza Shuppansha, May 1947), 1. The quote ["openly describing things which stagnated in my breast during the long war years"] is taken from the preface to a collection of stories featuring what appears to be a self-censored, "de-Koreanized" version of the short novel Shunpuden. This version did, to the later surprise of the magazine section, get past the Book Unit of the Press, Publications, and Broadcasting Division (PPB) of the Civil Censorship Detachment (CCD) and was published in May.

Hiroaki Sato on censorship of "Shunpuden"

"Why did they bother?

A more recent look at Shunpuden in English, by the New York based writer, translator, and critic Hiroaki Sato, was published in The Japan Times, to which he often contributes his takes on contempory and historical issues.

Hiroaki Sato

Redaction of a 'comfort woman' story

The Japan Times

The View From New York

3 November 2014

Sato made the following remark about the title assigned Shunpuden by GHQ/SCAP censors.

|

First, the title: It was translated "The Story of a Prostitute" for the Civil Censorship Detachment of the Civil Information and Education (CIE) Section of Gen. Douglas MacArthur's GHQ. A more faithful translation may be "The Life of an Alluring Woman," with the understanding that shunpu, "alluring woman," is one of the many words for prostitute. The distinction is important for the story. The heroine is an attractive, strong-willed woman known by her Japanese name, Harumi. In her sexual dealings with a dozen men a day, she still can develop a passion for someone she likes. So, she falls in love with a low-ranking soldier named Mikami, who is naive and timid. |

"Alluring" is Sato's way of representing the erotic and carnal nuances of "spring" (shun Åt) -- as used in expressions like "selling spring" (baishun öäÅt) and "spring picture" (shunga (Åtēµ), respectively the selling of one's body for sexual pleasure, and woodblock prints depicting sexual intercourse. Like many translators, Sato prefers to replace the perfectly good Japanese metaphor "spring" used in a romantic carnal context -- with "alluring", which replaces the metaphor with an interpretation or explanation.

"Shun" is here best translated "spring" in view of the fact that the protagonist's name is "Harumi" (Åtö³), meaning "spring beauty". The erotic associations of "spring" are clear enough in context. Whether "fu" or "pu" (Ģw) should be translated "woman" or "women" is a toss. I am inclined to prefer "women" because the story involves several such women, while mostly concerned with one of them -- though "woman" does underscore Harumi as the heroine.

Kerkahm glosses "shunpu" as follows (Kerkham 2001: 335).

Tamura's fictional vision is colored not only by his nikutai theory but also by a fantasy that he and other contemporary Japanese government officials and former military men have used to justify their own actions and attitudes -- that these women were "prostitutes" (the term "shunpu" in Tamura's title is literally "woman of spring" or "sex woman").

The characterizations of the "spring woman" in Tamura's story a "sex woman" and "prostitute" are Kerkham's, not Tamura's. In his longer dedication to Shunpuden in the May 1947 Ginza Shuppansha edition (see below), as well as in the narrative of his story, Tamura puts the girls who served in the "women's army" above the "prostitutes of Japan" who stayed in the rear to cavort with the officers and disparage the rank-and-file soldiers and the women who lived and died in the fighting.

Why all the fuss?

As Kerkham describes the revisions to the original story, both those that appear to be have been inspired by GHQ/SCAP's suppression, and those that seem to have been motived by self-censorship, the modifications involve mostly the elimination of direct references such as "Korea" and "Korean" -- by which she has to mean "Chōsen" and "Chosenese", since "Kankoku" and "Kankokujin" did not exist and Tamura wrote only of "Chōsen" and "Chōsenjin". Kerkham also cites expressions like "women who loved garlic and hot red peppers" -- and adds, "key terms such as race, personal names, or foods" among other things that might suggest Chōsen or Chosenese.

Sato, though, raises a question that Kerkham didn't ask (Sato 2014).

|

Among the altered words or expressions was "Korea" or "the Korean Peninsula," which was changed to "the land that is a corner contiguous to this Continent." But such deletions and alterations would not have duped any of the readers of the day. Then why did they bother? |

As I pointed out at the outset of this article, the title Shunpuden would probably have congered of recollections Shunkōden" to all 1947 readers familiar with Chosenese literature -- and that would have included quite a few Japanese in the prefectural Interior who were savvy about Chōsen and familiar with Chunkōden as a classical Chosenese romance. In fact, the story of Shunkōden was favorably dramatized in the Interior in 1938, and continued to be publicized by reprintings and even a bunko edition of Chō Kakuchū's play into the early 1940s. See Cho Kakuchu, Shunkoden, 1938, also in this Literature section, for details.

Carnality in action

Although Shunpuden does not use the word "nikutai" (ō„æ╠) -- "body" or "flesh" -- in its title, it counts as the 3rd work of Tamura's "nikutai triology" on the grounds that he clearly articulates his "nikutai doctrine" at the start of the story, as well as in the forward he wrote for the version first published in May 1947 by Ginza Shuppansha.

Tamura's dedications to Chosenese women

Tamara praised Chosenese women like those he portrayed in Shunpuden in at least two introductions he wrote for the story. I have transalted the entirety of the shorter edication he made to the original version of the story, which survives only in a copy of the galleys, and the first and most relevant part of his preface to the May 1947 Ginza Shuppansha edition. The 1949 and 1962 editions have no introductions, and the foreward to the 1965 edition does not especially concern the women in Shunpuden.

Tamura's dedication of "Shunpuden" in suppressed galleys version

| Tamura's dedication in supressed galleys version of Shunpuden | |

|

The Japanese text is my transcription of the dedication shown at the top of the 1st page of Tamura's Shunpuden as shown in an image of page 24 of the galleys in Kerkham 2001 (page 337, Figure 29). The structural translation opposing the Japanese text is mine. Note that the parenthetic (ŹņÄę) (Author) at the end has been struck out on the galleys, presumably by the editors of the magazine that had positioned Tamura's story first among several short stories in magazine. The sources of Kerkham's and Sato's versions are shown below (see source details above). All [bracketed remarks] are mine, except in Kerkham's translations, where they are hers. All highlighting and related comments are mine. |

|

Original text (Tamura Taijirō)é▒é╠łĻĢęéüAÉĒæłŖįæÕŚżē£Æné╔özÆué╣éńéĻéĮō·¢{īRē║ŗēĢ║ÄméĮé┐łįł└é╠éĮé▀üAō·¢{ÅŚÉ½é¬ŗ░Ģ|éŲńjĢÄéŲé┼ŗ▀é├é®éżéŲéĄé╚é®é┬éĮéĀéńéõéķŹ┼æOɳé╔ÆÉgéĄüAé╗é╠¹“ÅtéŲō„ķōéŲé¢Sé┌éĄŗÄé┬éĮØ╔õ▌é╠Æ®æN¢║ÄqīRé╔é│é│é«üB |

Structural translation (William Wetherall)I dedicate this story to the tens of thousands of Chōsen[ese] girls' [women's] army [members] who, to comfort the lower-ranking Japan[ese] Army soldiers who had been deployed in the hinterlands of the continent during the war, offered themselves to every foremost frontline [forefront] that Japan[ese] women out of fear and contempt would not approach, and ruined their youth and bodies [flesh]. |

Eleanor Kerkham (2001: 311)I dedicate this story to the tens of thousands of Korean women warriors [Chōsen joshigun] who, to comfort ordinary Japanese soldiers deployed to the Asian mainland during the war, risked their lives on remote battlefields where Japanese women feared and distained to go, thereby losing their youths and their bodies [nikutai]. |

Hiroaki Sato (2014)This piece is dedicated to the tens of thousand of Korean Daughters who volunteered to every battlefront, which Japanese women would not approach with fear and contempt, in order to comfort the lowest-ranking soldiers of the Japanese Army deployed to the interiors of the Continent during the war, and who thereby destroyed their youth and bodies. |

Comments on my translationhinterland is my preference for "okuchi" (ē£Æn), which is metaphorically a "back land" in the sense of a place that is deeper in the more remote bowels of coutry as seen from its capital, larger cities, or coastal ports. The term "naichi" (ōÓÆn) is metaphorically an "interior land" of a country viewed from its coasts, ports, or peripheral territories, or outlying islands. In Imperial Japan, however, "Naichi" (ōÓÆn) was also the formal name for the prefectural "Interior" jurisdiction of Japan, as distinct from Chōsen, Taiwan, and Karafuto (which joined the Interior as a prefecture in 1943). Furthermore, Chōsen, Taiwan, and Karafuto (before it joined the Interior) were informally regarded as "gaichi" or "exterior lands" relative to the Interior, although they were included with the Interior within "Japan" as a sovereign dominion, as distinct from territories that were legally under Japan's control and jurisdiction hence part of Japan's legal empire but not part of its sovereign empire. Tamura associates the soldiers (heitai Ģ║æÓ), the women (josei ÅŚÉ½), and the "girls' [women's] army (joshi gun ¢║ÄqīR) with "Japan" (ō·¢{) and "Chōsen" (Æ®æN). If pressed to clarify himself, he might say that he meant they were "Japanese" (Nihonjin ō·¢{Él) and "Chosenese" (Chōsenjin Æ®æNÉl) as "people" (jin Él), which the English "-ese" suffix is apt to imply. If further pressed, he might say that he meant "people" in a racial rather than civil sense, though at the time Chōsen was an integral part of Japan and Chosenese were Japanese by civil nationality. Japanese law has never coded "race" or "ethnicity" and hence "-jin" (-Él "-person, -ese") suffixes in Japanese legal parlance denote only a civil status based on the territorial affifiliation of a person's domicile or household (family) register. In English-speaking circles, including those in which Kerkham and Sato were writing, people habitually use "Korea" as a generic term for the peninsula and/or a government on the peninsula, and "Korean" as the attributive form of "Korea" or noun meaning the people of Korea -- even during periods when "Korea" and "Koreans" did not exist. The Allied Powers also did this, though occassionally Allied documents stated "Korea (Chosen)" as though to remind people what "Korea" actually meant in the legal world. Today these distinctions are blurred or entirely lost, which makes it difficult to civil status issues then and even now -- and difficuult to talk about people who consider themselves "Kankokujin" (Korean) or (not and) "Chōsenjin" (Chosenese) or (not and) "Korian" (Chorean). offer oneself (teishin suru ÆÉgéĘéķ) means simply to contribute one's body (and soul) to a cause, to step forward on one's own volition and throw oneself into doing something -- i.e., to volunteer one's labor -- never mind that there may be considerable social pressure to do so, and that not doing so may bring about severe criticism if not also social ostracization. Kerkham's "risk one's life" (see below) puts an interpretive spin on Tamura's expression rather than leave its meaning to the reader to consider in the larger context of the statement -- volunteering for work a battle zone. Elsewhere, too, she at times "over translates" (and sometimes "under translates") Tamura's phrases. Comments on Kerkham's translationKerkham renders "Chōsen joshigun" in the deleted introduction as "Korean women warriors" -- which technically overtranslates "Korea women soldiers" (Chōsen women soldiers) if not "Korea women's army" (without seeing the original I cannot determine whether the numbers are counts of individuals or descriptions of the size of the military group they comprise. Kerkham later, intentionally (and I think playfully), morphs "women warriors" into "Amazons" in this comment (Kerkham 2001: 315). In the novel Shunpuden, Tamura depicts his three Korean "Amazon soldiers" as having been sold to their parents to what seems to be a privately owned brothel for Japanese army officers and civilians in the city of Tianjin, Hebei Province. [Note 31] Comments on Sato's translationSato makes a case for "daughters" as a translation of "joshigun" (ÅŚÄqīR), which he points out is "niangzijun" in Chinese and originally "referred to the army of women that Tang Emperor Liyuan's daughter Gongzhu is reputed to have raised to help her father." However, here the term "joshi" (ÅŚÄq) simply modifies "army" (gun īR) without pretensions alluding to classical literature. It was used attributively in all manner of expressions to mean simply "girl" or "female" or "women's" -- as it does here. |

|

Tamura's dedication of "Shunpuden" in May 1947 Ginza Shuppansha edition

| Tamura's dedication in May 1947 Ginza Shuppansha edition of Shunpuden | |

|

The Japanese text is my transcription of the 1st paragraph of Tamura's 2-page foreword (jo Åś) to the October 1947 Ginza Shuppansha edition of Shunpuden (Foreword, 1). The structural translation opposing the Japanese text is mine. The translation following these panels is Kerkham's (Kerkham 2001: 340). The [bracketed titles] in Kerkham's version are hers. All highlighting, other [bracketed remarks], underscoring, and comments are mine. |

|

Original text (Tamura Taijirō)üuÅtĢwÖBüvé═ī┤ŹeŚpÄåĢS¢ćé╠Åæē║饏ņĢié┼éĀéķüBØDÓźé╠ŖįüAæÕŚżē£Æné╔özÆué╣éńéĻéĮÄäéĮé┐ē║ŗēĢ║ÄméĮé┐éŲłĻÅÅé╔üAō·¢{īRé╠ŽŹZéŌé╗é╠ÅŅĢwéĮé┐é┼éĀéķīŃĢ¹é╠ō·¢{é╠Å®ĢwéĮé┐é®éńńjĢ╠é│éĻé╚é¬éńüAÅeē╬é╠é╚é®é╔ÉČé½üAé╗é╠¹“ÅtéŲō„ķōé¢Sé┌éĄŗÄé┬éĮ¢║ÄqīRé═éŪéĻéĮé» [sic ~ü@éŪéĻéŠé»] æĮØ╔é╔é╠é┌éķéŠéńéżüBō·¢{é╠ÅŚéĮé┐é═æOɳé╔éÓÅoé─śęéńéĻé╚éóéŁé╣é╔üAŽŹZéŲé«éķé╔é╚é┬é─üAÄäéĮé┐ē║ŗēĢ║ÄméńjĢ╠éĄéĮüBÄäé═ö▐ÅŚéĮé┐¢║ÄqīRéųé╠ŗāé½éĮéóéŌéżé╚ĢńÅŅéŲüAō·¢{é╠ÅŚéĮé┐éųé╠Ģ£ÅQōIé╚¤åÄØé┼é▒éĻéÅæéóéĮüBüuō„ķōé╠ł½¢éüvüAüuō„ķōé╠¢ÕüvéŲō»éČéŁüAÆĘéóØDÅĻÉČŖłé╠éĀéąéŠé╔üAÄ®Ģ¬é╠ŗ╣é╠é╚é®é╔ēTÉŽéĄéĮéÓé╠ééįé┐é▄é»éĮéÓé╠éŠüBé▒é╠ŹņĢié╠Åośę×─é”é╔é┬éóé─é═üAÉ│Æ╝é╚éŲé▒éļé▄éŠÄäÄ®ÉgéµéŁéĒé®éńé╚éóüBéĮéŠÄäé═üAÄ®Ģ¬é╠ō„ķōé╠é╚é®é╔üAīīéŲÅ╔ēīé╠ō§éąé┼ÓÄéĄé®éĮé▀éńéĻéĮüBŚØŗ³éÆ┤é”éĮö▀Æ╔é╠é®éĮé▄éĶé╠éŌéżé╚éÓé╠é¬éĀéķé╠éüAé═é┬é½éĶéŲŖ┤éČé─éŅéķüBÄäé═¢▓Æåé┼üAé╗éĻéĢ\ī╗éĄéµéżéŲÄÄé▌éĮé╔éĘé¼é╚éóüB |

Structural translation (William Wetherall)Shunpuden is a work of 100-pages of manuscript paper which [I] wrote [as a whole for publication without serialization]. As for the [women in the] girls' army -- who, during the war, together with us lower-ranking soldiers who were posted in the hinterland of the continent -- while being disparaged by the officers of the Japanese Army and the prostitutes of Japan in the rear who were their paramours, lived in the middle of gunfire, and destroyed their youths and bodies -- how large a number would they climb to? The women of Japan, despite not coming to the front, having become conspirators with the officers, desparaged us lower-ranking soldiers. I wrote this [story] with an affection toward [the] women [of the] girls' army such as [so strong] that I want to weep, and revengeful feelings toward the women of Japan. Like Nikutai no akuma [Demons of flesh] and Nikutai no mon [Gate of flesh], [Shunpuden is something in which I vented things that had pented up in my chest during [my] long battlefield life. As for the making of this work [as for how I managed to write this story], frankly I myself don't well understand. [It's] just [that] I, in my own body [flesh], was fumigated and hardened in [by] the smell of blood and nitrate smoke [explosives]. I clearly feel that [in my body (flesh)] there is somehing like a lump of grief [sorrow, pain] that transcends reason [logic]. I, [as] in a dream [absorbed in these feelings], merely tried to express them. |

Eleanor Kerkham's translationDuring the war there were undoubtedly a great many women who sacrificed their youths and their bodies, while held in contempt by Japanese officers and the Japanese prostitutes serving as their war wives in the rear guard. They lived within the range of gunfire along with us lower-ranked soldiers stationed in the Asian Mainland. The Japanese women, assuming they must not go out to the battlefields, conspired with commissioned officers and despised ordinary, lower-ranked soldiers. I have written this story with a heart-wrenching longing toward those frontline women and with feelings of disdain toward the Japanese women. This is a work in which, just as in my Nikutai no akuma [Devil of the Flesh] and Nikutai no mon [Gateway to the Body], I have openly described things that stagnated in my breast during the long war years. To tell the truth, I cannot yet judge its literary quality. I have simply felt, with a clarity deep within my flesh and bones, that there was within me a dark, inchoate cloud of grief that smoldered unbearably with the scent of blood and gunpowder smoke. Dazed, like a man lost in a dream, I knew that I must try top put my feelings into words. [Note 94] Note 94 Tamura Taijirō, Shunpuden (Ginza Shuppansha, May 1947), preface, 1. |

|

Comments on Kerkham's translationKerkham's version is a very loose and embellished adaptation, not a translation. She seems to have no respect for Tamura's powerful phrasing and metaphors. Nothing he writes requires the paraphrasing, explanation, and commentary she swaps for his straight, simple, and perfectly pitched diction. Translation is not about language -- not about Japanese and English -- but about story and narrative. Translation requires accepting that the author is the story teller, and recognizing that the reader is smart enough to understand and appreciate the way the author tells the story. Comments on my translationwomen of Japan" Tamura does not call the prostitues who cavorted with the officers "Japanese women" but "women of Japan" -- which are obviously the "prostitutes of Japan" who are "paramours of the officers". This implies that the girls in the "women's army" are not "of Japan". In the original verious of Shunpuden, they were "of Chōsen" (Chōsen no Æ®æNé╠). guru I have underscored guru (é«éķ) because Tamura stressed this expression with dot marks (bōten ¢Tō_) beside the hiragana. Nikutai no akuma was first collected in an anthology of Tamura's stories published in April 1947. This was reprinted the following year when another published brought out another anthology that featured the novella as its cover story. I would guess that Tamura took the title of from the Japanese translation of Le Diable au corps (The Devil in the Flesh), the 1923 novel by Raymond Radiguet that set in the Great War. The first of several Japanese translations of Radiguet's novel was published as Nikutai no akuma (ō„æ╠é╠ł½¢é) in 1930. A second translation as Oni ni tsukarete (¢éé╔£▀é®éĻé─) [Possessed by the devil] came out in 1946, the year Tamura wrote his novella. A third translation bearing the compound title Nikutai no akuma: Oni in tsukarete (ō„æ╠é╠ł½¢éüF¢éé╔£▀é®éĻé─) [The devil of flesh: Possessed by a demon] came out in 1952, when the first of several movie versions of the novel, a 1947 French production, was released in Japan. At least two other translations have since been published, both as Nikutai no akuma. nikutai Metaphorically, all appearances of "nikutai" (ō„æ╠) in Tamura's stories should probably be consistently translated "flesh". He uses other words, such as "shintai" (Égæ╠), for body. The "body" is a corporal object, a vessel for the "flesh" that incarnates the body's carnal spirit as it were. Note that everything Tamura says about his own state of mind reflects his characterization of the "carnal" condition of the women's lives. His body, too, is driven by the emotions that originate and fester in his very flesh. |

|

Flesh trumps race (and love conquers all)If likeable like, if hateful hate, and no regretsThe human condition of the women in "Shunpuden" is essentially one of "carnality" -- meaning that every thing they do is determined by the "will" of their "bodies" or "flesh" -- depending on how one wishes to translate "nikutai" (ō„æ╠). As I stated above, I characterize Tamura's "nikutai-ron" (ō„æ╠ś_) as "nikutai doctrine". If pressed to fully anglicize the expression, I would render it "doctine of carnality". If pushed for an explanatory translation, I would go with "carnal determinism". Three pages into Shunpuden, following fast and dramatic establishing scenes, comes a long paragraph that essentially defines the geographical and socio-economic origins of the three women featured in the story. The paragraph also articulates Tamura's doctrine of carnality, according to which his characters live through the wills of their bodies or flesh. In her 2001 article on Shunpuden, Eleanor Kerkham translates the entire paragraph as it appeared in the galleys submitted to GHQ/SCAP for its approval in early 1947, with her notes and commentary. However, she divides her translation into two parts, one earlier and the other later in her article. And elsewhere in her article she comments on matters related to the original and revised versions of this paragraph. In the following table, I have first shown Kirkham's translation of the original version (left), followed by my transcription (center) and my structural translation (right) of the revised version of the paragraph.

|

|||||||||||||||||||

"Would the Emperor call me a whore?"Harumi's "racial backhand" against Japanese who made a fool of herKerhkam takes too many liberties in some of her summaries of Tamura's narrative. Rather than show readers what Tamura writes, let them participate in his drama without her running commentary, and then step back and ask what he was doing in the story -- she front loads her presentation with her own story, in the course of which she lifts things out of Tamura's story to suit her own viewpoint -- and not infrequently she garbles the details. Her overview of Harumi's comments about the emperor is a good example of what she does (Kerkham 2001: pages 318-319 and notes, all [bracketed remarks] and highlighting mine).

Tamura tells the story rather differently. Harumi quickly becomes very popular and everyone wants to play (asobu ŚVéį) with her. The lieutenant who barges in to her room in the following scene has only heard of her by reputation, but is determined to have his turn, even if it means pulling rank and breaking in line. Tamura uses "asobu" (ŚVéį) in its totally conventional sense of "play" or "hang out" or "have fun" -- whether kids with toys in room or on a swing in a park, or high school students at a fastfood shop after school, or an office girl in bed with her married supervisor at a love hotel. My structural approach is to translated the word just "play" and leave its nuances to the reader. The word "yūjo" (ŚVÅŚ) is an old term in Japanese for "pleasure girl" while "playgirl" is "pureigaaru" (āvāīāCāKü[āŗ). Midnight has come on the 5th night and someone pounds on Harumi's door so hard it seems it might break. The sergeant major, who was there for the night, is sleeping in her bed. She asks who's calling and says she has a guest. "I don't care, open up", the caller says and starts kicking the door. She can see his eyes peering through a space between the door and the frame. He kicks the door harder, calls her a fool, and worrying he'll break the door, she releases the catch and opens it herself. Harumi tries to block the door, but the tall officer pushes her aside and barges in. It was the lieutenant. He sees the man on Harumi's bed and orders him to get up. The sergeant, pretending he was asleep, opens his eyes and lifts his head from the pillow. The lieutenant recognizes him, and knowing he'd been permitted to stay the night, says, "You've already played, right? So change with me (mō, asondan daro, na, kawatte kure yo éÓéżüAŚVé±éŠé±éŠéļüAé╚üAé®éĒé┬é─éŁéĻéµ). The sergeant's acknowledgment of the lieutenant's request was weak, but seeming resigned about it, he stands to leave. "Why are you leaving? You can't leave," Harumi says, taking his arm, while glaring at the lieutenant. "You leave (anta wa kaere yo éĀé±éĮé═é®é”éĻéµ)," she says to the lieutenant. "I'm not playing with you." The narrator remarks that Harumi doesn't care if she's killed, she's not going to take the officer as a partner. (1947: 18-21, 1949: 22-24). The confrontation escalates like this (1947: 21, 1949: 24-25).

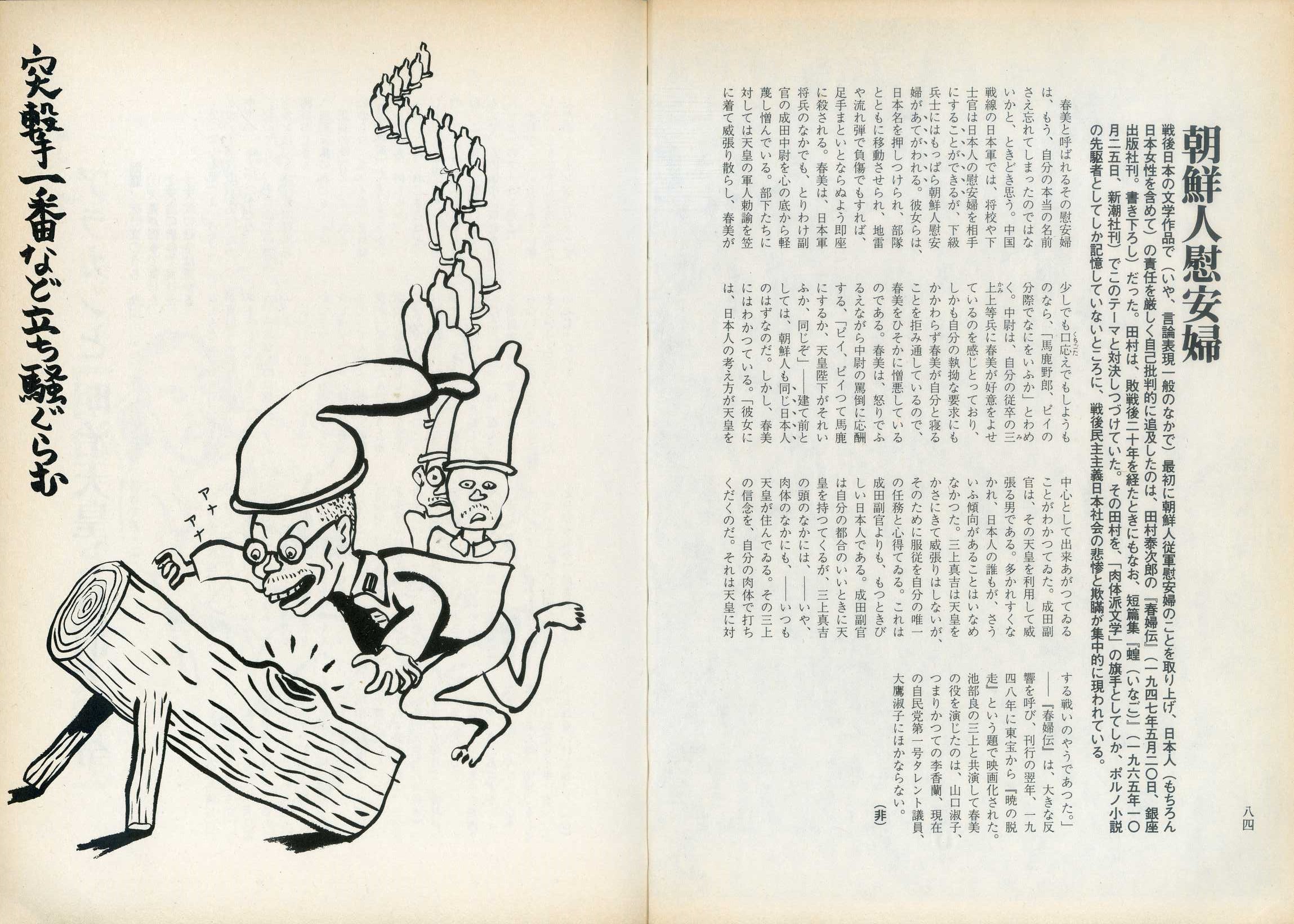

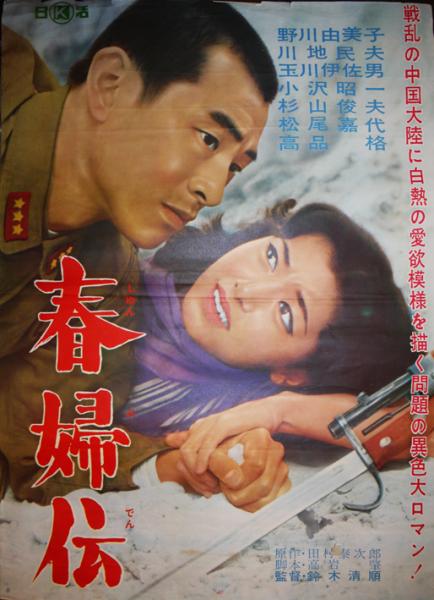

Shunpuden filmsThe 1st movie version, made in 1949 and released in 1950 by Shin Tōhō (ÉVōīĢ¾), corrupted the original story, beginning with its title, "Akatsuki no dassō" (ŗ┼é╠ÆEæ¢), or "Escape at Dawn" as it is generally known in English. The film was directed by Taniguchi Senkichi (ÆJī¹Éńŗg 1912-2007) from a script he wrote with the help of Kurosawa Akira (ŹĢÓV¢Š 1910-1998). After squabbling over how to handle the Chosenese elements that remained in the novel, and the manner in which the lovers died, the film turned Tamura's story into a very different kind of drama. The 2nd film adaptation, made and released in 1965 by Nikkatsu (ō·Ŗł) and directed by Suzuki Seijun (Śķ¢žÉ┤Åć b1923), attempted to return Tamura's story to its novelistic roots, but ended up corrupting it in different ways -- again without its original Chosenese elements.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||